2014 will mark the end of the energy only power market that has served the UK over the past two decades. By the end of this year the energy market will co-exist with a Capacity Market. The UK government has announced that it will stick to its aggressive implementation timetable. So barring any embarrassing delay, the first capacity auction will take place in November.

This auction will target the delivery of capacity in the winter of 2018/19. But the impact of the Capacity Market will be felt long before the end of the decade. The outcome of the 2014 auction will be a key driver of decisions to build, mothball or close gas & coal fired capacity over the interim period. This will have important implications for the system capacity margin and pricing in the wholesale energy market.

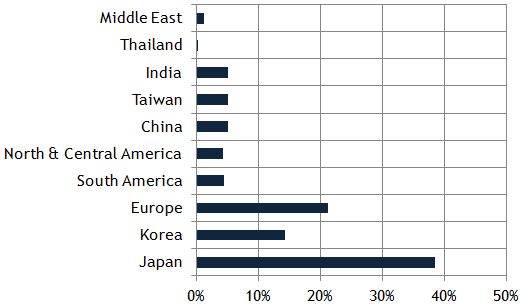

Implementation of the Capacity Market will fundamentally transform UK pricing dynamics and generation returns. It is also likely to be the blueprint for similar capacity markets across Europe. This is the first article in a series where we will address the structure, pricing dynamics and value/risk impact of the new Capacity Market.

UK Capacity Market 101

If you had recently returned to the UK power market after having been lucky enough to take a 5 year holiday, you would probably be in need of a stiff drink. Unfortunately whisky would do little to help you understand the government’s Electricity Market Reform (EMR) package. In fact anyone claiming to be able to enlighten you as to the workings and implications of EMR is likely to be dangerously removed from reality.

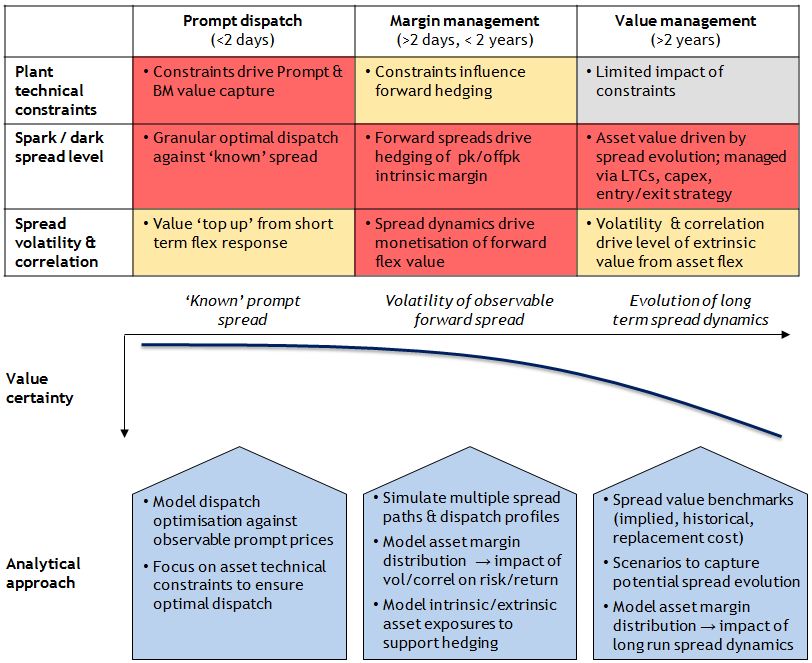

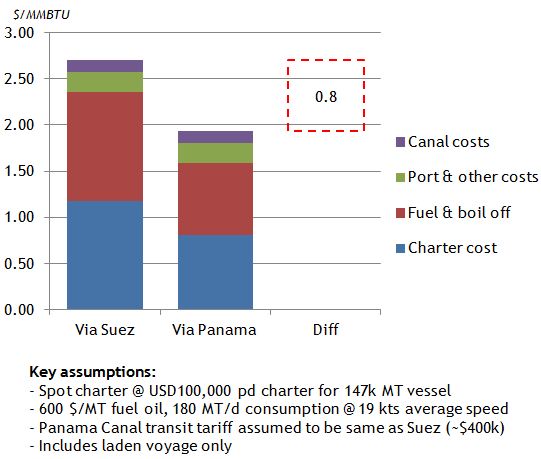

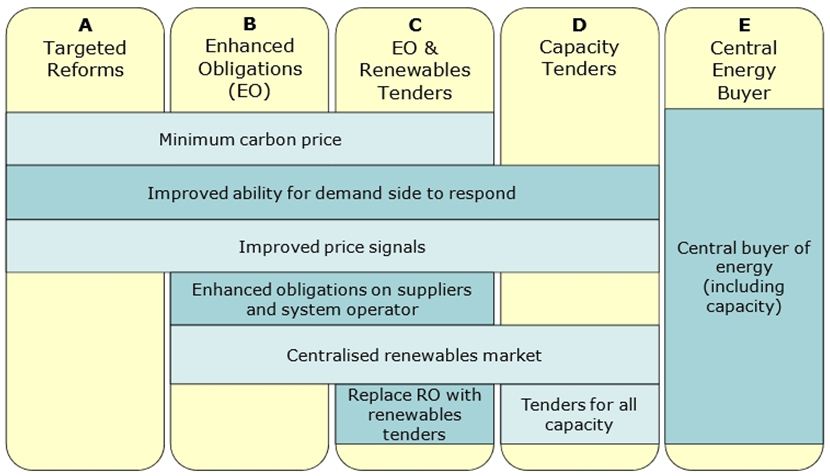

Even for those of us who have endured 5 years of Electricity Market Reform, the Capacity Market is a special challenge. It is essentially a correctional policy mechanism, attempting to compensate for the market distortions introduced by the other EMR policies. As a result the design is complex and it is still evolving. But we start by setting out a brief outline of the key elements announced to date, illustrated in diagram 1.

Diagram 1: Capacity Market elements & timeline into first delivery

Amount of capacity

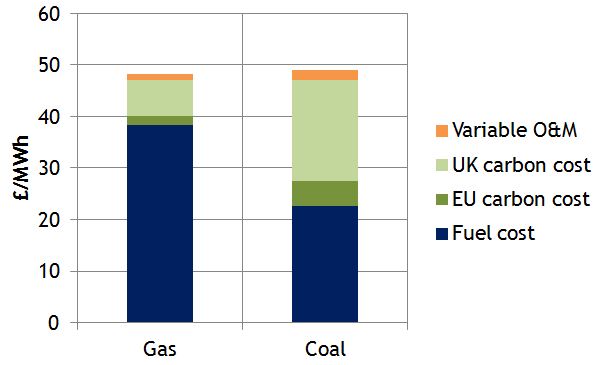

A reliability standard will be used to determine the target system capacity level. This standard will be based on what the government deems to be an acceptable loss of load expectation (or LOLE). The government has said it intends to set this at 3 hours per year (i.e. a system security level of 99.966%).

Guided by the reliability standard, National Grid as the System Operator will then undertake analysis to determine the volume (GW) of capacity required to meet this standard in each year. This volume will then set the target level for capacity auctions.

Participation

Capacity covered under other policy support mechanisms (e.g. FiT/CfD, RO, RHI) will not be eligible to participate in the Capacity Market. In practice this means the exclusion of most low carbon generation capacity, although Grid will of course still include this capacity in calculating the target system capacity level. Interconnection capacity will also initially be excluded, although with a view to later inclusion.

So Capacity Market participation will primarily be focused on new & existing gas plant, and existing coal plant. While in principle it is a voluntary market, generators will be strongly incentivised to participate. But existing assets have the option to retire rather than participate (e.g. at asset end of life). Demand side response and power storage assets will also be able to participate.

Auctions

The primary capacity auction will be held 4 years ahead of each delivery year. This is intended to allow the necessary lead time to develop new plant if successful in the auction. The government has said it also intends to hold a secondary auction at the year ahead stage with a view to ‘refining’ the capacity balance if required. The auction process will follow a descending clock format. Auctions will be ‘pay as clear’, i.e. all participants will receive the clearing price of the marginal bidder.

The government has said the Capacity Market will consist of 3 key forms of capacity agreement:

- 10 year contracts to support new generation assets

- Up to 3 year contracts to support major refurbishment of existing assets

- 1 year contracts for existing generators

Importantly, only capacity providers that incur costs above a certain threshold (primarily 1 and 2 above) will have ‘price maker’ status, i.e. be allowed to bid freely to set the capacity price. Bidding will however be constrained based on a government measure of the cost of new entry, with a view to protecting the consumer. Existing plant will participate as ‘price takers’ unless they can demonstrate costs incurred above a predetermined threshold (e.g. there may be a case for CCGT which are currently making a loss to recover costs that would otherwise have caused the plant to close by 2018).

We will consider capacity pricing drivers and benchmarks in more detail in our next article.

Trading

In principle the government intends to facilitate the secondary trading of capacity rights between auction and delivery. However this is likely to be restricted until the year-ahead of delivery. This element of the market design looks to be dosed with a healthy measure of academic fantasy. From the current CM design, it looks unlikely that capacity rights will be ‘commoditised’ to the point required to support significant volumes of secondary trading.

Delivery & payment

In the delivery year, Grid will manage periods of system stress via Capacity Market warnings. These will be issued 4 hours in advance of the requirement to deliver electricity. Holders of capacity agreements will be obliged to be available and ready to deliver a specified quantity of electricity when called upon in order to avoid financial penalties. The penalty structure is still under development but will likely be quite punitive, although with a mechanism to cap generator exposures. Grid will also have the ability to carry out spot checks on capacity delivery capability outside periods of system stress.

And the cost burden of this complex exercise? That of course sits with the end consumer and is likely to be smeared across suppliers based on contribution to peak demand.

Some key considerations for market participants

It is easy to get bogged down in the complexity of the market design. But with a basic understanding of the concepts it is possible to start to draw some conclusions on the commercial impact of the Capacity Market. We address a few of the more obvious considerations at a summary level below, before returning to explore these in more detail in our subsequent articles.

What will determine the capacity price?

The key factors driving capacity price in any delivery year will be (i) the projected requirement for incremental capacity and (ii) the cost of providing that incremental capacity. During periods where a capacity shortage is anticipated against the system target, participants will compete to provide incremental capacity. So the costs of CCGT refurbishment and of CCGT/OCGT new build will be key pricing benchmarks. During periods of adequate capacity margin, the capacity price is likely to be driven more by fixed cost recovery on existing assets.

While cost benchmarks will be important, the limited number of participants and complexity of market design will ensure that market power will also play a key role. We come back to capacity pricing as the key focus of our next article.

What are the implications for generation returns?

Historically, returns on conventional UK generation assets have been firmly focused on the wholesale energy market, with top-ups from participation in the balancing market and provision of balancing services. That is set to change significantly. Going forward this focus will expand to cover 3 buckets of generation margin: energy market, capacity market and balancing/ancillary services (which are likely to become an increasingly important source of gross margin).

Generation margin will shift between these buckets depending on factors such as system capacity, relative fuel pricing and plant type & location. While in principle capacity payments represent a more stable source of income than wholesale energy margin, the Capacity Market will carry an unwelcome exposure to regulatory risk and the potential for market manipulation. So a key challenge for generators will be to anticipate and manage the value & risk that accrues across these 3 margin buckets.

What are the implications for wholesale energy prices?

The commercial decisions of asset owners and investors will increasingly be driven by the return across all 3 buckets of generation margin. So there will be a key dependency between capacity pricing and wholesale energy pricing. A higher generation recovery from the Capacity Market will under normal circumstances adversely impact wholesale power prices (and vice versa).

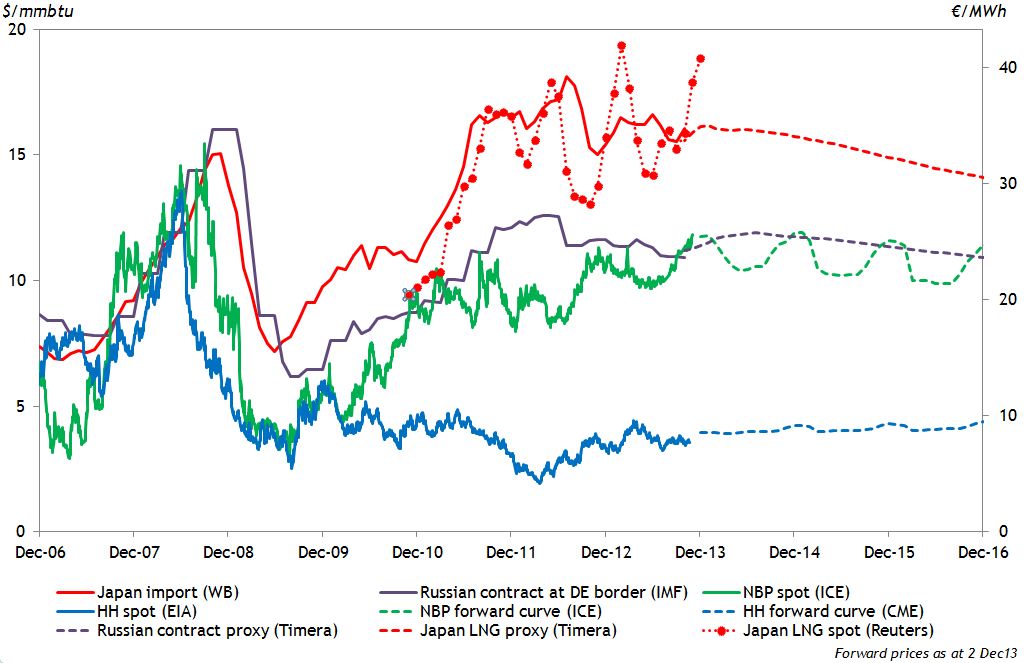

Variable generation cost (i.e. fuel, carbon, VOM) will remain the key driver of power prices. But the extent to which wholesale prices rise above variable cost will depend on capacity pricing and generator ability to exercise market power during periods of system tightness. The volume of capacity targeted by Grid via the capacity auctions will also be a key factor determining the extent to which power prices rise above variable cost.

What happens between now and 2018?

Despite trying to ram through the Capacity Market implementation by November this year, the government still faces several nervous years before it delivers any capacity. Any recovery in demand or further closure of existing CCGTs may bring on major system stress prior to 2018. As a result, the government is in the process of implementing Supplemental Balancing Service payments which give Grid the freedom to contract capacity in advance of 2018.

This means the ancillary/balancing services generation margin bucket may play an increasingly important role. Existing gas and coal plant (particularly older assets close to retirement) may have significant leverage in negotiating reserve contracts with Grid as the system capacity margin tightens.

The way forward to the first auction

It would appear to be ten minutes to midnight on an implementation timeline for such a complex policy mechanism. But there are still a number of key areas of contention that are emerging from the industry consultation process. As a result there has to be a meaningful risk of delayed implementation or a disorderly first auction.

Perhaps the greatest focus is on the structure of capacity contracts and the constraints around capacity pricing. For example, generators are lobbying strongly for longer contracts to support both new build and life extensions. The supporting arguments revolve around increasing bankability and reducing the cost of capital. There is also contention around use of an OCGT asset as the basis for new entry cost to set bidding thresholds. While there is a theoretical link between OCGTs and capacity cost, it is the cost structure of CCGT assets that dominates the UK capacity options.

Many of these unresolved issues are quite fundamental to the structure of the market. But it is still possible to draw some sensible conclusions on Capacity Market implications. For example on the pricing of capacity, impact on generation returns and implications for asset investment. As the clock ticks down to the first auction, we will explore these issues in more detail over several subsequent articles.

We offer bespoke workshops on the commercial implications of the Capacity Market. These can be tailored to address issues such as business impact, asset strategy and market pricing dynamics. If you are interested please

contact us.