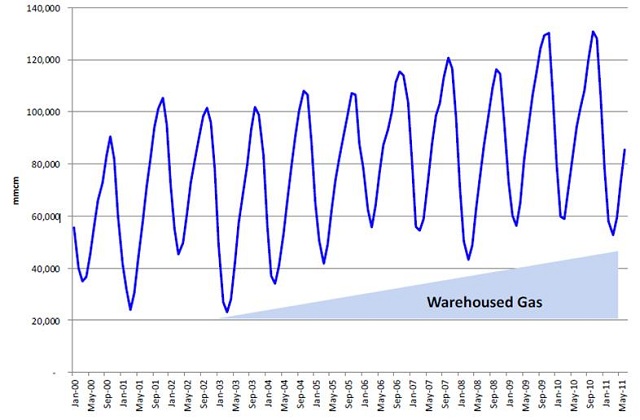

As the European gas market matures, so does the depth and sophistication of flexibility services available. Swing and storage products form the foundation of the evolving market for gas flexibility in Europe. While these products are not new in the European market, improvements in hub liquidity have driven a rapid shift towards the valuation, optimisation and hedging of product flexibility against hub price signals.

The time dependent flexibility (or optionality) embedded in gas storage and swing contracts is one of the more complex analytical challenges in energy markets. Quantitative analysts and academics have spent the last 15 years deriving a variety of techniques to tackle the issues of valuing, optimising and hedging gas asset flexibility. These approaches have become increasingly standardised over the last few years, resulting in a shift in focus to application of models as the key differentiator. The focus here is on the input parameters being used (e.g. pricing model assumptions).

In this article we summarise the relationship between swing and storage and set out and compare the three most widely applied approaches for coming to grips with gas flexibility value and optimisation. Some asset managers or analysts may have a preference for one approach over another. But in our view the most important factors are understanding the strengths and pitfalls of each approach and ensuring that the methodology is applied in pragmatic way which is consistent with the actual management of the asset or contract.

The equivalence of gas storage and swing

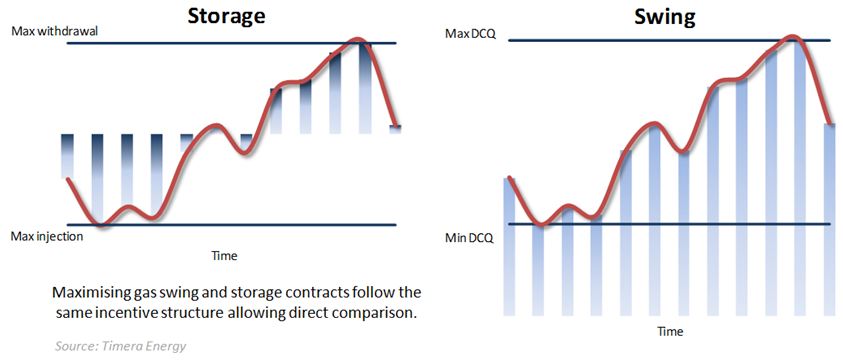

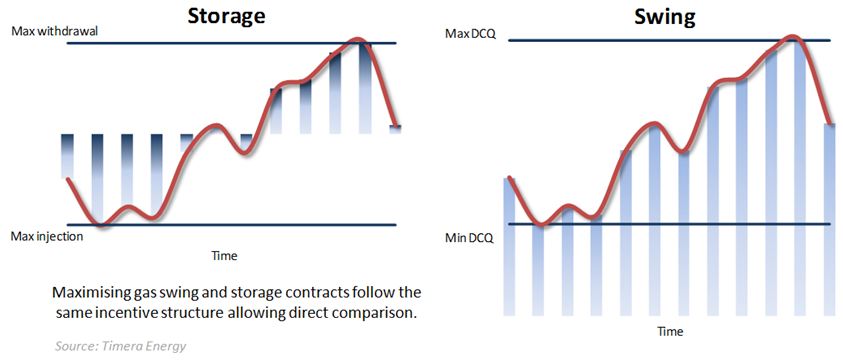

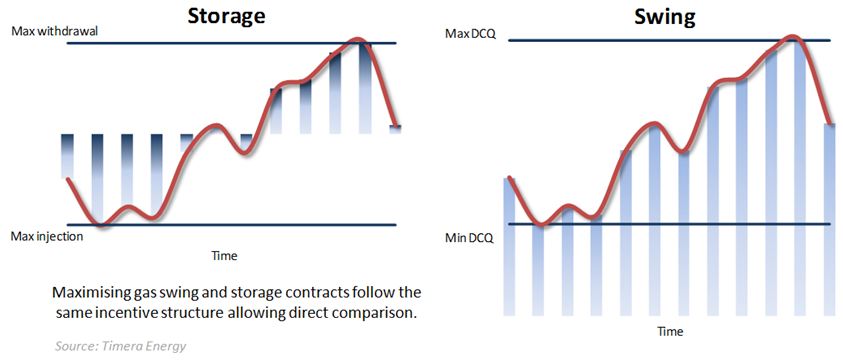

Intuitively there are strong similarities in the nature of the optionality embedded in gas storage and swing contracts, as both require daily (or even sub daily) volume decisions that will have a bearing on what can be done in future periods. That is both have time dependent optionality.

However, the precise equivalence between swing and storage is not always immediately obvious. To clarify this it is useful to look at an example. A simple fixed price annual swing contract can be viewed as a special case of a gas storage contract with the following attributes:

- Starts with a full inventory (up to the maximum annual take)

- Has no injection rights (i.e. inventory can only be drawn down)

- The withdrawal capacity is equal to the daily swing

- The withdrawal fee is equal to the contract price (i.e. what is paid for each unit withdrawn)

- At the end of the year the inventory can be between zero and the maximum annual contract quantity less the ‘take or pay’ quantity

When the contract is viewed in these terms it becomes clearer why the embedded optionality is essentially equivalent, i.e. why swing can be viewed as a less complex storage problem. This is illustrated in Diagram 1. This means the same underlying techniques can be used for valuation and optimisation of the asset flexibility.

Diagram 1: The equivalence of storage and swing

Note, that swing contracts often have complicating features requiring extensions to the general case described above. These features can range from the very simple (such as the inclusion of a baseload volume tranche) to the very complex (such as carry forward and make-up provisions or indexed contract prices).

Three broad categories of valuation methodologies

There are three broad categories of methodology commonly used to quantify the flexibility (or extrinsic) value of gas storage and swing.

Rolling intrinsic

This is the most transparent and intuitive methodology and as a result it often favoured by asset managers and traders. Flexibility value is managed by locking in observable forward curve spreads and then making (risk free) adjustments to hedge positions as prices move, in order to monetise market volatility. Planned injection and withdrawal decisions are adjusted to add additional margin.

A simulation based methodology can be implemented based on the following logic for each simulation:

|

t = 0

|

Optimise the storage facility against the currently observed forward curve and execute hedges to lock in intrinsic value.

|

|

t = 1 to T

|

Simulate the movement in the forward curve and re-optimise storage contract.

Calculate the value of unwinding existing hedges and placing on new hedges against re-optimised profile and execute profitable hedge adjustments.

|

The key points here are that at any point in time the hedge position matches the planned injection and withdrawal profile and the outturn margin will always be higher than the initial intrinsic hedge as adjustments are only made if it is profitable to do so.

Constrained basket of spreads

This methodology considers a storage contract as a series of time spread options to swap gas from one period (injection) to another in the future (withdrawal). The volume of available spread options is constrained by the physical characteristics (injection, withdrawal and space) of the contract or facility. The structure of the methodology is quite straightforward involving two steps:

- Calculate a matrix of the spread option values of the different time periods (e.g. month). There are a range of spread option pricing models that can be used (e.g. Kirk or Margrabe) but all are likely to require volatility for each bucket and the corresponding cross maturity correlation.

- Select the value maximising volume (“basket”) of spreads that is consistent with the injection, withdrawal and space constraints. This is typically based in a simple linear or mixed integer linear program.

The simple structure can be integrated into a simulation to capture how the structure of the spread options cascade in line with tradable products and how the facility is optimised in the prompt. Note, that in some cases more value can be created by allowing the model to trade linear products as well by effectively increasing the feasible volume of the spreads (e.g. for a given period a will allow the withdrawal legs of spreads can be offset against fixed injections increasing the overall available volume).

Optimal

There are several techniques in this category that are typically grouped together due to the similarity in their structure and underlying algorithms:

- Trinomial Trees

- Stochastic Dynamic Programming (SDP)

- Least Squares Monte Carlo (LSMC)

The common theme across the methodologies is that the optimisation decisions are in the spot (and as such, only require spot price models). In simple terms they are considered optimal as the decisions are aligned to the actual decision faced by the asset operator. That is, how much to inject and withdraw on a daily basis given imperfect foresight of future market prices but knowledge of spot price behaviour. For example: prices are volatile, if the spot price is high today it is also likely to be high tomorrow, prices are likely to drift back to an equilibrium level.

All three methodologies define a state space based on the time and inventory level. Then starting at ‘end of period’, use backwards recursion to determine the value maximising action (inject, withdraw and do nothing) for each state given consideration of spot price uncertainty. The methodologies differ in their treatment of spot price uncertainty and how it is incorporated into the calculation of the state transition value.

A comparison of the methodologies

The key advantages of the different methodologies are presented in the table below:

|

Advantages

|

Disadvantages

|

|

Rolling intrinsic

|

- Simple and transparent which promotes trust in results

- Consistent with the way many companies hedge and optimise flexibility (particularly seasonal)

- Can support a range of price processes

- Can be used to back test against historic prices (“what margin would I have made…”)

- Relatively easy to include market dynamics (e.g. product granularity and b/o spreads) add additional complexity (e.g. integration into portfolio valuation framework)

|

- Not well suited to valuation & optimisation of fast cycle storage given limited spread liquidity & granularity in the prompt period

- Assumes “sub optimal” strategy of being fully hedged against expected profile (although this is a risk/reward trade-off)

- Relies heavily on the integrity of the simulation price process with care needed when choosing methodology (trade-offs involving complexity, calibration etc)

- Analytically complex and intensive

- Can be difficult to calculate meaningful Greeks

|

|

Constrained basket of spreads

|

- Accessible (can be implemented easily in Excel), transparent and explainable

- Clear link between the methodology and hedging strategy and underlying instruments

- Simple parameter estimation (can directly use implied volatilities but generally need to calculate cross maturity correlations using historic prices)

- Easy to calculate Greeks

|

- Doesn’t capture the true nature of the flexibility as the spread volumes are based on a deterministic optimisation of the inter-temporal optionality

- Undervalues within-month optionality as available spreads are generally constructed from tradable forward products (can significantly underestimate the value of fast cycle products).

|

|

Optimal

|

- Captures the “true” nature the problem:

- Spot optimisation of the path dependency optionality

- Uncertain (stochastic) prices – assumes lack of perfect foresight of future market prices but knowledge of day on day price behaviour.

- Can be used as a decision support tool for complex hedging strategies (i.e. delta hedging)

- Can be used to value all types of storage/swing contracts (e.g. equally valid approach for seasonal and fast cycle storage).

|

- Complex opaque methodology which can reduce transparency and faith placed in results

- Difficult to add extra dimensions (e.g. indexed contract prices or dual hub delivery optionality)

- Limitations of price models available for some methodologies (trinomial trees) but others support different methodologies through simulation (LSMC, SDP)

- Analytically intensive (especially for Greeks)

- Price model parameters generally not directly observable in the market.

|

Choosing a methodology

In our view, no single methodology is best. All approaches have strengths and pitfalls and an understanding of these is key to choosing the right tool for the job. There are however several key considerations to bear in mind:

- Hedging and optimisation strategy: It is important that ensuring that actual (rather than theoretical) hedging and optimisation strategies are reflected in the methodology, i.e.:

- Alignment of the methodology to the actual strategy to be employed in value monetisation – it is no use an Origination team pricing off an optimal approach if the Trading desk will implement a rolling intrinsic strategy.

- Ability of the model to support the strategy (e.g. it will be critical that realistic deltas can be produced if a delta hedging strategy is to be employed).

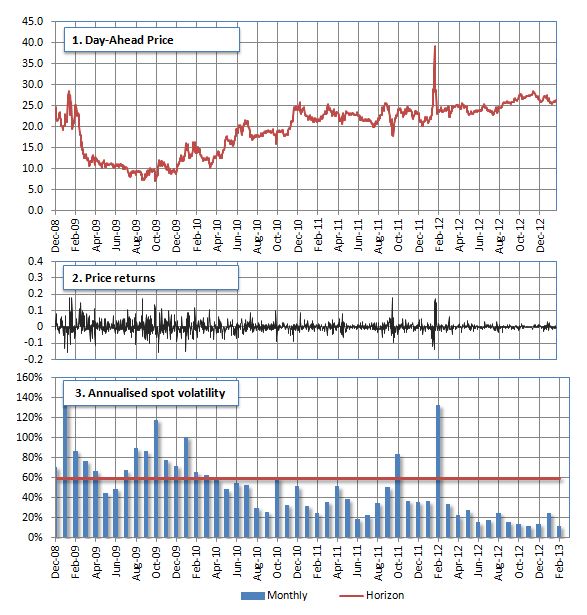

- Parameter estimation: Effectiveness and transparency of the methodology used are directly tied to the ease of input parameter estimation. The easier it is to observe or benchmark parameters against the market the better.

- Diversification: Two or three views on value are better than one. The use of several methodologies alongside each other is likely to build a depth of understanding as the value & optimisation of flexibility.

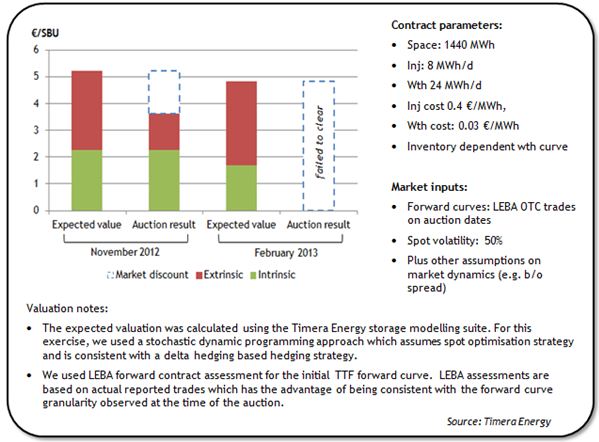

Finally it is important to recognise that the market will not pay for the expected value of an asset. A discount will be applied to reflect the costs and risks of monetising asset flexibility. Fortunately, the evolution of the market for gas flexibility products means that there are increasingly useful benchmarks (e.g. storage auctions, exchange traded options) to provide guidance on the market value of flexibility.