The article below is our last before the summer break. We will be back with more in late August.

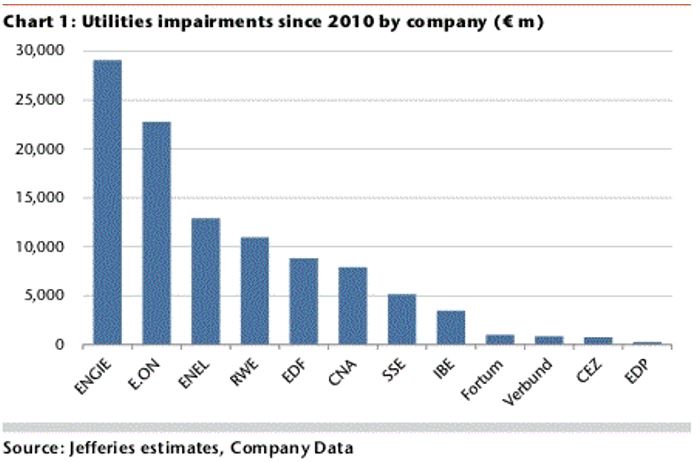

Three weeks ago we set out the case for an unprecedented sale of conventional supply assets by European utilities. French and Italian utilities alone have announced their intention to sell upwards of €30 bn of assets. And this is only part of a larger pool of assets earmarked for sale across Europe, as utilities & producers shift their strategic direction and respond to balance sheet constraints.

The sheer scale of asset sales should open up substantial value opportunities, as well as paving the way for new entrants. Value is supported by a lack of utility buyers and cyclically depressed conditions in some markets. But potential buyers face the challenge of finding & pricing undervalued assets, while avoiding assets that are in terminal value decline.

In this week’s article we set out our view on two specific value opportunities:

- Gas-fired power assets

- Mid-stream gas assets

We focus on these because we see structural market changes that support value and offer asymmetric upside. But a robust investment case does not need to be based around a bet on a broader recovery in asset values. Ultimately value creation comes down to buying well chosen assets that are play a structural role in market operation… at the right price.

Value opportunity 1: Gas-fired power assets

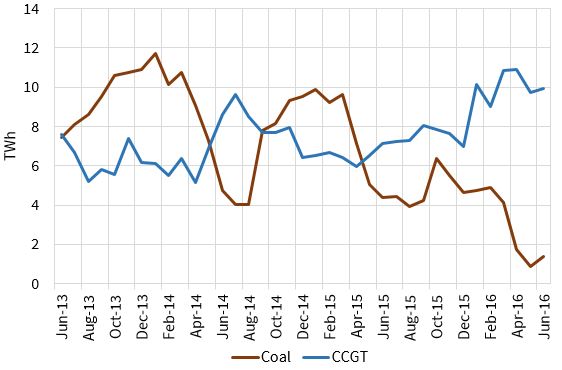

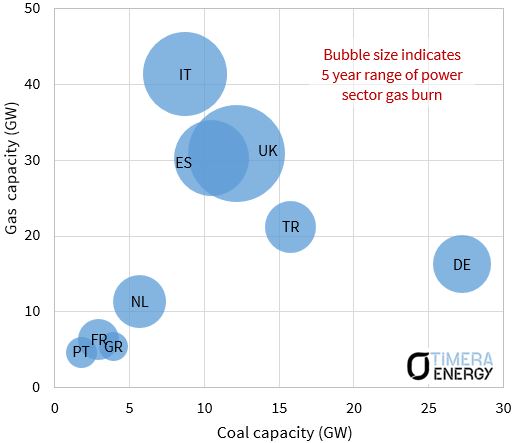

European gas plant values have been decimated this decade. This has happened against a backdrop of general overcapacity in European power markets, caused largely by post financial crisis weakness in power demand growth and capacity overbuild. But beyond this, gas plants load factors and margins have suffered specifically from:

- Renewables: The erosion of load factors & prices by rising low variable cost renewable generation

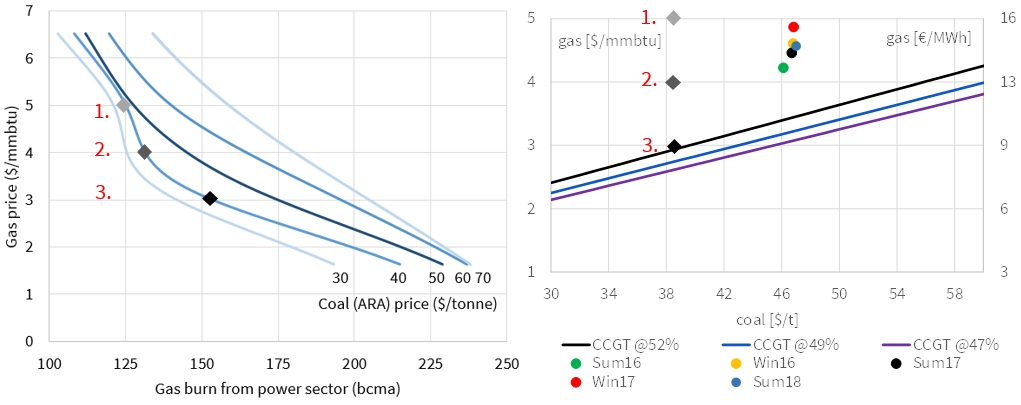

- Cheap coal & carbon: Relatively weak coal and carbon prices have favoured coal plant competitiveness over gas plants.

The consensus view amongst utilities is for more of the same. But this ignores some key structural drivers that support a recovery in gas plant load factors, summarised in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Value thesis on European gas-fired power plants

| Asset class: | Gas-fired power assets | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Asset types: | CCGT, CHP, gas peaking plants | ||

| Status quo: | Load factors, margins and asset value have been eroded by cheap coal, increasing renewable output and low carbon prices. | ||

| Value thesis: | |||

|

|||

| Sellers: | Potential buyers: | ||

| European utilities | Funds (infra, PE), smaller utilities/producers | ||

Case study: Continental CCGT assets:

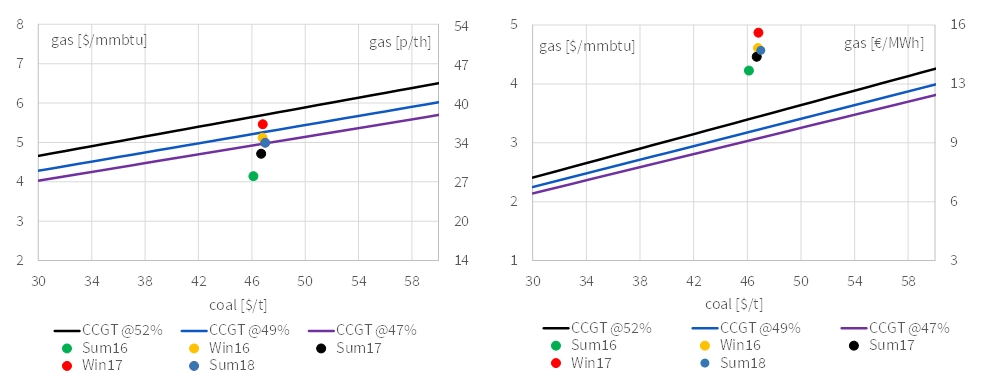

CCGTs in Continental European power markets are widely regarded as value toxic. In many cases this is justified. A number of older, less flexible and/or locationally disadvantaged gas-fired assets are ripe for closure. Even owners of brand new merchant CCGTs in markets such as Germany and the Netherlands are suffering from several years of negative cashflows. Buying assets like this based on the thesis of a sparkspread recovery in the 2020s takes quite a specialised investor risk/return profile.

To build a more stable investment case it is important to target assets that have access to revenue streams that can ‘top up’ wholesale energy margin to cover fixed costs. This incremental revenue can come in the form of capacity payments, balancing & ancillaries revenue or pre-contracted revenue streams (e.g. CHP steam and onsite power contracts). There are also structural factors protecting plant energy margins in some markets e.g. the price setting dominance of CCGTs in UK and Italy and the requirement for gas-fired peaking capacity in Belgium and France.

But covering fixed costs is about buying time for value recovery. There are three important structural shifts taking place that support value upside:

- Capacity payment mechanisms are in the process of being implemented across Europe, adding an additional source of revenue that should rise as market capacity balances tighten.

- Regulatory driven closures of large volumes of coal and nuclear plants across Europe should increase gas plant load factors and margins in the early to mid 2020s. A number of existing newer/flexible CCGTs are set to become key for security of supply as this happens.

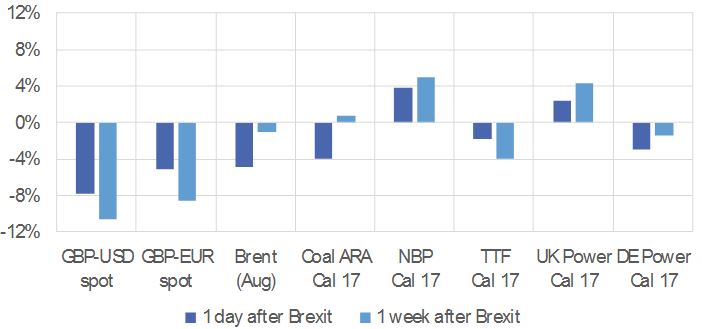

- Gas plant competitiveness is improving again as the global market transitions into a period of structural oversupply and gas prices fall. This may be further supported by actions to increase the EU carbon price signal (e.g. the French proposal to implement a carbon price floor).

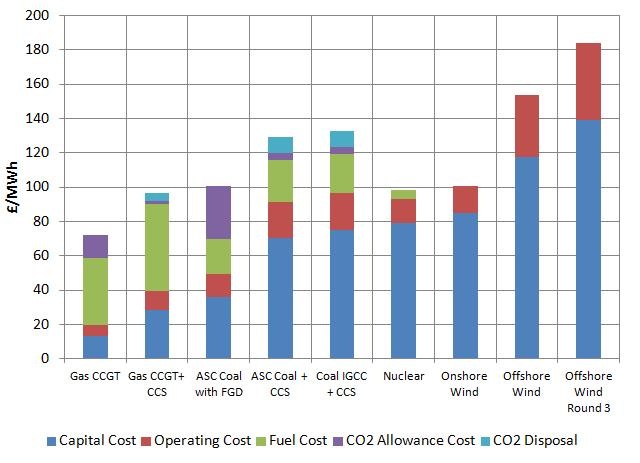

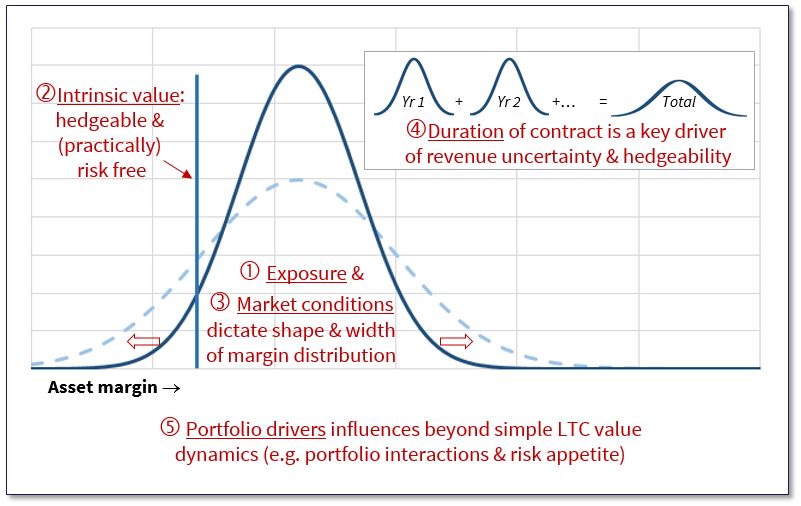

Relatively new assets that will be critical for security of supply in the 2020s can be bought for a fraction of new build cost (e.g. 15-20%). But the premium that owners pay for access to value upside includes plant fixed costs. The challenge in buying Continental CCGTs is ensuring protection from negative cashflows, while understanding and pricing the risk/return distribution of assets.

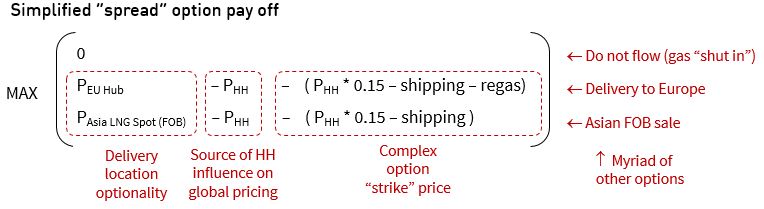

Value opportunity 2: Midstream gas assets

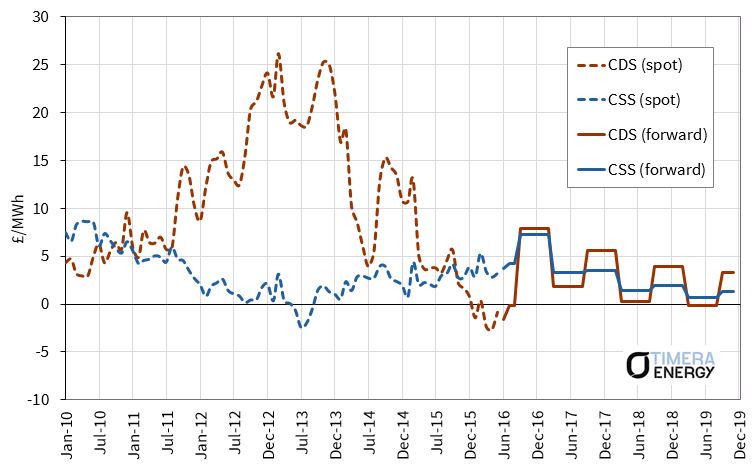

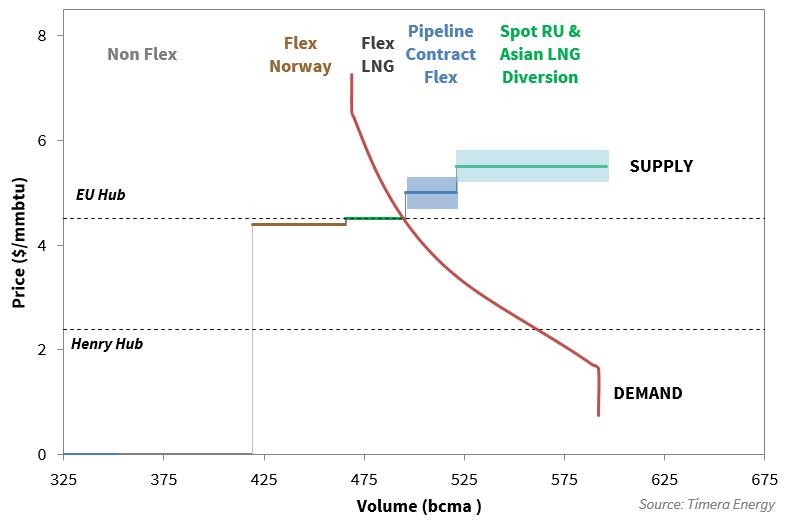

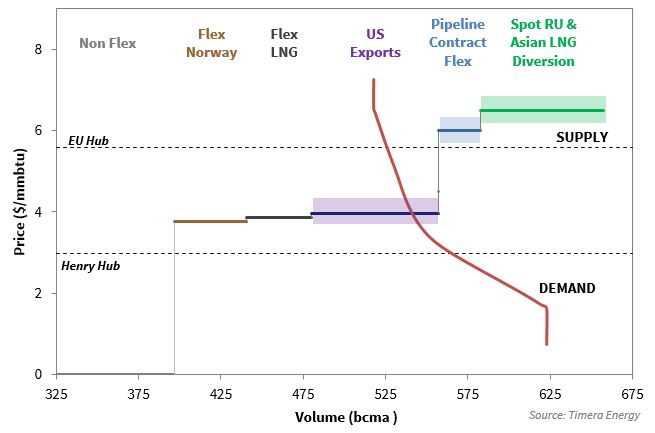

The value of midstream gas assets (e.g. pipelines, gas storage & LNG regas terminals) has also suffered this decade. Weak gas demand has been a big factor behind this, particularly as a result of declining CCGT load factors (for the reasons set out above). There are two key price signals for midstream supply flexibility value:

- Price spreads: the signal for the value of supply flexibility e.g. seasonal spreads for storage, locational spreads for pipelines.

- Prompt price volatility: the signal for the prompt deliverability of gas e.g. in response to demand swings or supply disruptions.

Both price signals have declined to historically low levels this decade, falling from levels that support investment in new gas storage assets, to levels that are forcing the mothballing and closure of existing flexible assets. The consensus view among utilities is again for a continuation of current market conditions.

Table 2: Value thesis on European midstream gas assets

| Asset class: | Midstream gas assets | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Asset types: | Gas storage, gas pipelines, LNG regas terminals | ||

| Status quo: | Asset pricing reflects current historically weak market price signals for gas supply flexibility (price spreads and price volatility). | ||

| Value thesis: | |||

|

|||

| Sellers: | Potential buyers: | ||

| European gas utilities; oil and gas producers | Funds (infra, PE), producers, LNG players | ||

Case study: Faster cycle gas storage assets:

Midstream gas assets have traditionally sat in utility portfolios. But as utilities refocus strategy and sell supply assets, the midstream transaction flow is increasing.

The value upside story for midstream gas assets is driven by a structural transition in the European gas market. As domestic gas production declines, Europe is becoming increasingly reliant on importing gas from outside its borders (e.g. via LNG and Russian gas), creating an associated midstream flexibility requirement. A growing requirement for gas-fired plants to backup renewable intermittency is also set to flow through into higher demand for gas supply flexibility.

This is happening against a backdrop of ageing infrastructure. An estimated 5% of European storage capacity has been closed this decade. The future of a number of other storage facilities is threatened by market price signals that do not cover renewal capex costs (most prominently the large Rough storage facility in the UK).

A feature of midstream assets that makes them attractive to investors is low fixed costs. The overheads and maintenance costs for pipelines and storage assets are typically a fraction of those for power plants. This means that good assets (e.g. that play a structural role in supporting security of supply or portfolio risk management) are likely to retain positive cashflow as owners wait for value recovery.

Challenges in getting the deal done

In a low yield investment environment, infrastructure investors are increasingly interested in European energy assets. The investment thesis around some asset classes has attracted a widening interest, with asset pricing starting to reflect this (e.g. UK CCGTs and peakers which we have written about now for several years).

However other classes of assets in the utilities sales queue are less well understood e.g. Continental CCGTs and midstream supply assets. In our view these may now offer better value and more competitive transactions price opportunities. But there are three key challenges in building a watertight investment case.

The first challenge is finding some form of downside protection to cover asset fixed costs, while maximising access to value upside (ideally of the asymmetric variety). Upside does not need to be a bet on a broader market recovery but can be built around specific asset benefits (e.g. location, flexibility or barriers to competition). The assessment of the ‘tail value’ of asset margin distributions plays an important role here.

The second challenge is quantifying asset risk/return distributions in order to define a risk adjusted valuation. A robust valuation is built on an understanding of the interaction between the risk/return dynamics of different revenue streams. Infrastructure investors are likely to feature strongly as potential buyers (albeit in partnership with utilities/producers as offtake counterparties). This fragmentation in ownership is likely to require new contracting and business models to support value monetisation and asset operation.

The third challenge is transaction price, given asset value is ultimately a function of price paid. This is where gas-fired plants and midstream supply assets are a particularly interesting prospect. Current pricing appears to reflect an overhang of assets for sale, set against a relatively small pool of potential buyers. That swings negotiating power in favour of asset buyers.

Article written by David Stokes and Olly Spinks