The oil market is currently focused on the Saudi dominated OPEC’s strategic reaction to lower prices. There is no ‘gas OPEC’ per se; but there are important strategic questions around how Russia responds to lower gas prices.

The importance of Russia is not just the scale of its production and reserves, but that it is a key supplier of gas to both Europe and (in the future) Asia. Russia also has an important production cost advantage over new LNG liquefaction projects. But what are the drivers of Russian strategic thinking and how may these playout to influence global gas prices?

Russia: the world’s key gas producer

Russian domestic market gas consumption has stagnated, declining from 424 bcm in 2011 to 409 bcm in 2014. At the same time non-Gazprom Russian gas producers have progressively competed for the Russian market; in 2014 their domestic market share reached 30%.

Gazprom’s long term contract exports to Europe have been confined in a 140 to 160 bcma range since 2009. Its exports to FSU countries have fallen from around 80 bcm in 2011 to some 43 bcm in 2014. This has meant Gazprom’s upstream Russian production has been on a downward trend since the beginning of this decade.

It is important to distinguish ‘production’ from ‘production capacity’. In anticipation of higher European demand growth and continued dominance of the domestic market, Gazprom invested in the Bovanyenko Yamal gas field and currently has some 100 bcma of excess productive capacity.

In Asia, Russia’s only current export channel is the Sakhalin 2 LNG project (14.5 bcm in 2014) selling to Japan and South Korea with minor volumes to China, Taiwan and Thaliand. Gazprom has a 50% ‘plus one share’ stake in this project.

Two pipeline projects are in development to supply Russian gas to China. The first is a reduced version of an integrated scheme ‘the Power of Siberia’. This would develop currently discovered, but stranded, East Siberian fields to supply 38 bcma of gas to north east China. It was also intended to provide feedgas to a new LNG terminal at Vladivostok, although the LNG element has now been put on hold. The second, termed the ‘Altai pipeline’, connects 30 bcma of the current West Siberian ‘gas bubble’ of excess productive capacity to north west China. The timing of this potential 68 bcma of pipeline supply to China is uncertain, as indeed is whether both projects will ultimately proceed.

One factor driving this uncertainty is the future gas demand trajectory of China in the ‘new normal’. The second is the impact of sanctions on Russia on access to external financing. Although LNG technology is not specifically targeted by current US sanctions, the apprehension that it might in future become so, and the challenge of raising finance for such projects has in effect limited new LNG projects to the Novatek-led Yamal project.

Russia’s ‘Pivot to Asia’ has thus hit the buffers of reality in today’s lower Asian demand and gas price world with the additional restrictions imposed by current and potential future sanctions.

Russia’s role in the global gas market

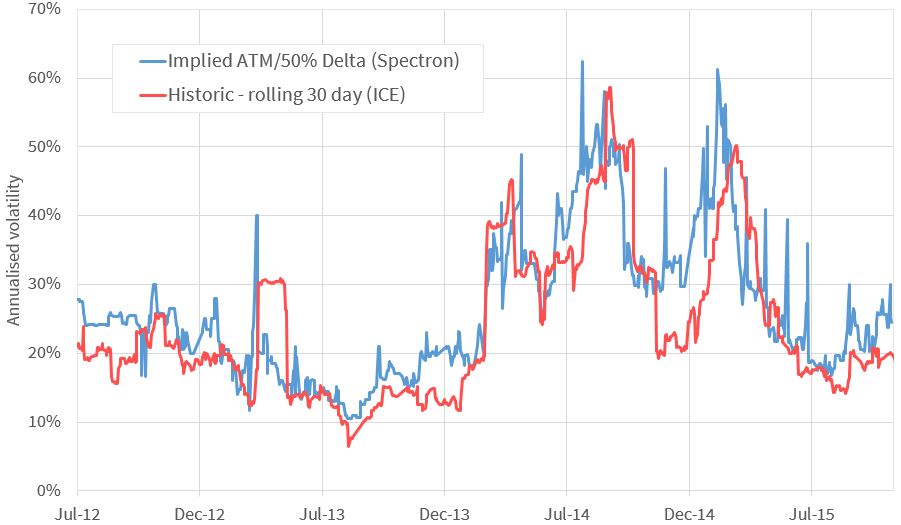

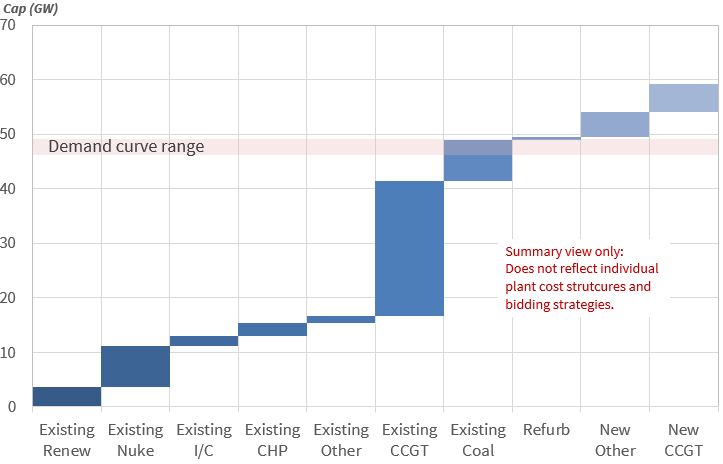

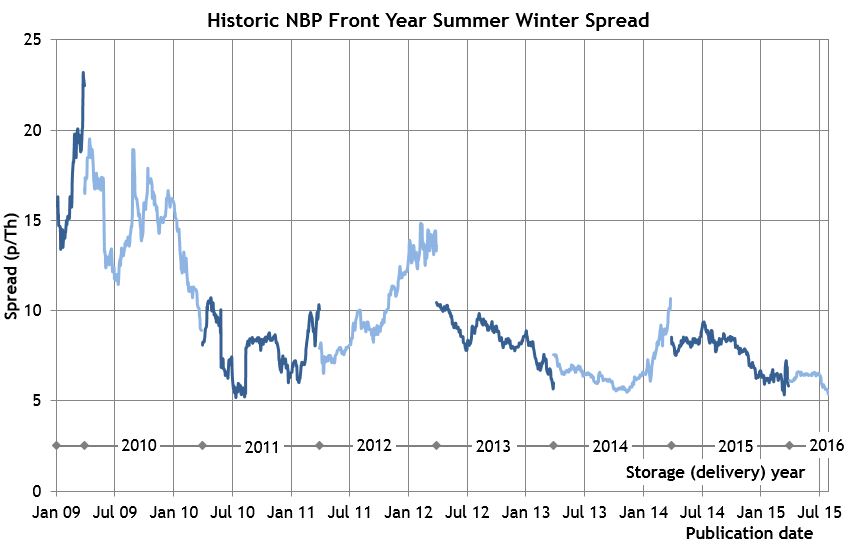

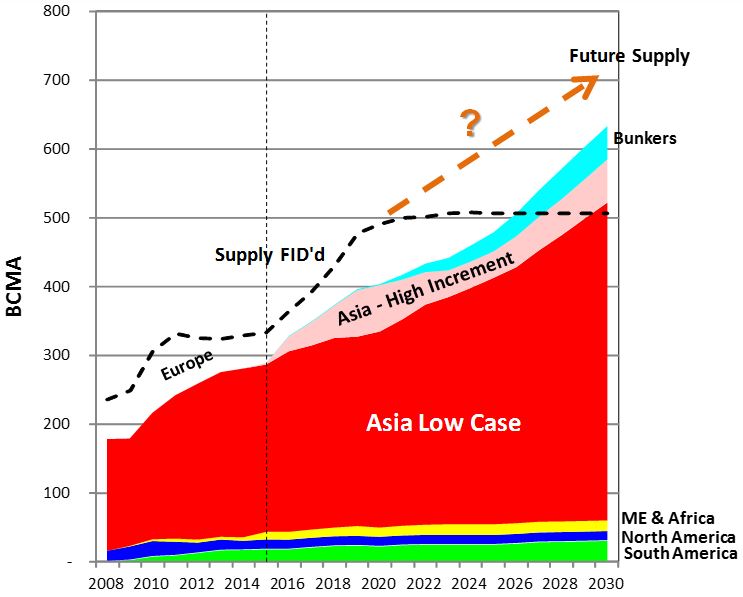

In an increasingly LNG-connected world, Russia’s strategic position is impacted by global gas market fundamentals. This is despite (or perhaps because of) Russia’s pre-eminent position in terms of gas reserves, export markets and productive potential. Chart 1 shows the global LNG balance from 2008 to 2030 in schematic fashion. The dashed line represents global LNG supply from existing and FID’d projects. The period to 2020 sees a huge increase in supply from the US, Australia and other projects. Asian demand in this timeframe is uncertain (Chinese economy and Japanese nuclear restarts in the main); the space between the Asian demand bar and the dotted line represents LNG which will flow to Europe.

Chart 1: Global LNG Balance

Source: Howard Rogers, OIES

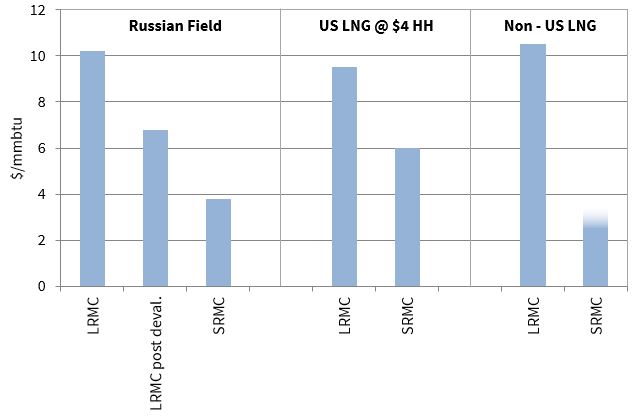

In the recent past Russia has dismissed the US shale gas boom as a short term, unsustainable phenomenon. Russia strategic focus has been pre-occupied with the long-running Ukraine transit imbroglio, frequent adaptations of its plans for South and North Stream pipelines and its response to the DG Competition inquiry. But Chart 1 suggests that the threat of a surge of European LNG imports has probably now become a ‘real and present danger’ to Gazprom’s European gas market share. On a cost basis, Gazprom’s supplies to Europe are very competitive as shown in Chart 2.

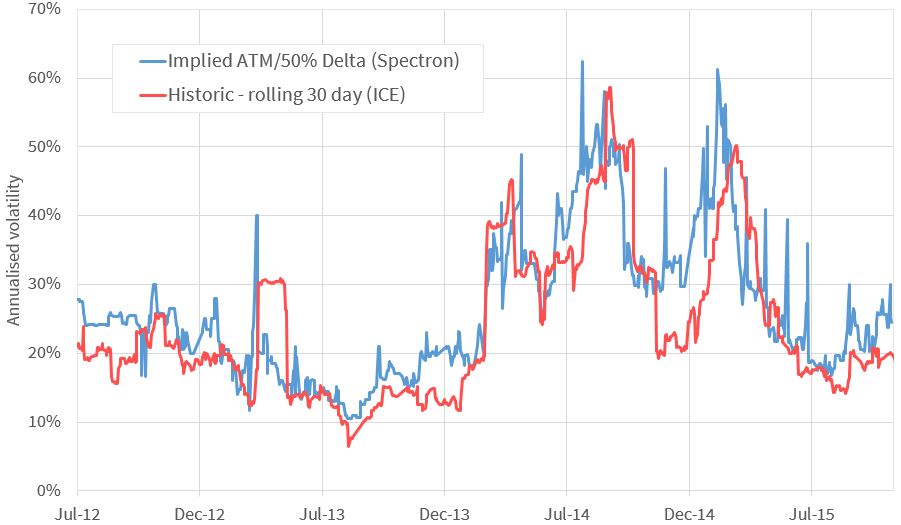

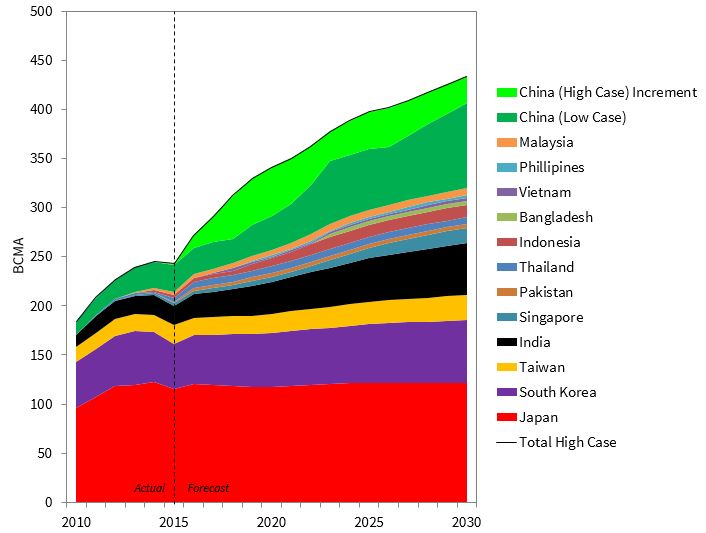

Chart 2: Comparison of Russian Pipeline Gas, US and Non-US LNG delivered to Europe

Source: J Henderson & D Ledesma, OIES

Chart 2 shows the long run marginal costs of ‘new’ West Siberian Gas in the range of $10/mmbtu (pre rouble devaluation) to $6.50/mmbtu (post rouble devaluation). But this is academic as it already has some 100 bcma developed which could flow to Europe border and cover variable costs and export tax at a border price of $3.80/mmbtu.

Once competing LNG projects are FID’d and committed however, they will flow at short run marginal costs of ‘Henry hub plus shipping and regas costs’ in the case of US projects and probably just shipping and regas costs in the case on non-US projects. Russian adherence to oil-indexed pricing to date has arguably encouraged competing LNG projects. Will it now adapt its price-volume strategy to limit further competition from new LNG?

How may Russia respond to lower prices and competing supply?

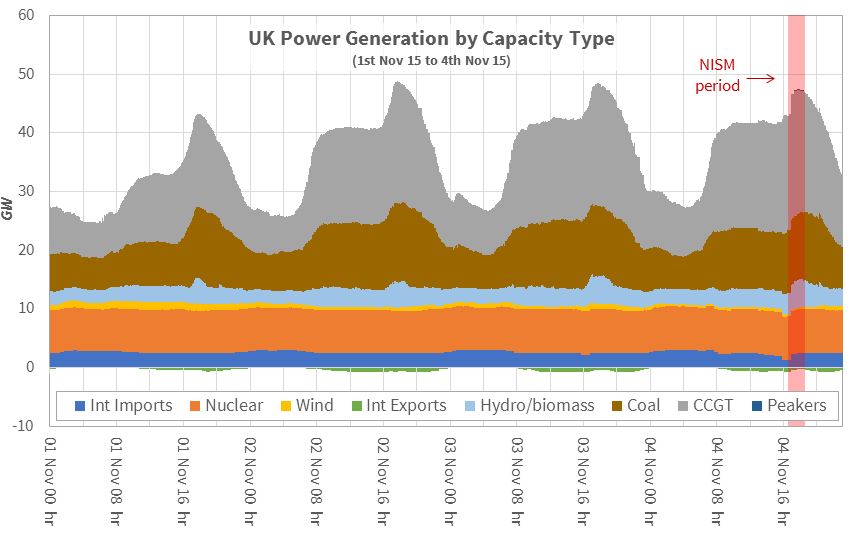

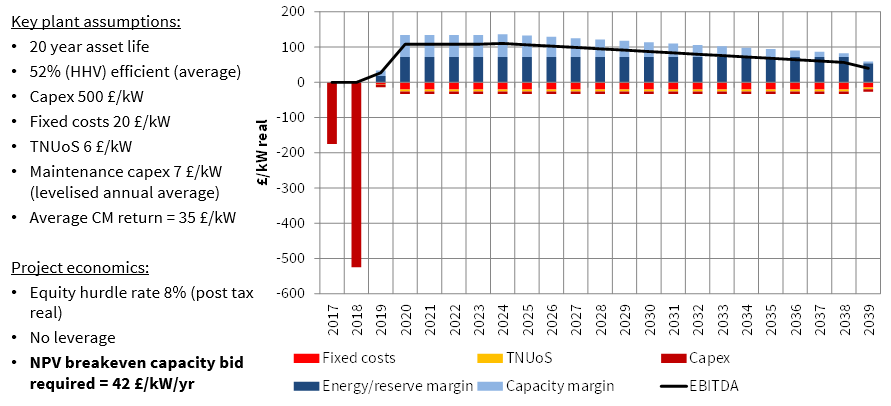

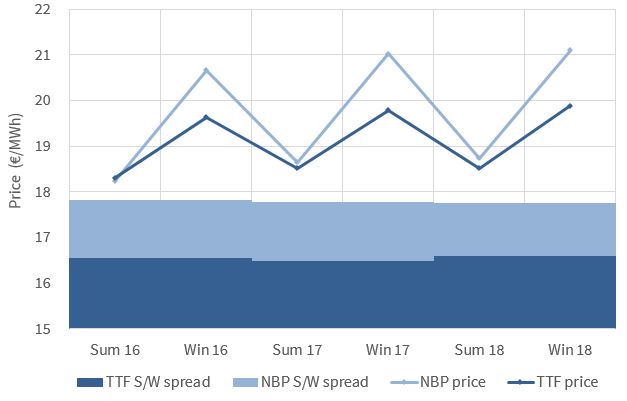

Gazprom has to date required its European mid-stream buyers to take delivery of (at least take or pay) contractual volumes at prices linked to oil-products. The majority of these contract volumes are delivered at border flange delivery points. Gazprom has however negotiated ad-hoc concessions and rebates relative to hub prices, to ease cost pressure on suppliers. This model is illustrated in the upper section of Chart 3.

Chart 3: Alternative Russian Contractual Sales Strategies

Source: Howard Rogers

Gazprom’s in-house marketing and trading capability gives it the option to pursue an alternative strategy in response to the emerging gas supply glut. The first logical steps would be:

- Move delivery points to the existing European gas trading hubs

- Move contract pricing terms to hub pricing

- Meet buyers’ nominations with a mixture of physical gas transported from West Siberia and gas bought off the hubs.

This is termed the ‘hub re-delivery model’ and is already used in UK medium terms contracts. It is depicted in the lower half of Chart 3.

In this manner Russia could influence the level of European hub prices through taking control of the scale of physical gas transported to the European gas market. Keeping European hubs (and by arbitrage Asian LNG spot prices) at prices below those supporting new LNG projects, acts to deter competing supply.

Over time the currently anticipated LNG ‘glut’ will be absorbed by a combination of Asian and new market LNG demand. Europe also faces the need to offset domestic production decline in Europe with new imports. As a result it is reasonable to expect European hub prices to rise again as these factors take effect into next decade. Gazprom then has another important strategic choice:

- If Gazprom allows European hubs to exceed $9 to $10/mmbtu, new LNG projects will achieve FID. Once new projects are launched, production SRMC is then very low.

- If Gazprom increases exports to keep European hubs below $9 to $10/mmbtu, new LNG FID’s will likely be delayed.

These dynamics leave Russia in a very strong position to dominate the sale of incremental gas supplies into Europe.

Pulling back to the bigger picture, it is worth noting that any idea on Russia’s part of compensating for disappointing European sales/prices by threatening to take its gas to Asia is flawed:

- Eastern Siberian gas is ‘stranded’, it is not connected by infrastructure to European markets,

- West Siberian gas delivered by the Altai line to China would be 30 bcma of the 100 bcma of ‘surplus productive capacity’; this would not impact deliveries to Europe,

- Additional supplies of Russian gas to Asian markets, whether pipeline gas or LNG, all other things being equal, merely displaces an equivalent volume of LNG from those markets which would likely end up in Europe.

As yet it is unclear whether Russia recognises the challenges set out above and is willing to adapt its strategy accordingly. But look out for changes in long term pricing terms and delivery points to hubs as the first signs of such a move.

Article written by Howard Rogers, David Stokes & Olly Spinks

Global LNG and European gas workshop

Timera Energy offers tailored workshops exploring the evolution of the global LNG and European gas market fundamentals and pricing dynamics. These workshops involve Howard Rogers who, as the Director of the Gas Programme at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, is acknowledged as a leading industry expert in the global gas market.

If you are interested in more details please email olly.spinks@timera-dev.positive-dedicated.net