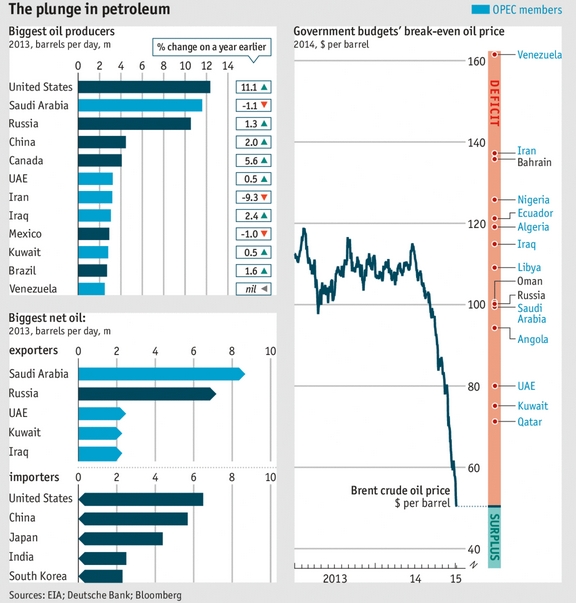

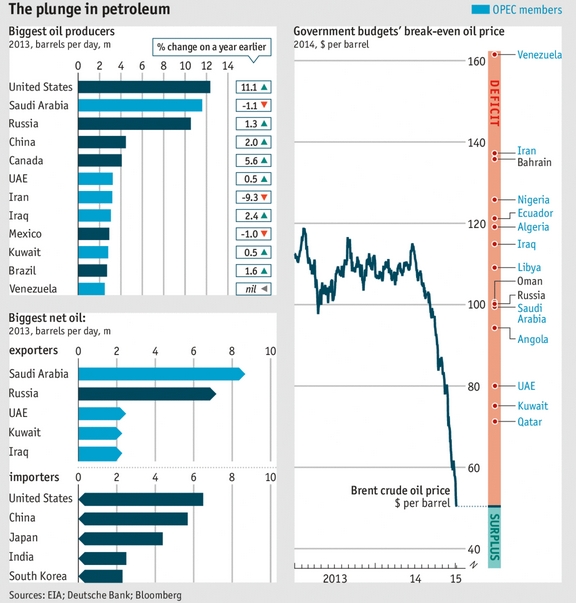

There have been some big moves in commodity prices and currencies so far in 2015. Sharp declines in oil, gas and coal prices have reduced the fuel costs of European thermal generators. But have these fed through into improved margins for gas and coal plant owners? The answer to this question is somewhat market and asset dependent. In this article we explore how commodity price movements are influencing generation margins in Germany and the UK.

Market moves in Q1 2015

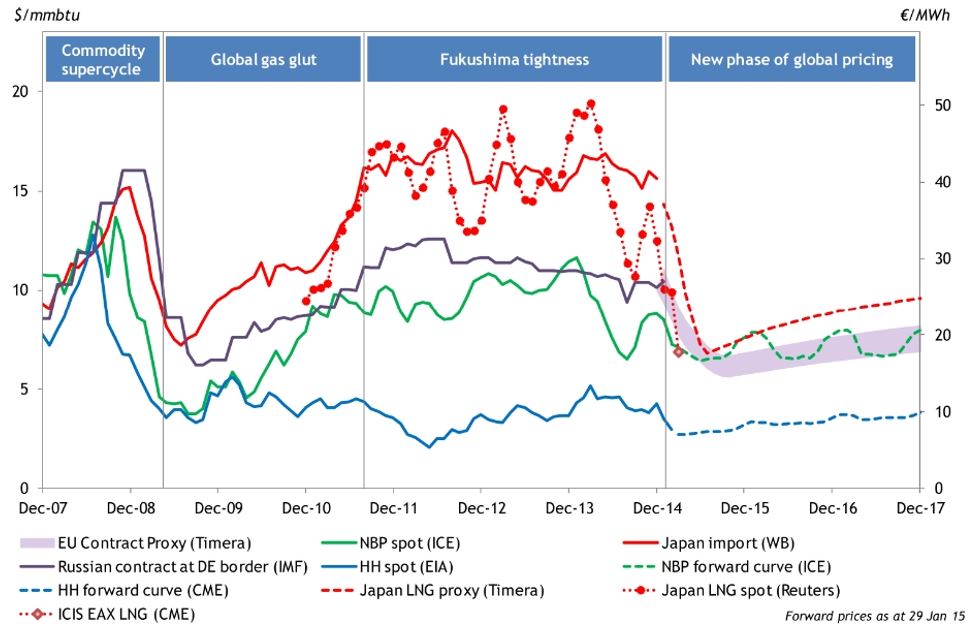

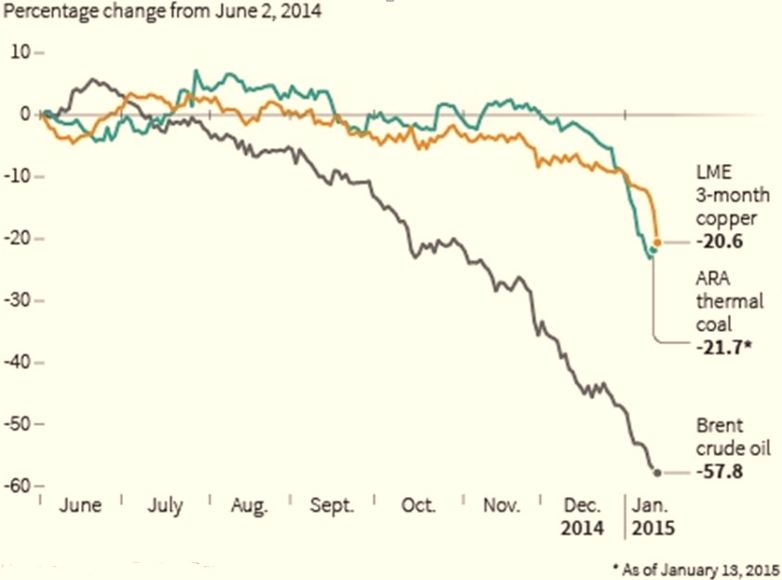

The sharp correlated decline in oil, gas and coal forward curves that started in Q4 2014 continued through January. There was some respite in February as crude prices bounced in anticipation of US production curtailment. This triggered a recovery in European gas hub curves, reinforced by the threat of Groningen production cuts. Even long suffering ARA coal prices managed a brief February rally, as Glencore’s announcement of global production cuts hinted at a supply side response to price weakness.

But oil, gas and coal prices are falling once again across March. The February bounce looks to have been a temporary phenomenon rather than the start of any structural recovery. The Brent curve is sliding again, with the front month contract falling back towards its January lows around 50 $/bbl. NBP and TTF curves are falling in sympathy, with prompt prices weakening into a mild spring. And ARA coal prices remain below 60 $/t and close to a nine year low as shown in Chart 1.

Chart 1: API2 2015 coal futures price chart

Source: Reuters

Generator fuel prices have also been buffeted by big moves in currency markets. While coal prices have fallen sharply in USD terms, this has been significantly offset by USD appreciation against the EUR. The USD has risen approximately 20% against the EUR since last September (about 10% against GBP).

The speed and scale of USD appreciation over the last six months is unprecedented over the last 30 years. It suggests a structural shift towards a stronger dollar as major European and Asian countries scale up monetary expansion in an attempt to fight economic weakness and deflation. Implied FX volatility has also increased sharply over this period, a red flag that it is prudent to place an increased focus on FX risk within energy portfolios.

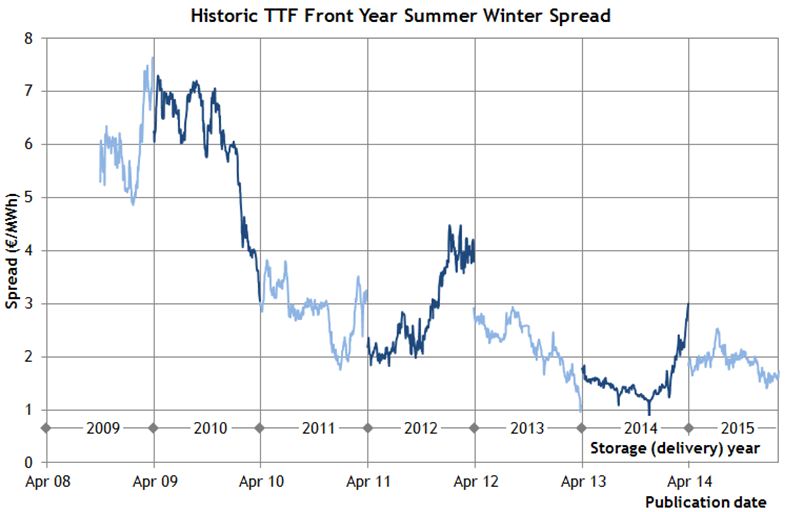

Forward spread dynamics into 2015

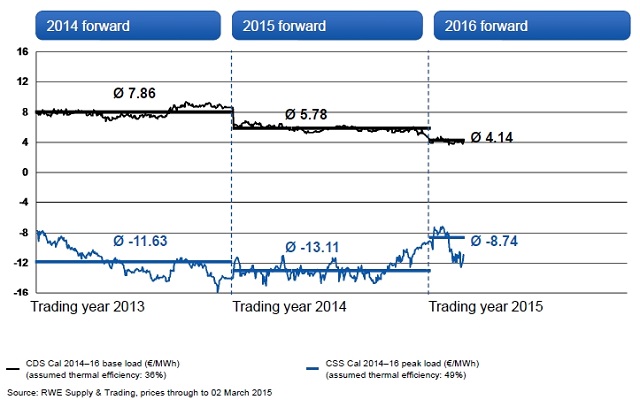

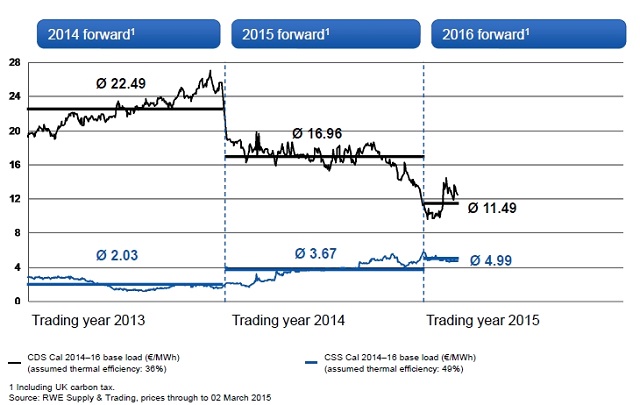

While absolute commodity prices are of interest to generators, the primary driver of plant margins is relative moves across power, fuel and carbon prices. Charts 1 and 2 illustrate some interesting dynamics in the evolution of forward market implied gas and coal plant generation margins so far this year.

Chart 1: Germany clean dark and spark spreads

Source: RWE

German coal plant margins: As we have set out previously, coal plants dominate the setting of marginal prices in the German market. This explains the relative stability of German forward Clean Dark Spreads (CDS) in Chart 1. The gradual decline in forward spreads over the last three years reflects the increasing penetration of renewables as well as the commissioning of new and more efficient thermal capacity.

German CCGT margins: With coal plant setting marginal prices, the big decline in forward gas hub prices in Q4 2014 (as oil fell) has fed through into a significant bounce in Clean Spark Spreads (CSS), albeit still in deeply negative territory. Chart 1 shows the CSS recovery reversing somewhat across February. But the chart (using forward price data from Mar 2nd) does not show the subsequent increase in CSS over the last two weeks as gas prices have once again fallen.

Chart 2: UK clean dark and spark spreads

Source: RWE

UK coal plant margins: The UK shows quite different margin dynamics given gas-fired plant dominate marginal price setting. Unlike in Germany, oil/gas price declines feed through directly into lower forward CDS as can be seen in Chart 2. This dynamic hints at tough times ahead for UK coal generators as they are faced by headwinds from both falling gas prices and an increasing carbon price floor (which will jump to 18 £/t in April).

UK CCGT margins: With CCGTs on the margin in the UK, CSS are relatively stable. The gradual recovery in gas-fired generation margins across the last 12 months reflects the tightening UK capacity balance. Although two mild winters (13/14 & 14/15) have helped to cap forward CSS recovery to date.

Overall the margin environment for gas and coal fired generators is still fairly bleak. However this is continuing to translate into capacity closures, good news for the margins of remaining generators. For example in the UK, Centrica and E.ON have recently announced their intentions to close CCGT plants after missing out in the first capacity auction. Weakness in forward CDS is also making life increasingly difficult for UK coal generators without capacity contracts. But commodity price movements may also have an impact on the relative value of gas versus coal plant.

Watch for gas vs. coal switching going forward

The last four years of commodity price evolution have firmly favoured coal plant margins over gas plants. Current market pricing still favours coal plants. But gas vs coal plant switching may yet become an important story in 2015.

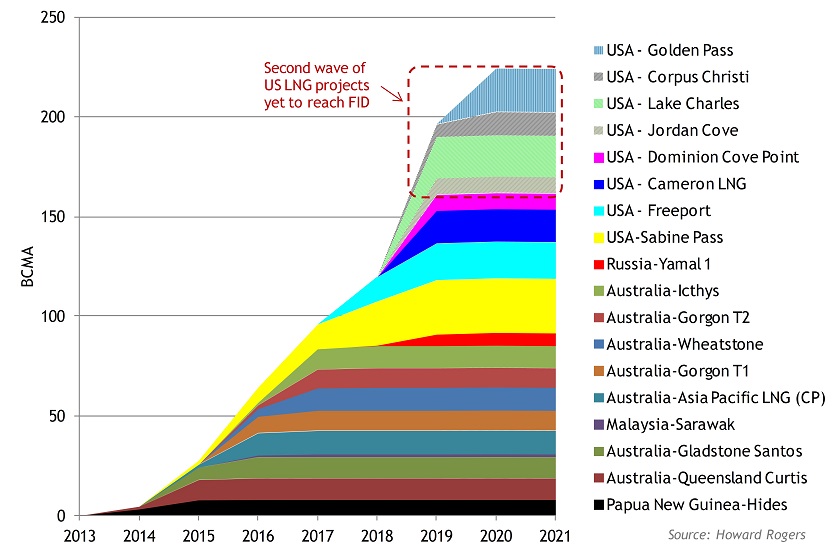

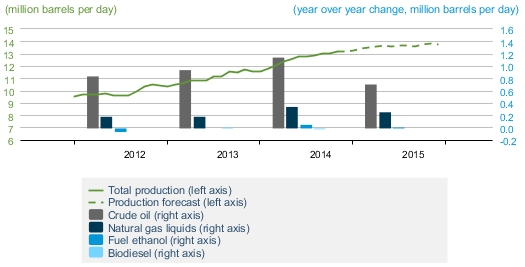

Global coal prices are now at levels where significant volumes of production are being curtailed. US coal producers look particularly vulnerable as the USD strengthens. This may act to stem further price declines even if global demand remains weak. Oversupply in the global gas market on the other hand is a relatively recent phenomenon. And rather than being curtailed, supply is ramping up substantially over the next 3 years (as we set out here).

The risk of further falls in European gas hub prices has been one of our key themes this year. These may act to close the gap between gas and coal plant competitiveness to the point that switching takes place again. The UK power market is the ‘canary in the coal mine’ for switching, given the penal impact of the carbon price floor on coal plant competitiveness. We will come back to analyse gas vs. coal switching dynamics in more detail soon.