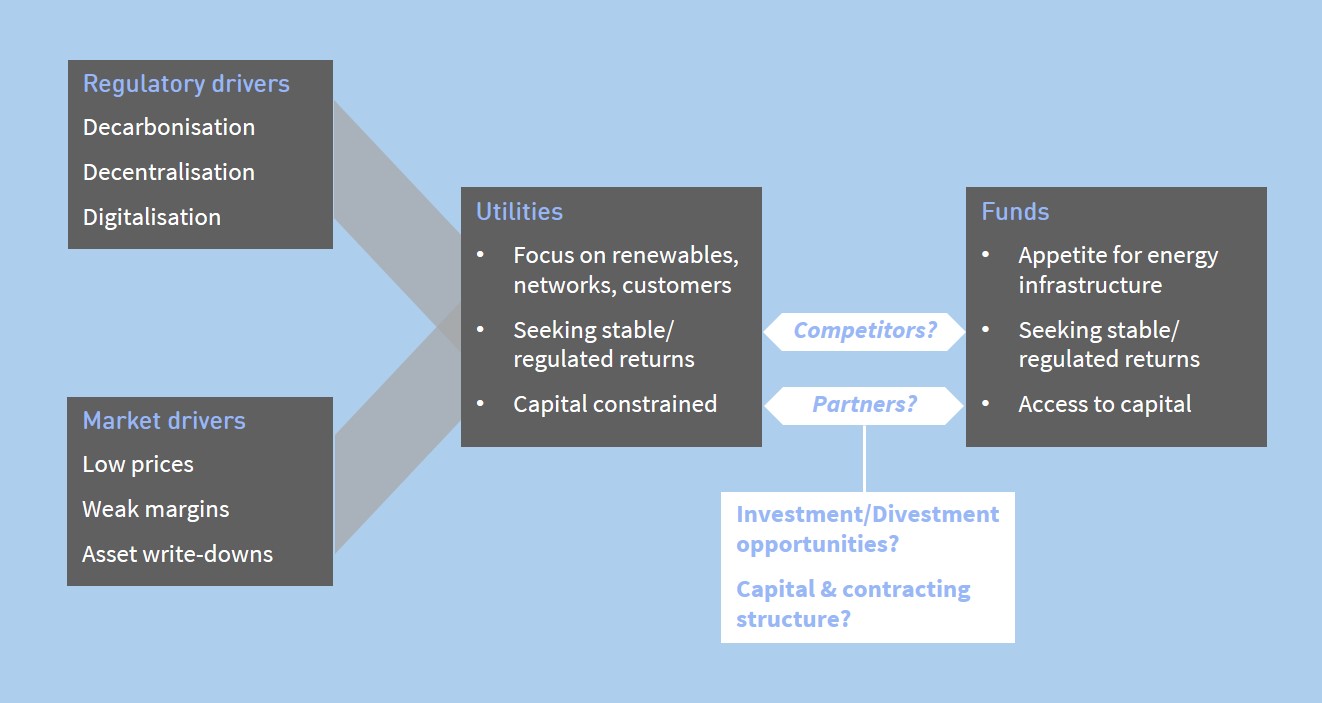

Owners of gas and power assets in Europe are increasingly contracting 3rd parties to provide market access services. This is a function of changing asset ownership structures. Utilities and producers are selling assets to investment funds which lack the in-house trading & commercial capabilities required to hedge and optimise assets.

Last month we wrote an article on the types of market access services being provided by 3rd parties. In today’s article we set out 5 key success factors in structuring and negotiating market access contracts, based on our experience from working with asset owners. We focus on ‘incentivised exposure management’ contracts, the most common and most complex deals to get right.

As covered in our previous article, incentivised exposure management contracts involve the transfer of asset exposures from owner to 3rd party provider, along with incentives to monetise asset value within a defined set of constraints. If a contract is structured well, it allows the asset owner to retain a degree of control over managing asset risk/return. But it also allows for the 3rd party provider to add value through its trading expertise.

In order to illustrate the practical challenges and pitfalls for each of the 5 success factors, we use a case study. This involves a CCGT owner with no in-house trading capability but that wants to be actively involved in determining the forward hedging profile of the asset. This means negotiating a services contract with a 3rd party trading desk that covers market access, plant nomination & dispatch and hedging & optimisation over the prompt horizon (e.g. from the day-ahead stage to delivery).

Table 1 summarises the 5 success factors that we explore in more detail below. These are not in any specific order of priority.

| Success factor |

Summary description |

Pitfalls |

| 1. Governance |

Defining and enforcing guidelines for the management of asset value and risk. |

Asset risk profile not aligned to owner risk appetite. Excessive rigidity constraining trader value creation. |

| 2. Fee structure |

Fair capture of a fixed fee covering overheads and variable fees covering trade execution costs. |

Excess charging for incremental overheads. Excess variable fees incurred due to ‘volume churn’. |

| 3. Incentivisation |

Defining a clean mechanism and value baseline from which trading desk ‘value added’ can be rewarded. |

Alignment of party interests across value, risk & asset performance. Transparency & oversight where this isn’t possible. |

| 4. Exposure transfer |

Clean definition of which party has responsibility for managing asset exposures at any point in time. |

Prompt exposure handover. Information asymmetry in defining value base line. Transfer of ‘monkey value’. |

| 5. Asset representation |

Capturing actual physical asset characteristics in a way that can practically be written in the contract. |

‘Grey areas’ of exposure and value responsibility for each party from over-simplified asset representation. |

Source: Timera Energy

1. Governance:

The ability to define an appropriate risk/return boundary is a primary concern for asset owners, underpinned by the owner’s risk appetite, equity return targets and debt service cashflow requirements. This is achieved via ensuring an appropriate governance structure for a 3rd party agreement.

Defining a robust governance structure is about imposing an appropriate set of guidelines, within which the 3rd party can maximise asset value creation. This is typically implemented in the market access contract via a defined set of controls that provide the owner with appropriate transparency and oversight as to how asset value is being managed by the 3rd party. For example hedging profile guidelines, asset risk metrics and an associated reporting framework.

Challenges & pitfalls

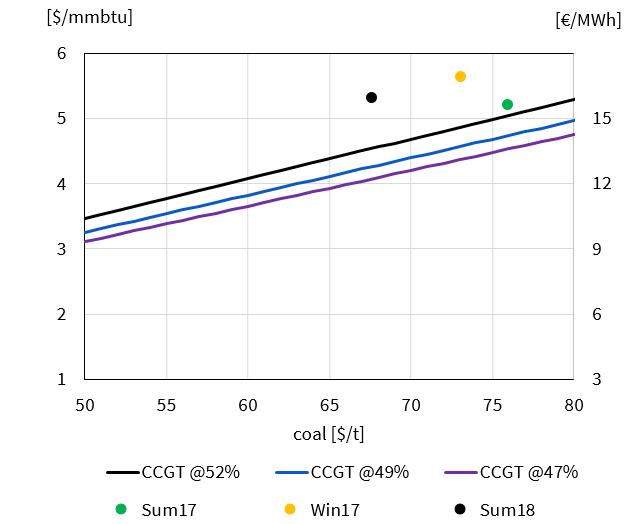

Let’s consider challenges in the context of our CCGT case study. Governance of power plant risk/return is typically based around forward hedging profile guidelines (e.g. min/max levels of hedge cover by time horizon). Associated risk metrics can be used to manage the exposure of unhedged volumes. This structure can be reflected in the market access agreement, along with a means of regular engagement between the 3rd party and owner to determine hedging decisions within the defined guidelines (e.g. via a regular hedging meeting).

A good 3rd party trading desk will create value within the defined CCGT hedging guidelines, e.g. via timing of trading decisions and hedging of spark spread optionality. But providing the trading desk with too much freedom around hedging decisions may encourage excessive risk taking, compromising the owner’s risk appetite. Alternatively, constraints that are too rigid may inhibit the ability of the 3rd party to create value (e.g. specific hedge execution orders vs target hedge ranges).

2. Fee structure

Market access contracts typically consist of a fee structure with fixed and variable components. The fixed fee element aims to reflect the overheads of the 3rd party in providing the contracted services (e.g. trading systems, analytics). The variable fees are intended to reflect the ‘per transaction’ costs of executing trades in the market (e.g. bid/offer spread, credit).

Benchmarking these fixed and variable fee elements is an important part of market access contract due diligence. Fixed fees should reflect the incremental costs of supporting the services provided (reflecting the economies of scale of an established trading desk). Variable costs should be comparable to market bid/offer spreads and credit costs.

Challenges & pitfalls

Ensuring a fair level of fixed and variable fees is becoming easier as competition to provide market access services increases fee transparency. It is easy to focus on the headline fee numbers, but there are other more subtle challenges.

For example the volume of trades undertaken by the 3rd party can have a big impact on asset value accruing to the owner. Higher trading volumes can be associated with greater value creation e.g. from re-optimising forward hedges. But a ‘per transaction’ fee structure can also incentivise the 3rd party to ‘churn’ trades in order to generate variable fee income. This needs to be appropriately captured via incentivisation mechanisms (e.g. netting variable costs) and transparency/guidelines on trading value capture (e.g. ensuring minimum value capture when re-optimising hedges).

3. Incentivisation:

A fundamental challenge of market access agreements is that the interests of the owner and 3rd party provider are not always aligned. The owner is focused on maintaining asset performance and meeting asset risk/return targets, the 3rd party on maximising value generated from the market access agreement (and potentially the value of other assets in its own portfolio). It is important to confront and address this tension when structuring the contract, rather than glossing over it.

Incentivisation structures are a key mechanism that asset owners can use to better align the interests of the contract parties. This is usually focused on defining a clean benchmark for value added by the 3rd party, which is then shared between the two parties. We focus specifically in success factor 4. below on issues in defining this value benchmark.

Challenges & pitfalls

Our CCGT case study can be used to illustrate examples of incentive alignment issues:

- Asset performance: The 3rd party trading desk may increase value capture via more aggressive utilisation of CCGT flexibility. But the owner bears an associated cost in the form of higher outage rates and maintenance charges.

- Risk/return profile: Downside risk for the 3rd party is typically limited by a fixed contract fee, whereas upside from value incentivisation is often uncapped (e.g. via profit sharing). This typically means the 3rd party is incentivised to take greater risk than the owner who bears the true risk/return profile of the underlying asset.

- Value incentivisation: The ability of the 3rd party to add value via trading, hedging and optimisation decisions differs over different time horizons. This can be reflected via a ‘tiered’ incentivisation structure that e.g. reflects a greater potential for the 3rd party to add value in the within-day period close to delivery. But a tiered incentivisation structure can cause further issues if it allows the 3rd party to push asset value into time buckets where it receives a higher profit share.

It is also important to consider how incentivisation mechanisms may change with market conditions (e.g. an increasing portion of plant value being achieved in the within-day market). Careful structuring of market access contracts can either better align party incentives, or ensure appropriate transparency and oversight where this is not possible.

4. Exposure transfer & valuation

Market access contracts by nature mean that two parties have responsibility for the management of asset value. This creates a structural challenge: there must be a clean definition as to who has responsibility for asset exposures at any point in time. The contract should set this out in black and white. It is not an area that benefits from grey.

This challenge typically focuses on the handover of asset exposures from the plant owner to the trading desk in the prompt horizon ahead of delivery. The handover of an owner mandated forward hedging profile can be achieved relatively easily e.g. using traded contract buckets. But the owner typically hands over asset exposures in their entirety close to delivery to allow the 3rd party to fully optimise flexibility in the traded markets (e.g. at the day-ahead stage).

A clean mechanism for transfer of asset exposures between the parties also typically underpins the contract incentivisation structure. This is because the transferred exposures are ‘marked to market’ at the point of handover to form a value baseline against which 3rd party ‘value added’ performance is measured. This baseline is sometimes referred to as ‘monkey value’, the value a monkey or robot could generate before any trader value added.

Challenges & pitfalls

Two key areas often undermine the exposure transfer structure in market access contracts. Failure to ensure:

- Transfer and valuation of exposures against clean executable market price benchmarks

- Fair representation and valuation of asset flexibility (or extrinsic value).

With a CCGT this means choosing a point in time ahead of delivery (e.g. at the day-ahead stage) when there is a clean price benchmark against which plant optionality can be optimised and transferred. From this point the 3rd party then assumes full control for creating further value in the within-day, balancing and ancillary services markets.

It is also common for the incentivisation link to result in ‘value bleed’ from the asset owner to the 3rd party, due to the exposures being undervalued at point of transfer between parties. The CCGT owner is confronted here by an important information asymmetry. The 3rd party will typically have a strong commercial and analytical capability to allow it to fully value plant flexibility. Whereas the owner may fall back on a simpler valuation mechanism to determine the value baseline for incentivisation in the contract. Confronting this issue to define a fair value benchmark is key to avoiding structural value bleed via giving away ‘monkey value’.

5. Asset representation

The final success factor we cover is how to represent a complex physical asset in a contract. This means striking the right balance between accuracy and practicality.

Getting asset representation right is important because it forms the foundation from which each of the two parties responsibilities are defined. It also underpins the management and transfer of asset exposures and the incentivisation of 3rd party performance.

In the interests of contract simplicity it is tempting to represent the asset in the market access contract at a simplified level. But this can result in ‘grey areas’ of contract interpretation which typically favour the 3rd party by opening opportunities to optimise value in its favour.

Challenges & pitfalls

The CCGT case study provides examples of some factors to consider:

- Considering the plant at an aggregate level rather than breaking it down into individual units (or even sub-units e.g. to cover excess output from duct-firing)

- Fully representing market granularity as opposed to aggregating exposures into non-traded buckets

- Adequate capture of plant physical characteristics (e.g. ramp rates, start cost structure)

- Robust treatment of outage risk, defining owner responsibility for asset performance but 3rd party responsibility for unwind of hedges (within realistic liquidity costs)

A key principle that helps with the clean structuring of market access contracts is ensuring that asset representation allows exposures to be allocated and priced by the party best placed to manage them This can be assisted by a review clause in the contract, to recalibrate the asset representation periodically.

Getting contracts right

Traders are experts at optimising within a given set of constraints to create value. This expertise can be harnessed via a well-structured market access contract to significantly increase an asset owner’s returns. In areas where trading expertise can really add value it can often make sense to strongly incentivise this (e.g. 25-50% profit share).

But it is a double edged sword. Trading desks will also optimise any loopholes in market access contracts, usually to the detriment of the asset owner who is at a clear disadvantage in identifying issues. In many cases loopholes are the result of weaknesses in the way the contract is structured before it is signed. In other words the loopholes are baked into the contractual relationship, often with the explicit knowledge and intent of the trading desk.

In some areas there is nothing an owner can do. There is a balance between structural complexity and practicality. But recognising potential loopholes and structuring incentivisation mechanisms accordingly is an important way of preventing value bleed.

As market access contracts continue to evolve, standardisation of terms should work in an asset owner’s favour. But that may take several years. In the meantime considering the 5 success factors above should help with a number of potential challenges and pitfalls.

Article written by David Stokes, Olly Spinks and Nick Perry