The next two years are set to be an important period of transition for the European gas market. LNG imports are increasing as Europe adapts to its role as the global gas sink. In addition, oversupply at European hubs is eroding the traditional price setting role of oil-indexed Russian gas contracts. But as 2016 progresses and hub prices fall, there is clear evidence of evolving demand response from the power sector.

The European gas market is underpinned by a complex network of interconnected hubs, delivery routes and contractual obligations. In our view this undermines the effectiveness of traditional ‘field, flow & flange’ analysis to gain any sensible view of how market drivers interact to determine price dynamics.

A more practical approach is to focus analysis on the interaction between demand and the key tranches of flexible supply that set hub prices (e.g. Russian swing, flexible LNG and Norwegian production flex). We have previously set out how we do this using our analytical framework for European gas market analysis.

This approach has helped us to anticipate some of the major inflection points in European gas pricing over the last three years. For example the Summer 2014 price slump that marked the start of the current phase of oversupply and the ‘tipping point’ decline currently in progress as European prices fall towards Henry Hub support.

In today’s article we revisit this framework to set out our current view of the supply and demand balance in the European gas market. We also highlight a number of factors to watch in order to determine the evolution of market dynamics going forward.

European supply and demand balance: an annual view

There are two important considerations that can greatly simplify European hub price dynamics:

- Grouping sources of supply with similar pricing and flow dynamics

- Focusing on the flexible volumes of gas that drive hub pricing at the margin

The first of these tasks is helped by the fact that most sources of European supply are under long term contracts that use a similar structure. The second task is assisted by the fact that only a relatively small volume of total European supply actually has the flexibility to respond to changes in market price.

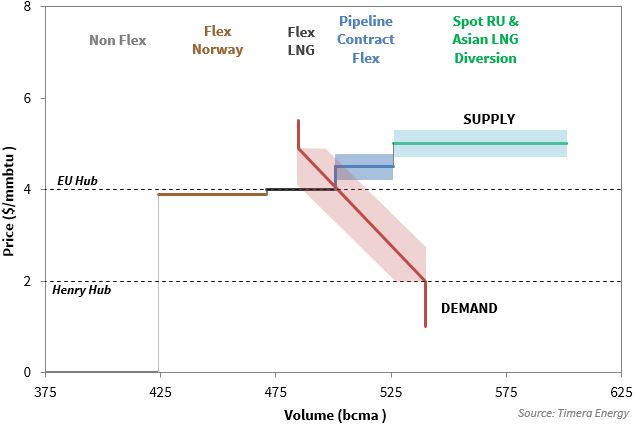

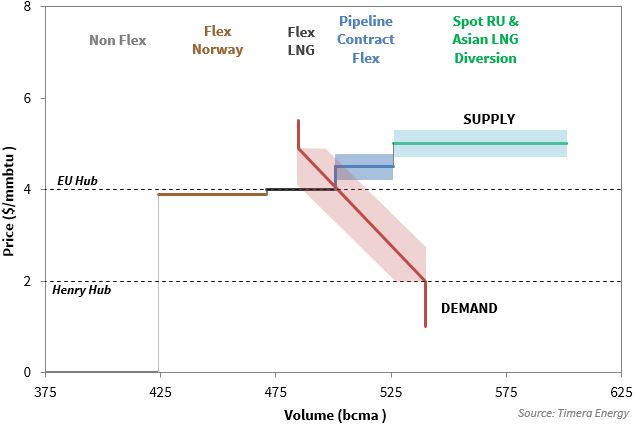

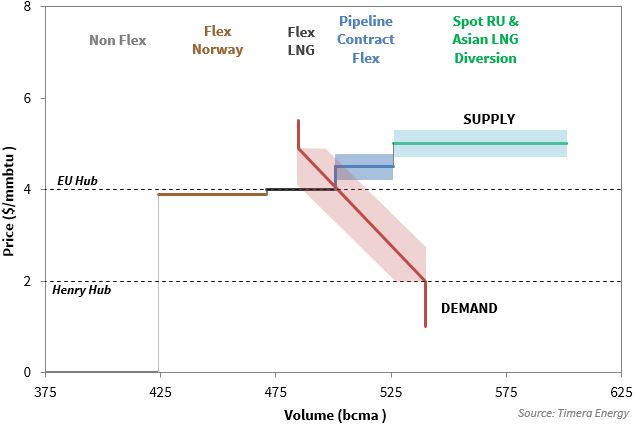

Chart 1 illustrates the current European supply and demand balance using this approach. It is important to note that the chart summarises supply and demand at an annual level. We come back below to some of the important within-year drivers of pricing and flows.

Chart 1: 2016 annual European supply and demand balance

Source: Timera Energy

Supply

The chart shows sources of European gas supply grouped into several key tranches:

- Inflexible price taking supply: consisting of (i) pipeline contract ‘take or pay’ volumes (ii) inflexible LNG contract volumes and (iii) domestic production (very low variable cost ). These ‘price taker’ volumes flow regardless of hub price levels.

- Norwegian flexible volumes: consisting of Norwegian production flexibility and flexible hub indexed contract volumes. These volumes are also effectively ‘price taking’ given Norway produces to an annual production target, but they are shown at a slight discount to current hub prices to reflect the fact that flows are optimised against hub prices.

- Flexible LNG volumes: made up of divertible European LNG supply contract volumes and LNG spot cargoes surplus to the requirement of other regions. Volume and flow depends on netback LNG spot price differentials relative to European hub prices.

- Pipeline contract flexibility: from predominantly Russian oil-indexed swing contract volumes above ‘take or pay’ levels.

- Spot Russian & incremental LNG: gas volumes that may be induced to flow into European hubs if prices rise sufficiently to attract (i) incremental Russian spot flows and (ii) diversion of LNG from other regions (predominantly Asia where fuel substitution is possible, typically to oil products).

The interaction between tranches 2, 3 and 4 and demand is the place to focus in order to understand price dynamics.

Demand

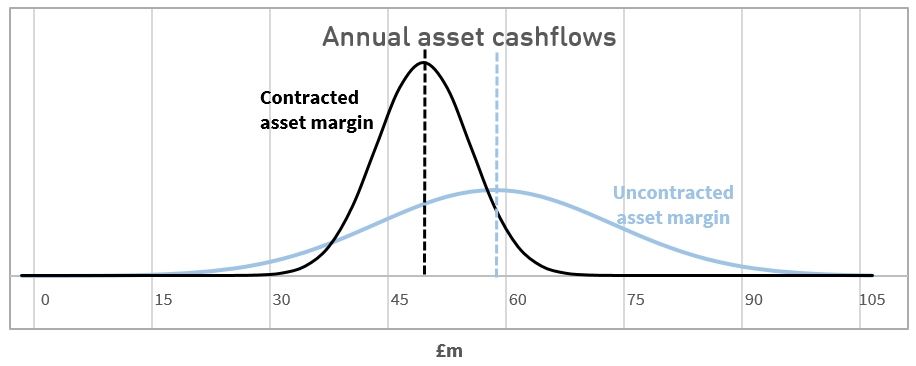

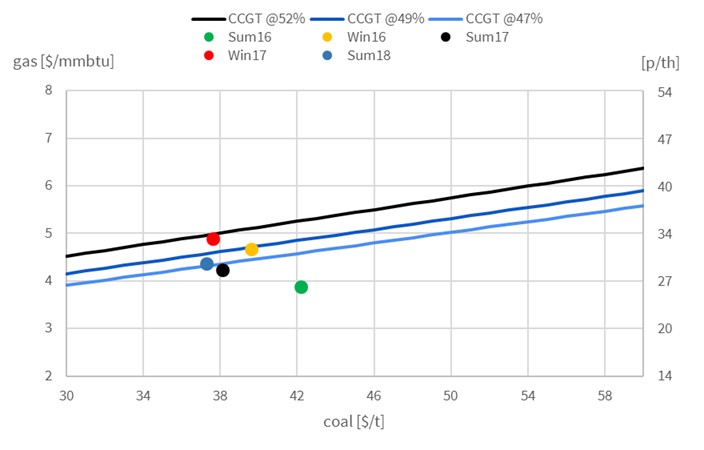

European gas demand is relatively price unresponsive in the shorter term, except for the power sector. The downward slope of the demand curve in the chart reflects the potential impact of coal to gas plant switching across European power markets as gas prices fall.

The amount of additional gas demand that is generated at lower hub prices depends on relative gas vs coal pricing. But there is 50+ bcm of switching potential if coal prices remain relatively stable while gas hub prices continue to decline towards Henry Hub. We will come back in a subsequent article to explore this dynamic in more detail, but it is going to be a key factor driving gas market dynamics over the next 2-3 years.

Pricing at the margin

Declining hub prices in 2016 are being driven by a battle to place Norwegian flex, LNG imports and Russian pipeline volumes across European hubs. This is in addition to the large volume of ‘must flow’ gas shown at zero price in the chart.

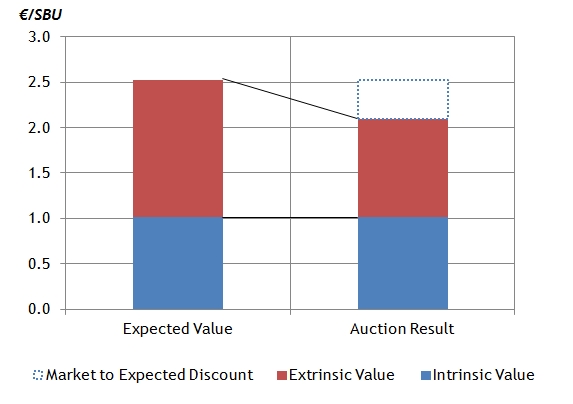

Oil-indexed contracts have historically played an important role in setting hub prices at the margin (the intersection of supply and demand). Oil-indexed prices tend to act as a magnetic force given the use of swing gas to balance the market. But as 2016 progresses into 2017, the impact of the tipping point we foreshadowed this time last year looks set to gather momentum.

A combination of robust production flows (particularly from Norway) and rising LNG imports are pushing oil-indexed contract prices off the margin. The result is that hub prices (currently around 4.00 $/mmbtu) are falling below oil-indexed contract benchmarks (4.50+ $/mmbtu). With hub prices at a discount to contract prices, suppliers are incentivised to reduce contract volumes to take or pay levels.

The damage to hub prices is being caused by increasing volumes of supply being pushed in to the European market to left of the margin. Robust production levels and rising LNG imports are forcing the supply curve down the demand curve to clear the market at a price level which induces an adequate volume of power sector demand response.

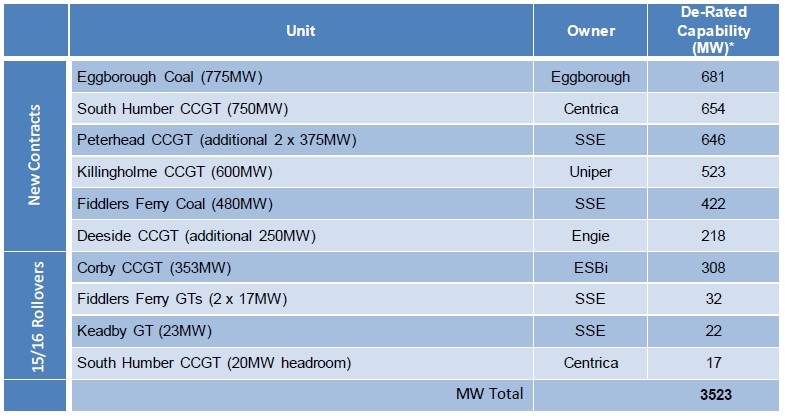

For evidence of this look to the UK and Italian power markets. CCGTs are the dominant form of generation in both markets and load factors have increased significantly across the last 6 months as gas prices have fallen. Peak clean spark spreads in other Continental power markets have also recovered, foreshadowing the potential for a much higher volume of switching if hub prices continue to decline.

Within-year dynamics

For the purposes of this article we have shown an annual view of supply and demand to summarise high level drivers of hub pricing. But behind this our analytical framework allows us to drill down into a number of more complex factors that determine how the market clears on a within-year basis. These are worthy of a separate article but we provide a brief summary here to highlight their role:

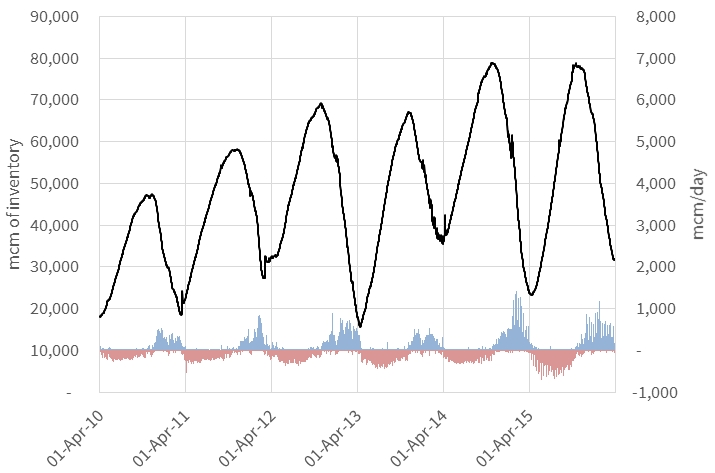

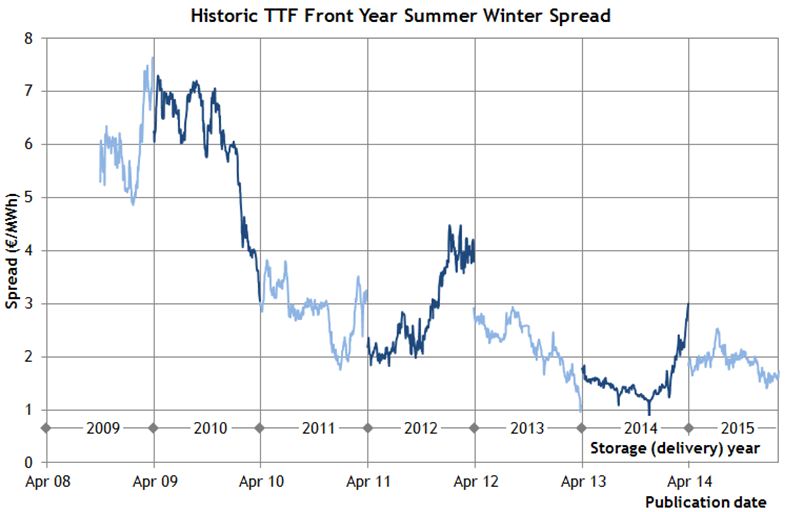

- Gas storage plays a key within-year balancing role, both seasonal and to dampen shorter term price volatility. The influence of storage is largely netted out at an annual level (hence its absence in the chart) but it remains a key driver of pricing dynamics at a sub-annual level.

- Norwegian production flows have a pronounced seasonal profile (higher in winter) and are optimised by Statoil on a day to day basis across their different hub access delivery points.

- Take or pay profiling of oil-indexed contract volumes is driven by the relative relationship between hub and contract prices across the year (with suppliers incentivised to take gas when it is cheapest based on a 6-9 month oil price lag).

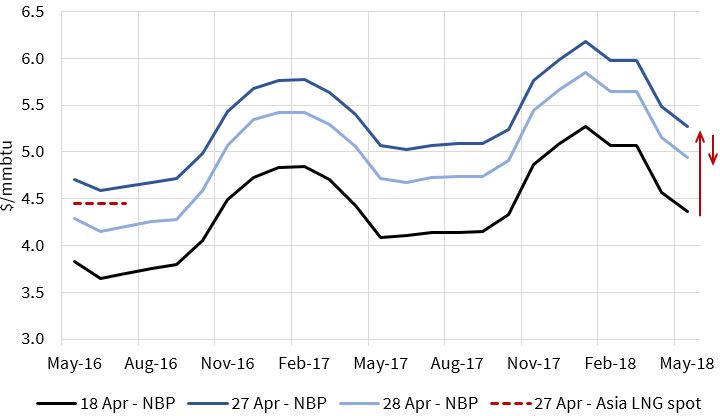

- LNG imports can ebb and flow into European hubs based on short term fluctuations in global spot prices.

- Weather can have a significant influence on gas demand. This was illustrated by very low 2014 gas demand due to unusually mild winter.

While these factors increase the complexity of the supply and demand balance at any point in time, they do not materially erode the relevance of the annual level view shown in Chart 1.

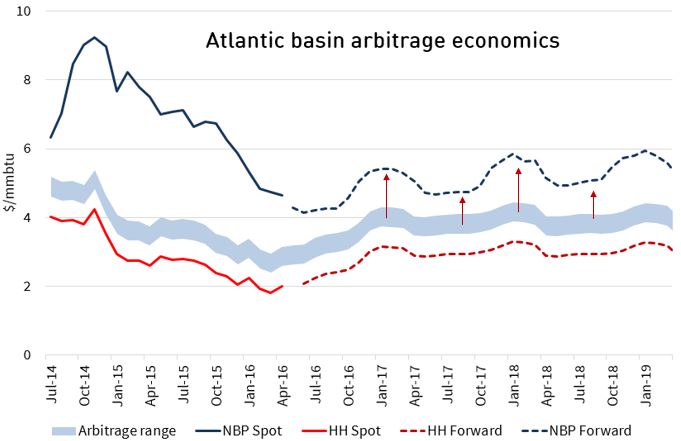

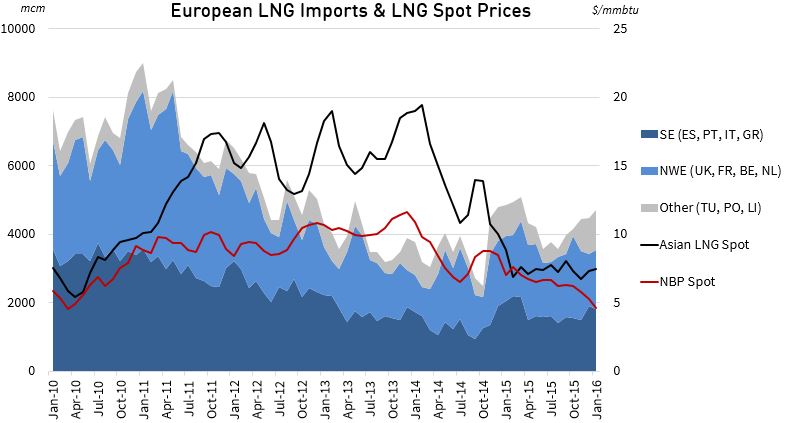

Looking forward, the US market looms large below

A key unknown variable remaining across the next two years is the level of surplus LNG Europe will need to absorb as new liquefaction projects ramp up production, against what appears so far to be a backdrop of weak Asian demand. There has been a noticeable increase in LNG flow into North West European hubs over the last 12 months as we showed last week. But this volume is small relative to an anticipated 23 bcm ramp up in new LNG flow into the global market across 2016 and 35 bcm in 2017.

There have however been some notable delays in production from new liquefaction projects e.g. Gorgon and Sabine Pass. It should also be recognised that trains often take 6 months or so to achieve 90% of nameplate capacity, so there is a lag to take into account (as well as the ongoing poor performance of some established LNG suppliers).

The Asian LNG spot price differential above European hubs is a barometer for how much of this new LNG may flow into Europe. That spread is currently approaching zero. That means Europe is the most attractive place to send surplus cargoes, LNG that as it is absorbed will place downward pressure on hub prices.

This is why we expect coal to gas switching dynamics to attract much more focus as 2016 develops. The importance of the role of switching is not widely understood. As the influence of oil-indexed contract pricing is eroded, the supply side of the European gas market is set to become increasingly dominated by price insensitive volumes of supply (inflexible production, Norwegian flows and LNG imports). This shifts the market focus to demand response and the relative variable costs of CCGTs versus coal generators.

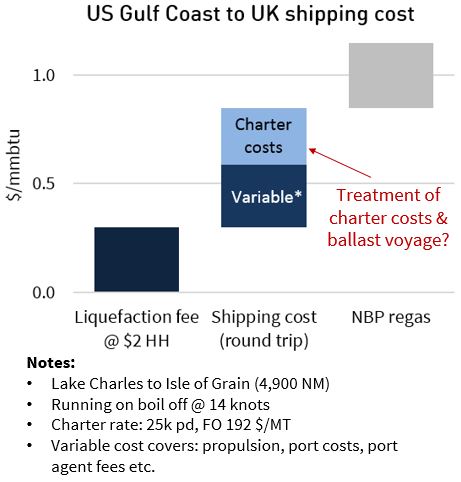

As oversupply increases, the other source of European hub price support comes from across the Atlantic. If hub prices continue to decline, US exports will be ‘shut in’ on a variable cost basis. We estimate shut in to occur at a Henry Hub to NBP/TTF spread between 0.5-0.8 $/mmbtu, the sum of variable liquefaction, shipping and regas costs. The cost range depends on the extent to which off-takers have committed to shipping and regas capacity on a medium/long term contractual basis, in which case it is a ‘fixed’ cost. But regardless of shut in dynamics, US export volumes remain small until 2018.

Beyond coal-gas switching in the power sector, further support for European hub prices could derive from Russia relaxing its contract take or pay levels with European contractual buyers. This would take physical gas ‘out of the system’ and help the market to clear. However if this does not happen it is possible that European hubs could converge with Henry Hub.

In this situation the ultimate source of European hub price support is the diversion of surplus global cargoes to the US market instead of Europe. Don’t laugh … it happened during the last global glut in 2009. In a bitter irony for US exporters, this could mean a period of reemergence of US imports at the same time new US liquefaction capacity is being commissioned.

Article written by David Stokes, Olly Spinks and Howard Rogers

Global LNG and European gas workshop

Timera Energy offers tailored workshops exploring the evolution of the global LNG and European gas market fundamentals and pricing dynamics. These workshops involve Howard Rogers who, as the Director of the Gas Programme at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, is acknowledged as a leading industry expert in the global gas market.

If you are interested in more details please email olly.spinks@timera-dev.positive-dedicated.net