Flexibility value has become a popular concept in energy markets. At a qualitative level the benefits of flexibility are reasonably well understood. Increasing intermittency in power markets requires flexible backup. This has a knock-on impact with gas markets where supply flexibility is evolving in response hub price signals.

What is less well understood is how to analyse and quantify the flexibility value of gas and power assets. Investors in particular continue to be wary of paying for ‘extrinsic value’, the more technical jargon for flexibility value. This is with some justification given that extrinsic value is often inflated via theoretical modelling analysis, rather than being demonstrated via a more practical analysis of how asset flexibility can be realised in the market.

But current market conditions are forcing asset investors and owners to confront extrinsic value. Relative pricing dynamics mean that flexible gas & power assets increasingly have ‘at the money’ optionality characteristics, meaning extrinsic value is a key component of asset value. Take two examples:

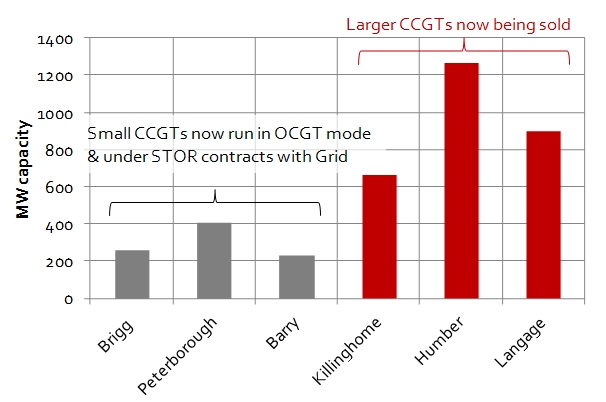

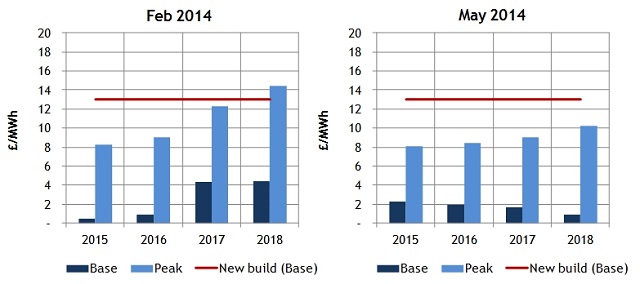

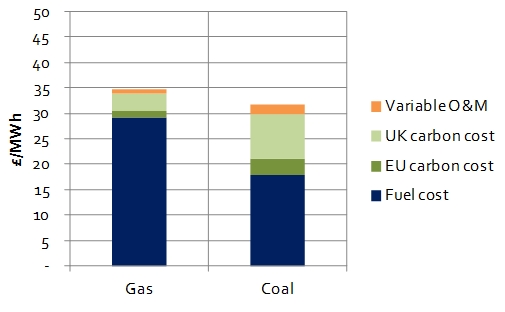

- CCGT’s across Europe have been driven out of merit as coal prices have fallen relative to gas prices. As a result most assets have variable costs that are at or above the level of wholesale power prices. In other words they can be characterised as strips of ‘at the money’ or ‘out of the money’ options with capture of extrinsic value being a key focus.

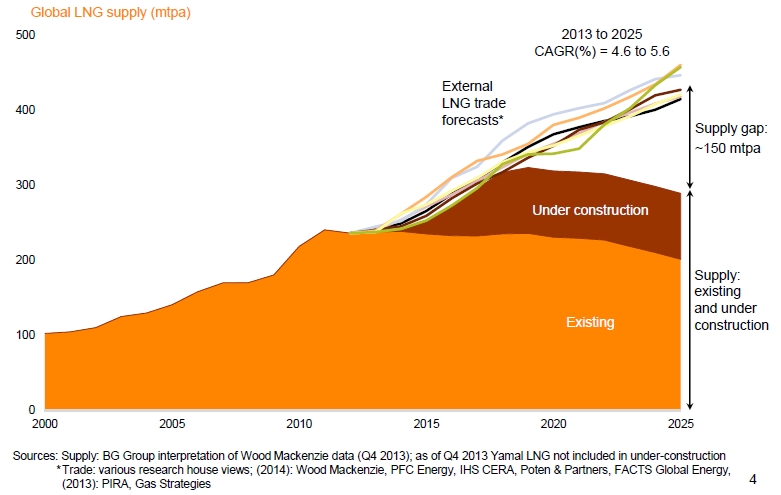

- Gas storage assets have faced a steady decline in seasonal (summer/winter) hub price spreads over the last 5 years. As a result the intrinsic value that can be locked in against forward prices has fallen and storage flexibility has become more focused on monetising volatility across spot and forward prices (extrinsic value).

Extrinsic value is about more than prompt volatility

There is a common misconception that extrinsic value is all about capturing short term (or prompt) volatility in market prices. While a theoretical modelling approach may promise high returns from flexibility to respond to short term price movements, there are practical limitations in monetising this value. Risk appetite, liquidity constraints and transactions costs all present hurdles. And given day-ahead and within-day prices for gas and power can be very volatile, forward hedging of assets tends to reduce short term extrinsic value access.

However extrinsic value is more than just prompt volatility. To appreciate this concept it is important to clarify the two components of asset value:

- Intrinsic value refers to value that can be observed (and hedged) against current forward market prices.

- Extrinsic value refers to all other value that can be generated by the flexibility of the asset to respond to changes in forward prices, but cannot be observed/hedged at the time of valuation.

As well as short term price fluctuations, extrinsic value includes more substantial deviations in commodity prices that were not observable in forward prices at the time of asset valuation. The impact of the current slump in summer gas prices on gas storage asset value provides a useful case study.

Gas storage value from hub price curve swings

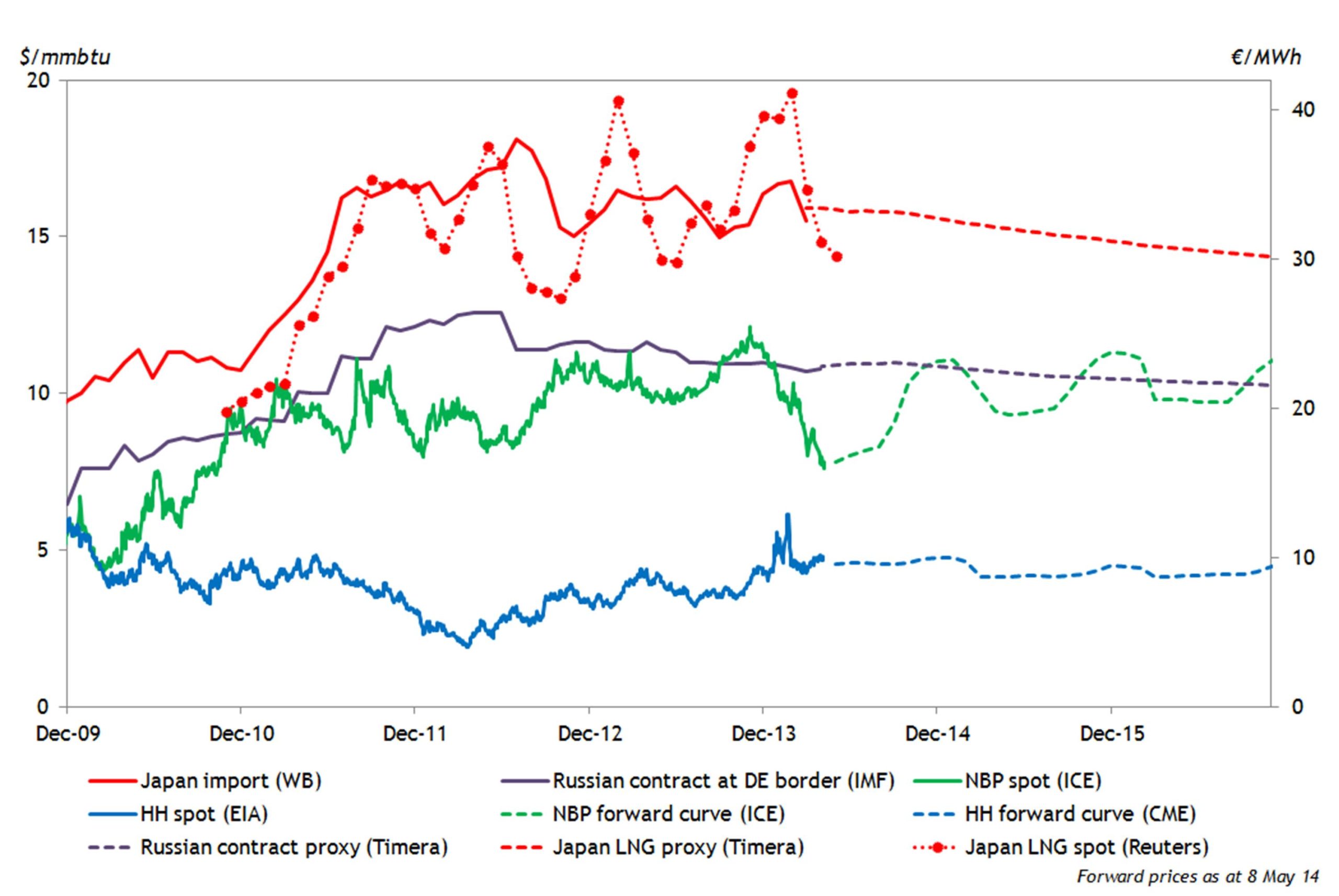

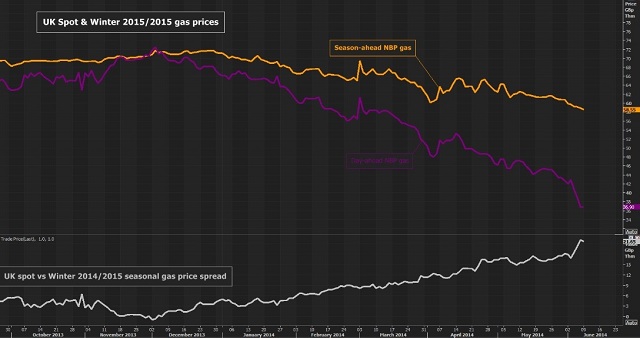

At the start of 2014 the UK NBP price spread between Summer 2014 and Winter 2014/15 was about 6p/th. With the slump in summer gas prices that has ensued across the first half of this year, the spread between prices this summer and Winter 2014/15 has blown out towards 20p/th as illustrated in Chart 1 (yellow line shows winter contract, purple line NBP day-ahead spot and the white line the spread between these two prices).

Chart 1: UK NBP price spread between spot and Winter 2014/15

Analysis of gas storage asset value based on the extrapolation of intrinsic forward price spread conditions, misses the extrinsic value generated from price movements like the one shown above. This is not extrinsic value generated by short term spot price volatility (although spot vol has also increased over this period). But it is value generated from within year shifts in the relative pricing of gas along the forward curve. The impact of the current supply glut across European hubs is focused in the current year with limited impact from 2015 and beyond (e.g. the Summer 15 vs Winter 15/16 NBP price spread is only around 8 p/th).

Values for CCGT and gas storage assets have plummeted as intrinsic values have fallen over the last 5 years. Some of these assets are not viable investments given structural weakness in margins relative to fixed costs. However there are also increasingly opportunities to buy good assets cheaply (e.g. at a fraction of replacement cost).

In order to do justice to flexible asset valuation under current market conditions, the valuation approach needs to reflect:

- A realistic simulated distribution of asset returns capturing potential movements in commodity prices

- A pragmatic view as to how price movements can be monetised via asset flexibility response

Over time, assets are increasingly likely to go to buyers who understand how to quantify, risk adjust and monetise extrinsic value.