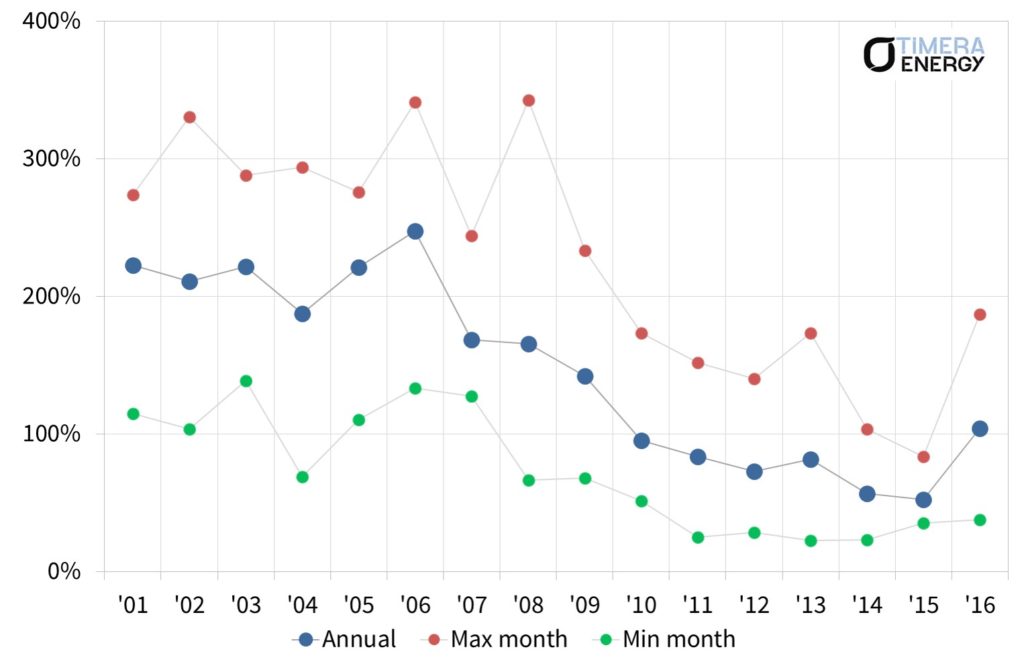

After 5 tough years, a glimmer of hope emerged for gas storage operators in 2016. Spot price volatility at European hubs started to show signs of a more enduring recovery. This has been supported by a resurgence in power sector gas demand. Reductions in existing gas supply flexibility have also helped, for example constraints around the UK’s Rough storage facility.

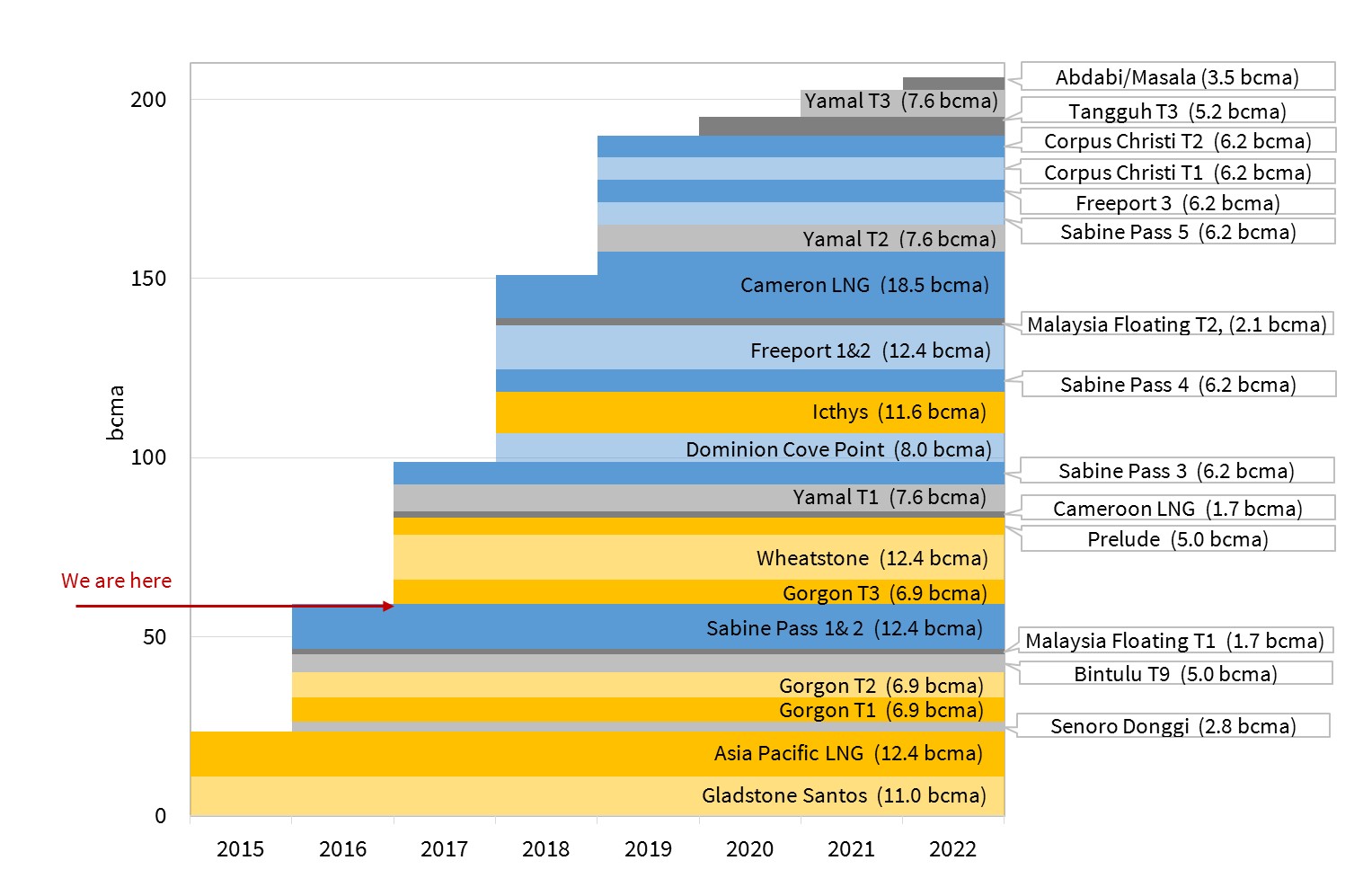

However gas storage facilities face a potential threat in the form of rising LNG imports. There is little doubt that LNG import volumes into Europe will increase significantly over the next decade, as the LNG supply glut intensifies and European import dependency increases. But there is less clarity as to exactly how rising LNG imports will impact hub price volatility.

The simple argument that is often presented is that LNG regas terminals and on-site tank storage compete with conventional gas storage facilities to dampen volatility. But this argument ignores some important practical constraints that limit LNG import flexibility.

Deconstructing LNG import terminal flexibility

LNG import flexibility can be broadly split into two categories, the first associated with the LNG supply chain and the second with regas terminal storage tanks:

- ‘Type A’ flexibility – LNG cargo diversion: Cargoes not initially intended for European delivery are sent to Europe as a result of (i) cargo diversion or (ii) purchase of spot cargoes. Or alternatively cargoes that were intended for Europe are diverted away.

- ‘Type B’ flexibility – use of LNG terminal storage: On-site tank storage can be used to profile gas send out in response to hub price volatility (i.e. increased/decreased withdrawal as prices rise/fall). Tank storage can also facilitate “Type A flex” via enabling the reload and diversion of cargoes that are bound by destination specific contract clauses.

Let’s consider how each of these sources of flexibility impacts hub price volatility.

Type A flexibility constraints: diversion flexibility

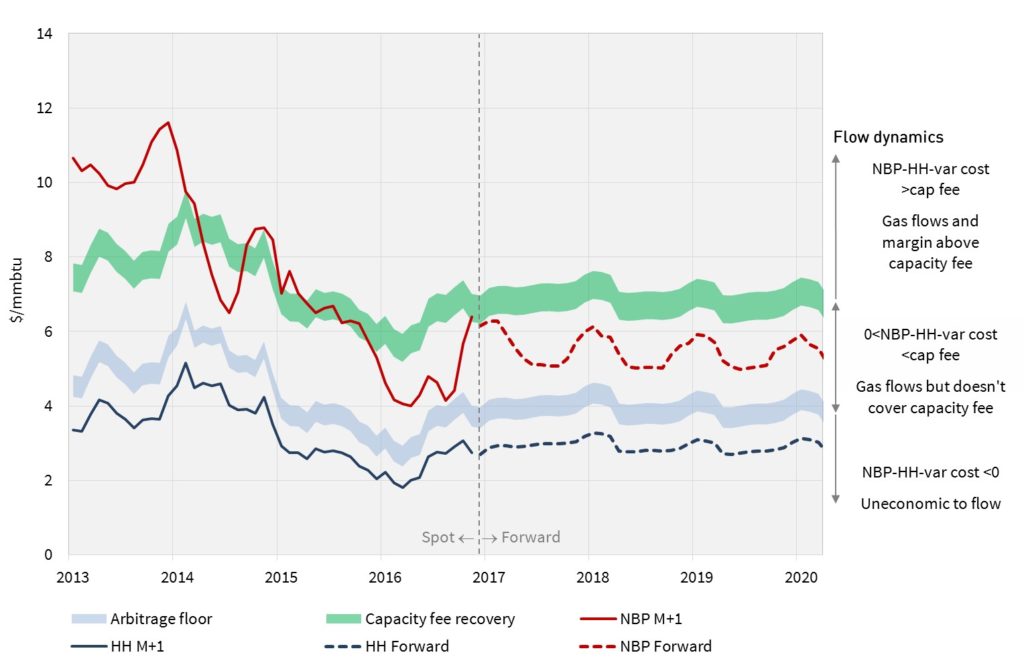

The LNG supply chain can certainly provide seasonal flexibility to the European gas market, if there is an adequate hub price signal to incentivise a seasonal flow profile. However there are practical constraints around the ability of LNG imports to respond to spot price volatility.

Spot price volatility is by nature a short term phenomenon, often shorter than the time horizon required for LNG supply chain response (e.g. 1 to 3 weeks). Response time depends on the availability of divertible LNG cargoes which can be constrained by price, location and contractual factors.

Ability to divert a cargo in response to higher hub prices may depend on the availability of short term shipping and regas capacity. Diversion or reloading LNG in response to lower hub prices often relies on complex diversion economics and logistics and access to regas terminals.

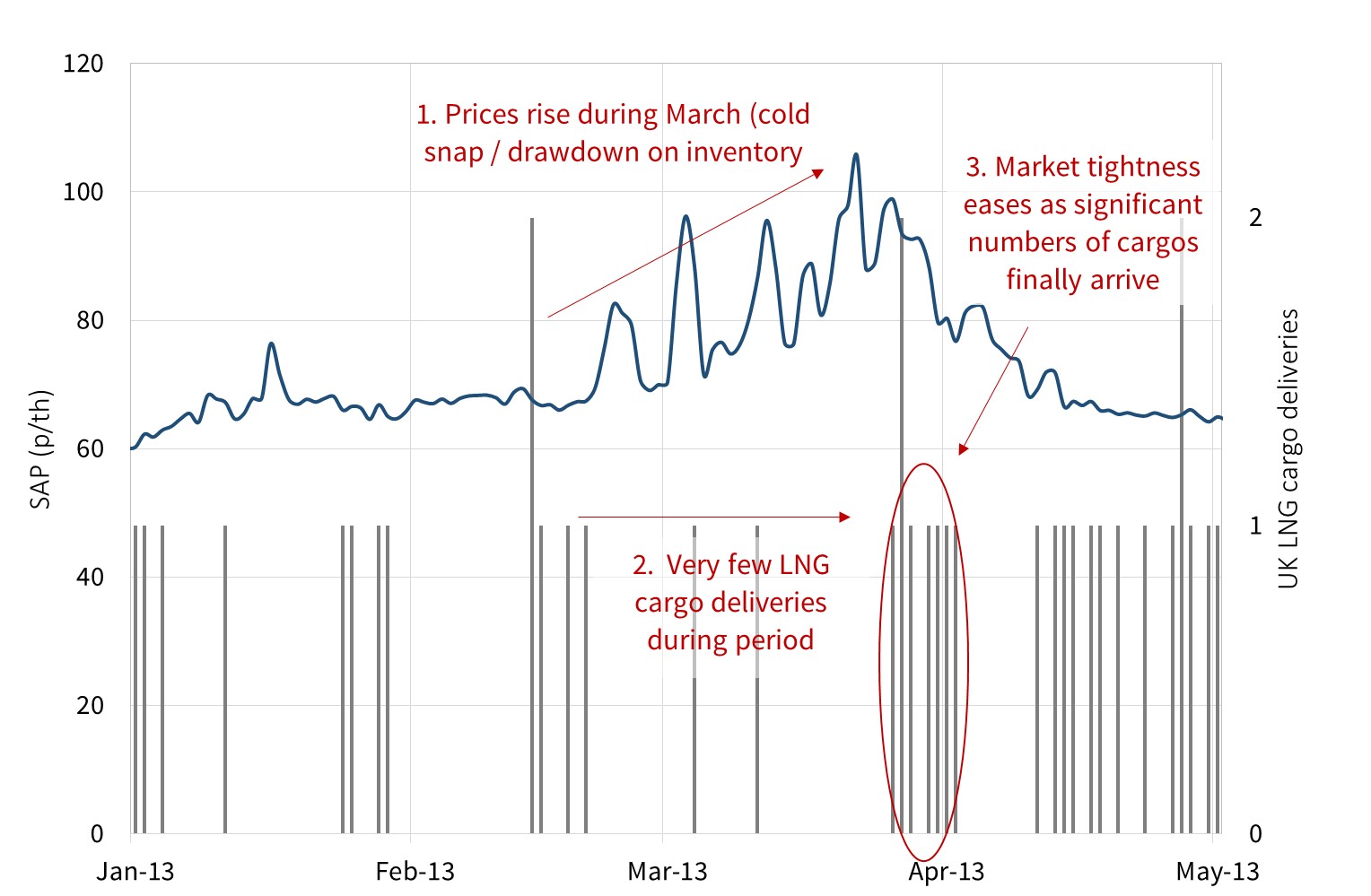

Chart 1 shows a case study focused on the response of LNG imports to the UK NBP price spikes in Mar-Apr 2013.

Chart 1: UK LNG deliveries vs spot prices (Jan – Jul 2013)

Source: Timera Energy (data from National Grid)

Hub price volatility across this period was caused by a combination of major infrastructure outages that curtailed Norwegian imports, cold weather and issues with the IUK interconnector. Spot prices began to signal system stress in late Feb and remained at elevated levels throughout Mar (spiking to above 100 p/th). But it was not until Apr that the LNG supply chain was able to deliver a significant increase in import volumes to help rebalance the system.

Type B flexibility constraints: regas tank flexibility

At first glance, LNG tank storage may appear to have similar characteristics to fast cycle gas storage facilities. But while tanks can be used to profile gas send out, there are fundamental differences that limit regas terminal flexibility. These include:

- LNG storage can only inject into the network, not withdraw from it

- During periods of high terminal utilisation, storage tank optimisation is restricted by a requirement to send out gas to facilitate the unloading of cargoes

- Minimum inventory requirements to keep the tanks cool can constrain send-out during periods with few deliveries

- The use of terminal storage can often be limited by contractual terms

- In tank boil off rates contribute to the cost of holding inventory, although rates are relatively low (0.02-0.1% per day)

Under the right conditions, regas terminal send-out can be profiled into periods of higher prices to dampen volatility. But the factors listed above combine to substantially reduce the flexibility associated with terminal tank storage.

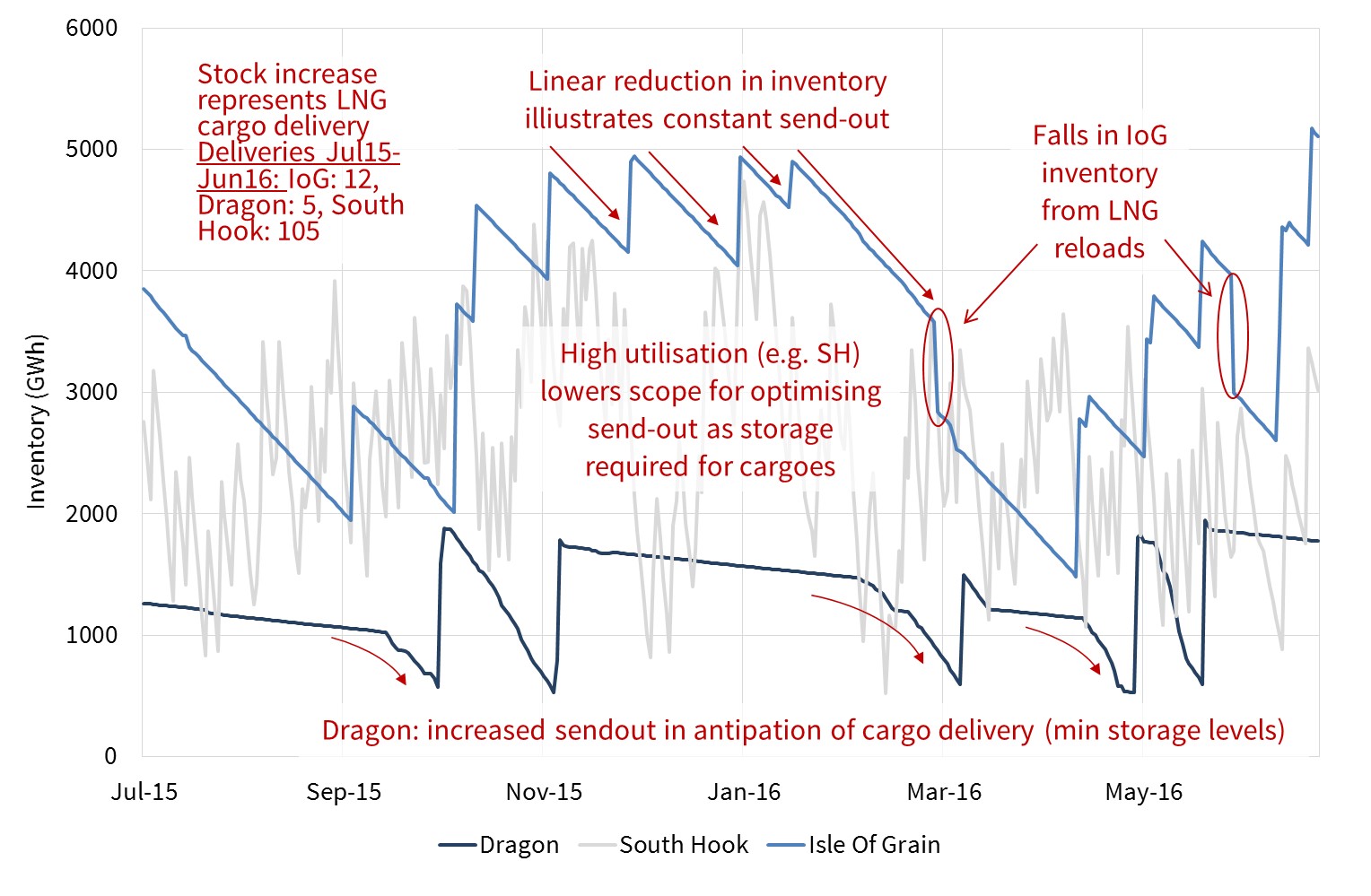

Chart 2 shows a case study of UK terminal send out over a recent 12 month period to illustrate the fact that physical terminal constraints and cargo logistics are key drivers of terminal send-out, as opposed to optimisation against NBP spot prices.

Chart 2: UK regas terminal send-out (Jul 2015 – Jun 2016)

Source: Timera Energy (send-out data from National Grid)

The chart shows how tank inventory was typically sent out in a linear (steady) profile, as opposed to being optimised against spot price volatility. It also illustrates how terminals need to use high send out rates during periods of higher utilisation (e.g. for South Hook receiving regular cargoes). Terminals with lower utilisation such as Dragon need to retain a minimum inventory to keep the tanks cool and then typically send out gas in anticipation of a new delivery.

LNG imports as a source of higher volatility?

There is inherent flexibility within the LNG supply chain to divert cargoes to higher priced markets. Regas terminal storage tanks also provide flexibility to profile send out of inventory. But the combination of these two factors alone does not necessarily mean that rising LNG imports will act to dampen European hub price volatility.

There are circumstances under which rising European dependence on LNG imports may act to increase spot price volatility. This is particularly the case because of the growing role of European hubs as the global LNG swing market (or ‘market of last resort’). Consider the following two cases:

-

- Surplus: During periods of surplus LNG cargoes, Europe can see a substantial ramp up in imports. Periods of high terminal utilisation can act to temporarily depress hub prices. This dynamic is exacerbated by the fact that LNG cargo volumes are bulky in nature relative to other supply sources delivering to hubs (e.g. fields, pipelines, storage).

- Shortage: Relatively large volumes of LNG supply can also be diverted away from Europe during periods of tightness in other regional markets (e.g. Asia or South America). This can drive up European hub prices, particularly if hubs need to ‘price up’ to compete for available cargoes.

Swings from surplus to shortage can occur over a relatively short time span, given the immaturity of the LNG spot market (e.g. compared to the crude market). So cycles of surplus and shortage can act to drive higher European spot price volatility.

The logic that rising LNG imports always acts to reduce spot price volatility oversimplifies the problem. The reality is more complex and depends on market conditions. If conditions are right, terminal send out can be profiled to dampen hub price volatility. But this effect is likely to be overshadowed by a structural increase in volatility as Europe evolves into the role of ‘shock absorber’ for the LNG market.

Article written by Olly Spinks and David Stokes