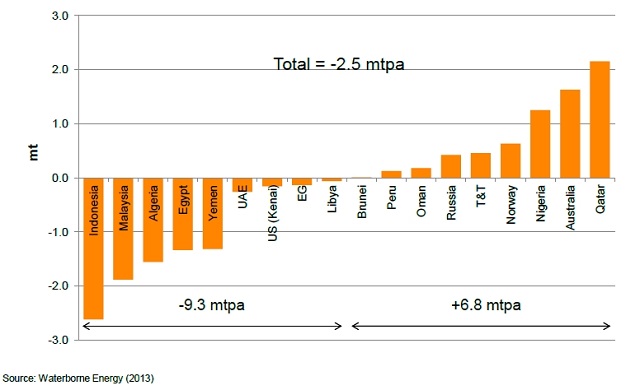

The practice of reloading an already discharged LNG cargo back onto a vessel for export appears to defy logic. But reloading of LNG has become an increasingly important factor driving European LNG flows over the last two years. Reloading activity is focused on specific locations where LNG supply is bound by contractual constraints. Despite the apparent inefficiency, significant profits have been made by reloading gas from Spain, Belgium and France for export to higher priced markets. But there are some important structural factors that are likely to impact the future of LNG reloading.

Why is reloading happening?

There are two key factors behind the reloading of cargoes in Europe:

- Fixed destination clause (Delivery Ex Ship) constraints in LNG supply contracts

- A structural premium of Asian LNG spot prices over European gas prices

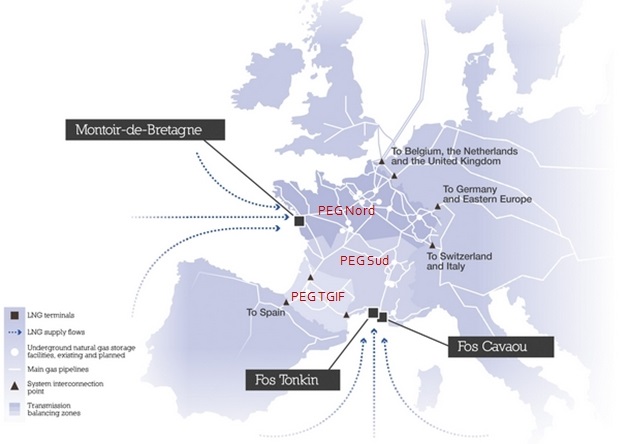

Fixed destination clauses only impact a subset of European LNG supply contracts. The majority of LNG supply into European terminals is contractually divertible, either as agreed in the original supply contract or as renegotiated by the buyer and seller. The exceptions are some inflexible supply contracts into Spain, France and Portugal, as well as Qatari LNG supply into Zeebrugge. This has led to the conversion of several regas terminals to enable the reloading of gas.

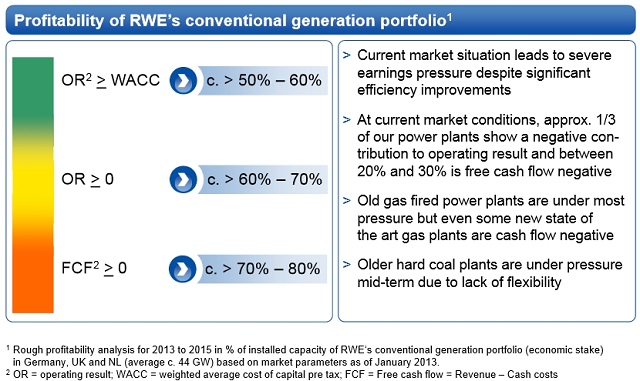

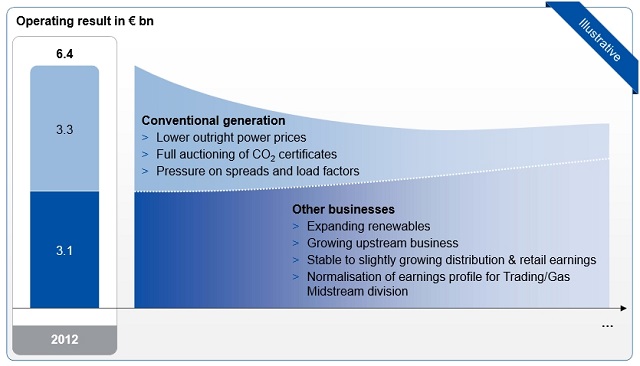

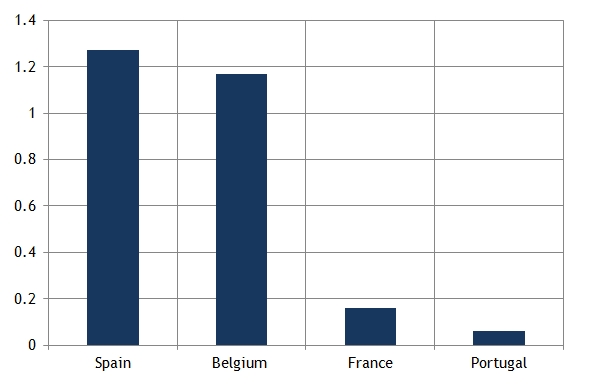

The source and scale of reload activity can be seen from the European volumes of re-exported gas in 2012, shown in Chart 1. These volumes are still relatively small as a proportion of total LNG supply into Europe, but are in addition to larger volumes of divertible LNG supply contracts.

Chart 1: 2012 European LNG re-export volumes mtpa (source GIIGNL)

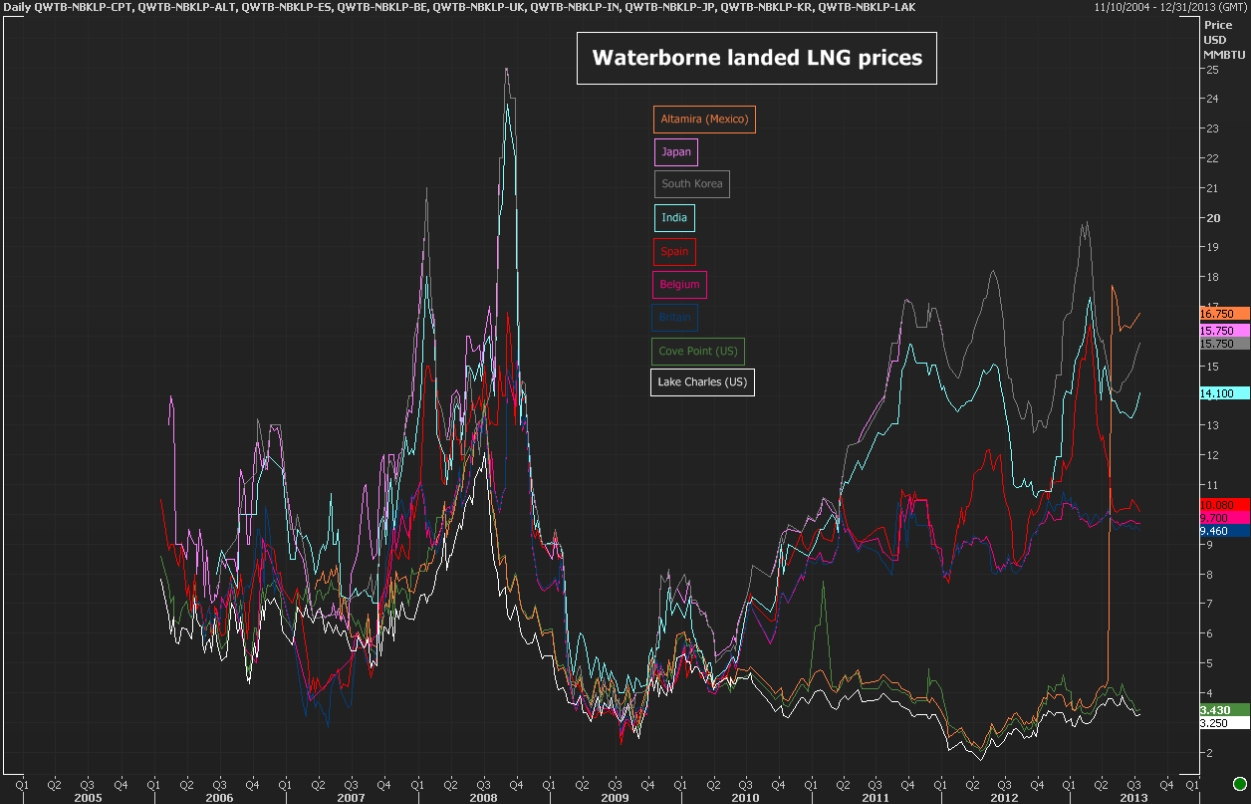

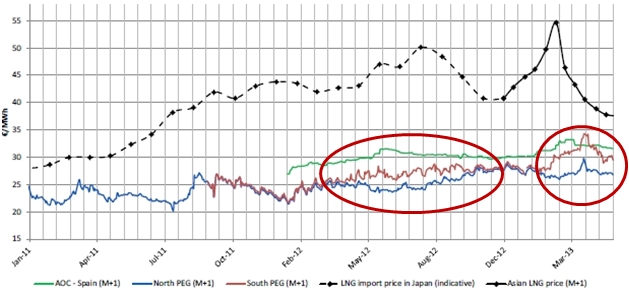

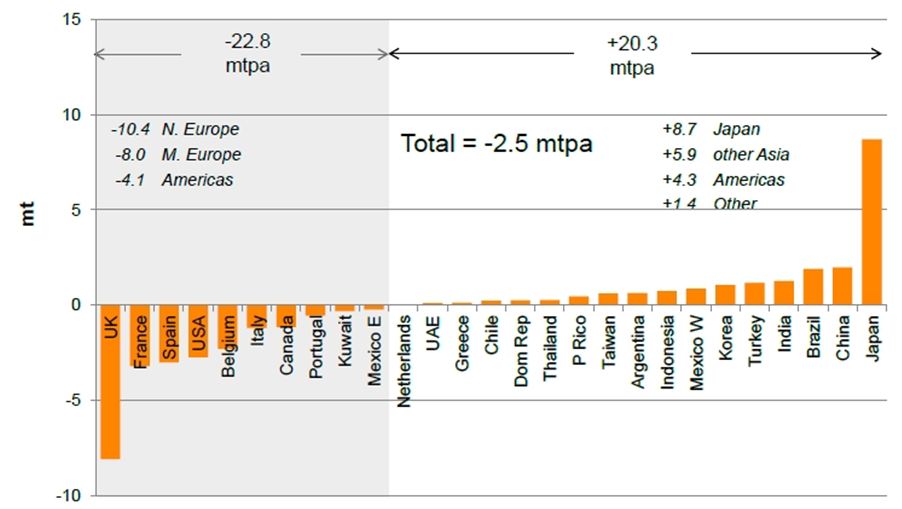

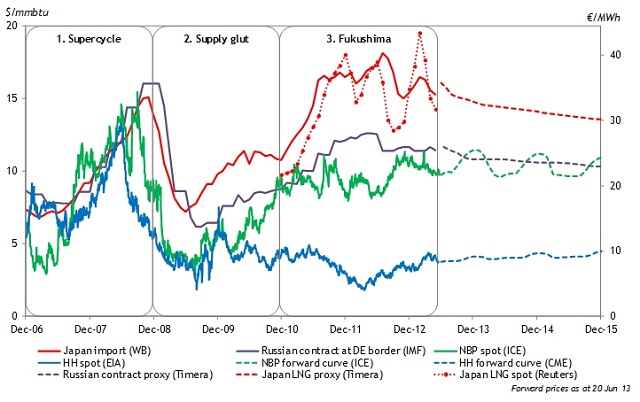

The structural Asian price premium that has seen a growth in European reloads is a specific phenomenon of post-Fukushima Asian LNG spot pricing. Reloaded volumes have broadly coincided with periods of high Asian or South American spot prices which have uncovered a substantial premium over shipping cost differentials. The incentive to reload can be seen by comparing the Japanese LNG spot price with NBP hub prices in Chart 2. In periods of high spot prices, the differential to send gas to Asia significantly exceeds the shipping cost of around $2.50/mmbtu.

Chart 2: Global gas price differentials driving reload volumes (source Timera Energy)

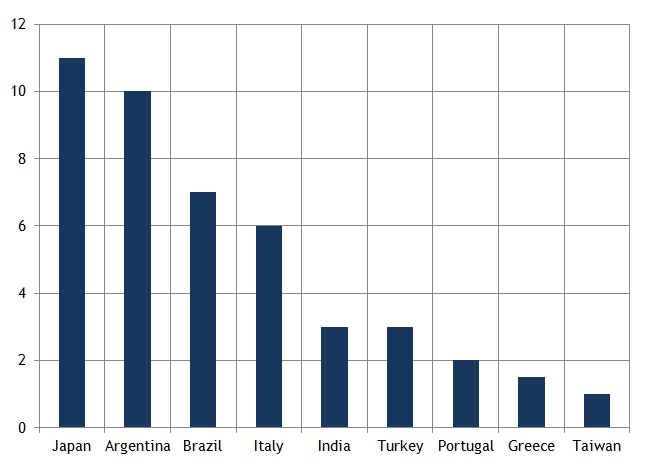

However European cargoes are not always re-exported outside Europe. Soft LNG spot prices in Asia and South America across summer 2012 caused the spread between these markets and Europe to narrow sharply. But the flow of reloaded cargoes shifted to premium European markets (mainly Italy and Turkey) with a lower absolute price premium but also lower shipping costs. Destination markets for European reloaded cargoes can be seen in Chart 3.

Chart 3: 2012 European LNG reloaded cargo numbers by destination (source GIIGNL)

What factors drive the decision to reload gas?

The flow of divertible LNG supply contracts tends to track shipping cost differentials reasonably closely. But the drivers of cargo reloads are more complex. A reloader of LNG incurs a set of direct costs levied by the terminal operators. These costs are typically regulated and vary by country but are in the order of $0.6-0.8/mmbtu.

But the party reloading gas also faces a number of logistical constraints and associated costs. Time is money with LNG, given energy lost via boil-off and transfer of gas. Reloading of gas blocks a terminal for longer than unloading (it can take 4-6 days), and terminals always provide priority access for regasification over reloading. There are also constraints around scheduling of reloads and how long gas can be kept in terminal tanks before it needs to be discharged. These logistical factors mean that the true cost of reload is well above the direct cost paid to the terminal operator. In other words a premium well in excess of shipping costs is required to incentivise the re-exporting of gas.

The future for European reloading

Although plans are being discussed to adapt other European terminals for reload (e.g. GATE), there are some factors working against growth in the re-exporting of gas.

From a global value perspective, reloading is an inefficient practice. Alleviating supply contract destination clause constraints to avoid reload costs should be a ‘win win’ outcome that increases value for a buyer & seller to negotiate. Over time, this will likely be reflected in supply contract renegotiation, reducing the requirement to reload gas.

However there are some practical considerations from an individual party perspective that may cause inefficiencies to remain. Reloading has the benefit to the LNG buyer of removing any requirement to share diversion upside with the seller (a practice that is common with divertible supply contracts). The seller (or LNG producer) may also place a premium on being able to control the flow of LNG. This is particularly relevant for Qatar, given the price it receives for uncontracted gas can be influenced by the impact of Qatari LNG flows on spot pricing.

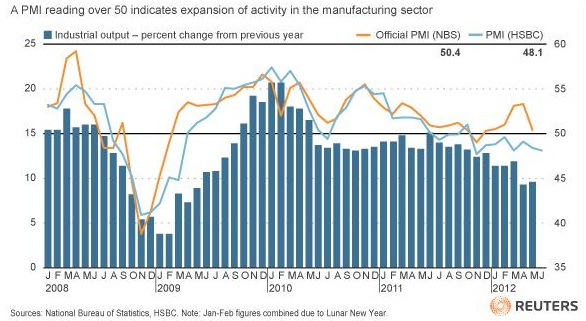

But perhaps the most important threat to reloading comes from a narrowing in global LNG Spot price differentials. A fall in Asian spot prices in Q2 2013 has already stemmed the volume of reloads this year. Looking forward, a slowdown in Chinese growth and Japanese nuclear restarts may continue to constrain global price differentials. In this environment, the reloading of European LNG is likely to be focused on shorter term opportunities driven by spot market volatility, rather than the structural flow of re-exported gas seen over the last two years.