This blog is focused on gas and power markets. But every few months we take a step back and look at the impact of the broader commodity market environment. With front month Brent crude oil plunging more than 20% over the last few weeks and a broader sell off across commodity markets, it seems like an opportune time to revisit this theme.

There are two main factors behind the recent commodity price falls. Firstly, there are increasing concerns about weakening global economic growth and hence commodity demand. The IMF last week fired a warning shot on global growth, raising particular concern about Europe slipping into another recession. Despite massive monetary stimulus, the Japanese economy is also treading water. And importantly for commodity demand, the Chinese economy still appears to be going through a period of consolidation at lower levels of growth.

The second factor is a surge in the US dollar across the last three months. This reflects a shift in the balance of monetary expansion away from the US and towards Europe and Asia. Over the next year or two it looks like both the Eurozone and Japan will rely on more aggressive monetary easing to respond to the dual threats of deflation and weakening economic growth. The US currently has the healthiest growth & employment scorecard and may start to raise interest rates again next year. This shift in relative monetary policy stances is driving the movement of capital from other currencies into the US dollar. This is important for global commodities (which are traded in USD terms) because there has historically been a significant negative correlation between commodity prices and the dollar.

With these two factors as context we now take a look at the recent evolution of oil and coal prices.

Oil takes a dive

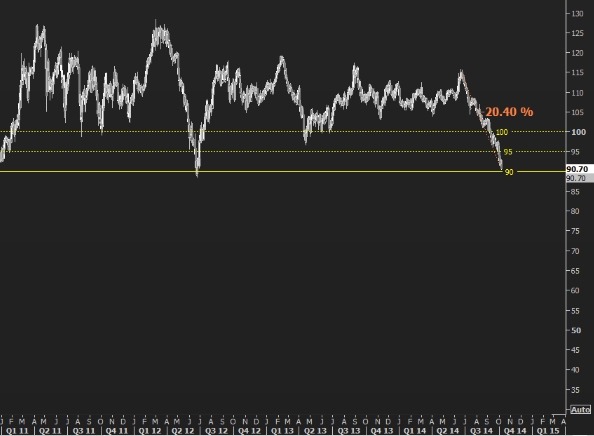

The front of the Brent crude oil curve has been trading in a range between 90 and 125 $/bbl since the start of 2011. The last few weeks have seen a sharp 20% decline in the front month contract to break support at the bottom of this range, a move which has got a lot of press. As well as the two factors described above there are a couple of other factors of specific relevance to the decline in oil prices:

- US unconventional oil production keeps expanding to new record levels, which is contributing to the weight of global supply in a weaker demand environment.

- OPEC does not appear to be presenting a convincing near term response to counter the recent price fall. In fact Saudi Arabia appears to be comfortable with the current price fall according to Reuters.

As much as the recent move in the front of the oil curve has generated excitement, there has not been much follow through when you look several years forward. The recent move down in near term contracts has resulted in a very flat curve. But this is still anchored above 90 $/bbl in 2020. The current oil price decline will become a much bigger story if the fall below 90 $/bbl in the front of the curve, starts to materially pull down longer term prices in the tail.

Chart 1: Evolution of Brent crude front month contract since 2011 ($/bbl)

Source: Reuters

Coal continues to slide

The coal market has been a story of steady price decline for the last three years, as shown in Chart 2. It is well known that China sits at the centre of the global coal market as the world’s biggest consumer. What is less well known is that China is also the world’s biggest producer of coal. Although a number of Chinese mines look to be uneconomic at current price levels, China’s production has continued to expand, reducing import demand. China has also recently slapped tariffs on imported coal in a worried attempt to protect struggling domestic miners. The situation in China is weighing on an already oversupplied seaborne coal market. This is not helped by weakening US gas prices which continue to favour gas-fired generation over coal.

Chart 2: Evolution of coal API#2 ($/tonne)

Source: Reuters

Global coal price weakness is however starting to induce curtailment of supply in large exporting countries. Australia in particular has had several mine closures and cutbacks as a result of weak export prices and a relatively high production cost base. More closures of export mines are going to be required to stabilise coal prices. But prices have been at or below the long run marginal cost of new production for some time now. So the coal market has progressed to a more advanced stage of reacting to price weakness. The oil and gas markets on the other hand are only just starting to confront the prospect of a period of oversupply.