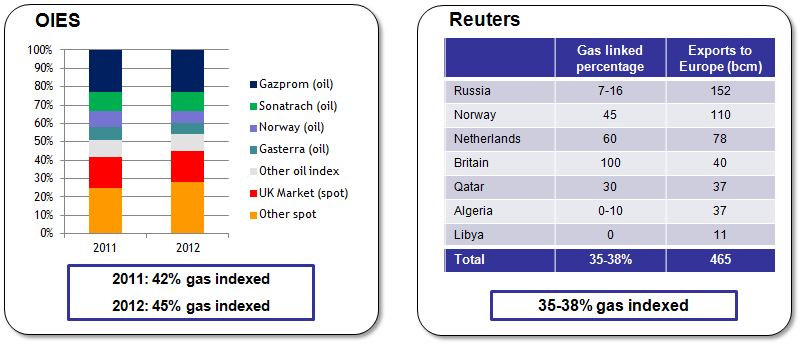

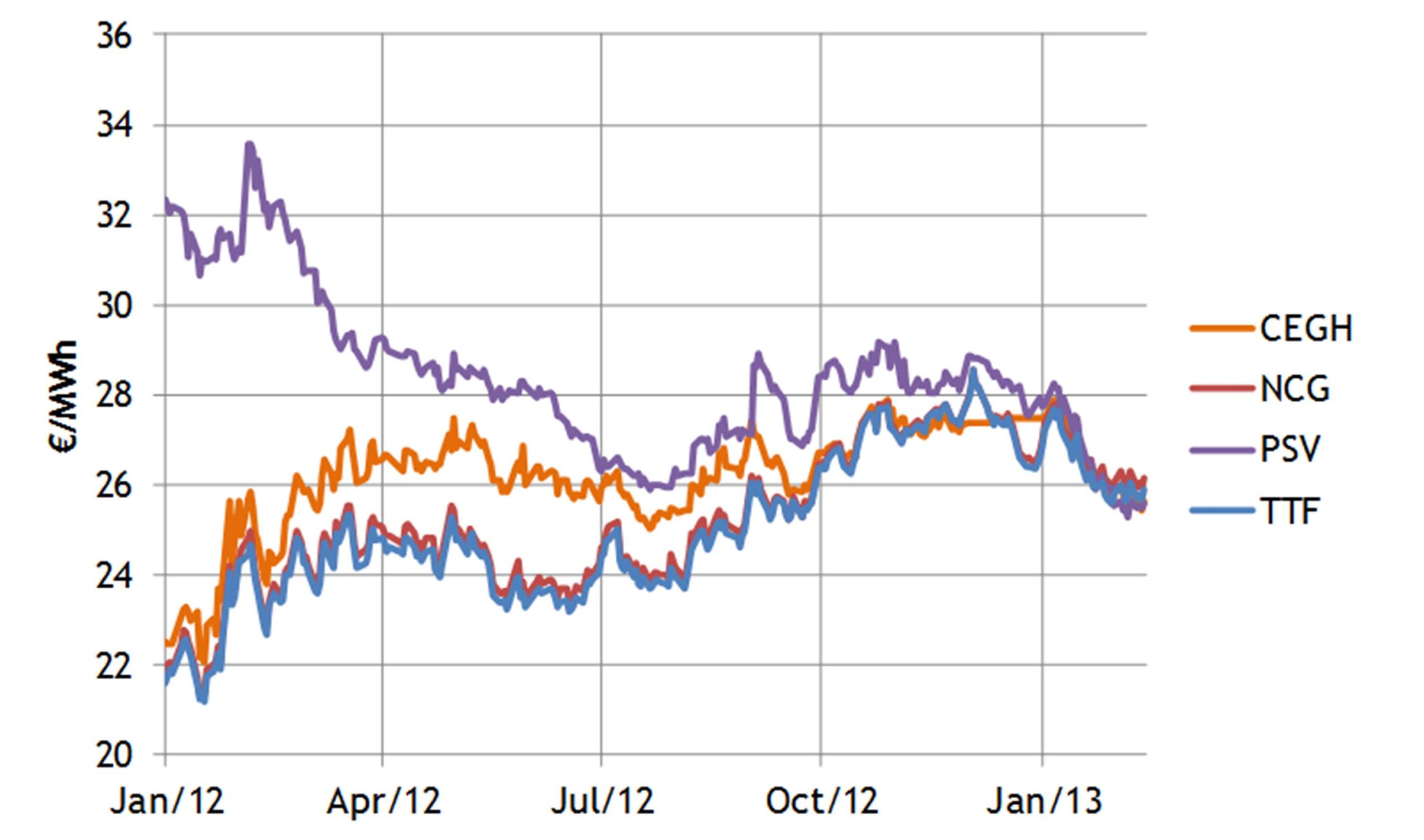

European and Asian gas markets are dominated by long term oil indexed pipeline and LNG supply contracts. The pricing of these supply contracts is a key driver of spot and forward market price dynamics. But because these contracts are highly commercially sensitive, publicly available contract price data is hard to come by. This is a particular problem for price benchmarks over a forward horizon. A common approach to filling this gap is to develop a proxy for the evolution of prices based on observable market price data for traded products.

Uses of proxy curves

There are many uses for proxy curves but these can broadly be grouped into two areas.

- Forecasting future price benchmarks for price series that are not directly observable:

- Understanding the future pricing of flexible supply contract volumes which are a key driver of marginal market pricing. For example, Russian supply contract prices are a key driver of the evolution of European spot and forward hub price dynamics. So a Russian supply contract price proxy can be used to analyse hub price behaviour.

- Forecasting and valuing indexed contract prices which have components that have no directly observable forward curves (i.e. developing a proxy for the index components). For example, some gas contracts formulas include oil product indices published government departments which have no forward prices available. A proxy for these indices can be used to forecast contract price, facilitating valuation of the contract.

- Analysing the implied exposures that influence a price series:

- Analysing the evolution of contract pricing influences. For example, it is possible to derive the evolution of the Asian LNG “S-Curve” slope or level against crude over time.

- Analysing and hedging implied exposures arising from contract indexation to non-standard prices. For example, the early Ruhrgas release gas auctions in the late 2000’s had the option to index to the Average German Import Price (AGIP) published by the German ministry. Developing a proxy for AGIP allowed the implied fuel oil and gas oil exposures to be calculated and hedged.

Methodology for developing proxy curves

The basic methodology involves developing a formula that allows the future values of a price series to be modeled as a function of price variables with transparent forward price data. A regression approach is typically used to identify the best fit linear equation against variables with different combinations of lagging and averaging rules. The basic linear equation is given below:

proxy pricet = a + b × component price1 (x1, y1, z1) + c × component price2 (x2, y2, z2) + …

where:

a is the intercept (equivalent to fixed price element of the formula)

b, c are slope coefficients that define the influence (or exposure) of each component

(x, y, z) are the averaging rules of each component (lag, averaging periods, duration)

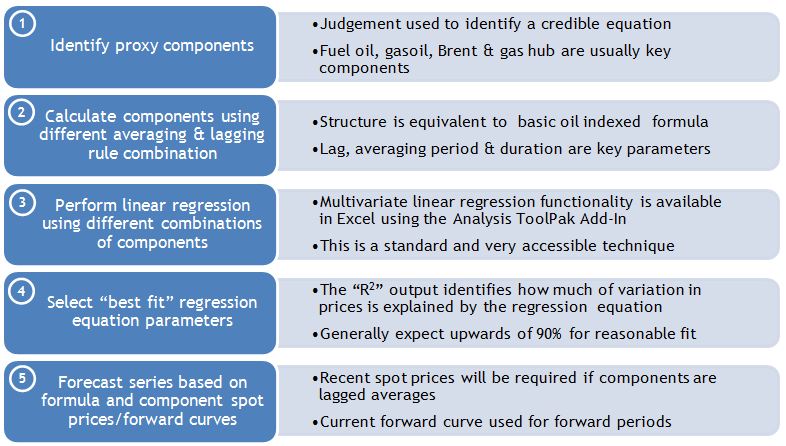

The regression allows the values for the constants (a, b and c) to be calculated but the different combinations of price component averaging are pre-calculated. Other more complex (e.g. non-linear) relationships are also used but are less common. The attraction of using a linear relationship is that it mirrors the structure of most contracts and linear regression is a relatively simple and accessible technique. The basic methodology is outlined in the diagram below.

Diagram 1: Proxy curve development methodology

The key outputs are the intercept and variable (component) coefficient or slope. The coefficient holds important information regarding how much exposure is implied by the proxy. The detailed lagging and averaging rules define the delivery periods of the exposure. At a high level the slope defines the implied influence that the components have over the prices that are being forecast. If the proxy is being used to forecast a contract price, these coefficients provide important information on the implied exposure which can be used to inform hedges.

|

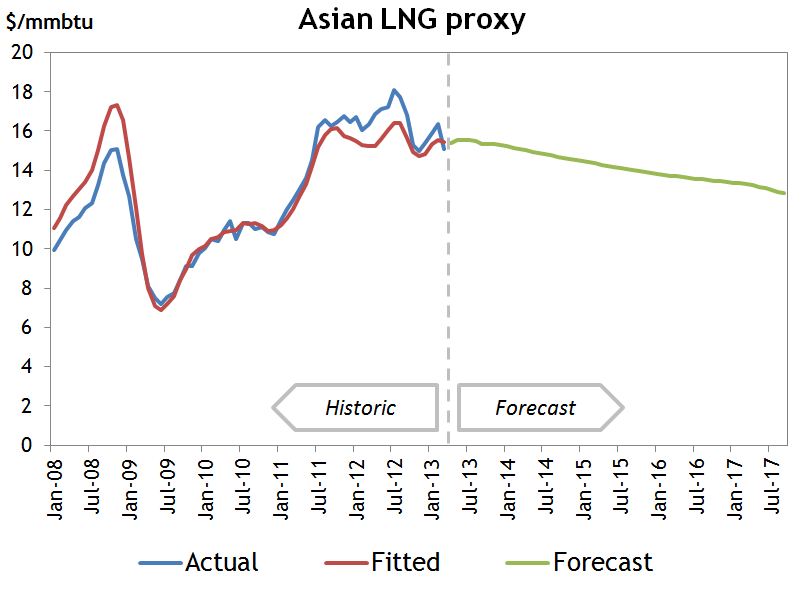

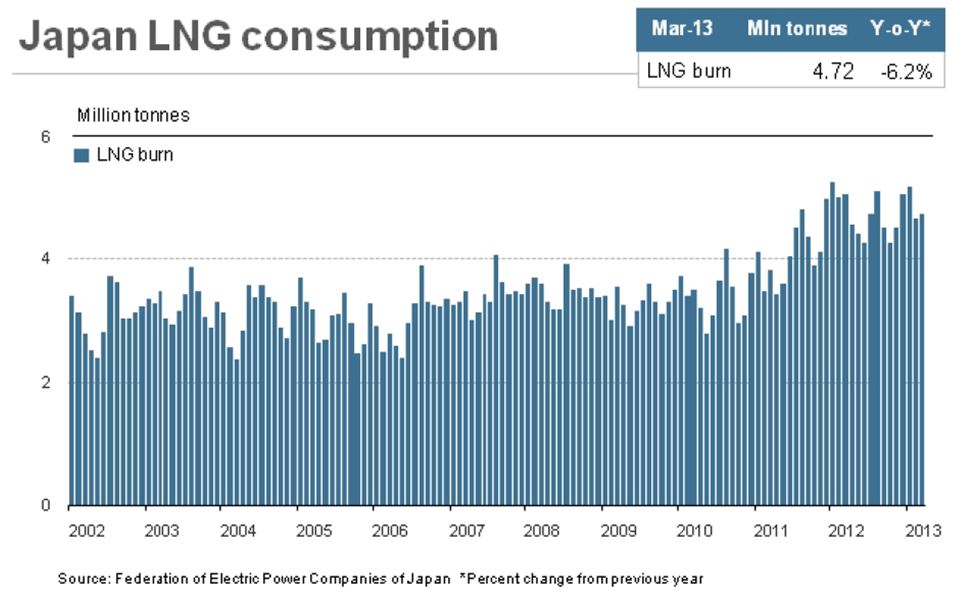

Case study: Developing an Asian LNG proxy Developing a view on forward Asian LNG prices is important for understanding global gas market dynamics, given the influence Asian pricing has on the LNG market. Despite some development in prompt indices there is no transparency in Asian forward pricing and as a result it is common for analysts to develop a proxy for Asian LNG prices. Crude oil is the predominant indexation term in Asian LNG contracts so it is a natural selection to use as the single proxy component. To demonstrate the concept we have developed a proxy for the World Bank Asian LNG price series against Brent crude. The table below shows the results of simple linear regression against a number of combinations of lagging and averaging rules.

For simplicity we have selected the proxy with the highest R2 (in red) but in practice there are other secondary issues which should also be considered. The chart below shows the actual price series against the fitted values and also the forecast of LNG prices based on the current Brent forward curve.

The World Bank Asian LNG benchmark is an assessment of average LNG prices that includes both contracted and spot purchases (the later only recently being included). As such it is influenced by the terms of long term contracts and short term fundamentals. Nevertheless the fitted proxy highlights many of the standard terms in long term contracts (e.g. the lag aligns to the lag of the JCC crude benchmark commonly used in contract indexation to Brent). It is interesting to note the influence of Brent curve backwardation on forward Asian LNG contract prices. The slope coefficient is significantly below crude parity (approx 17 %) but its value is highly sensitive to the historical periods included in the regression which highlights the evolution of the weighted average slope coefficients in long term supply contracts. |

Proxy curves provide a useful means for analysing the evolution of supply contract price dynamics. However proxy curves should also come with a health warning. The use of proxy prices to support commercial decision making (e.g. asset valuation and risk management), introduces proxy risk which warrants careful consideration. This is a topic we will focus on in a subsequent article that addresses some of the issues associated with the application of proxy curves.