Tightening emissions standards are supporting structural growth in the uptake of LNG as a shipping fuel. Europe has led this transition, dominating the fleet of existing vessels and associated infrastructure. But growth is now accelerating globally.

LNG bunkering has created considerable excitement as a new source of demand in the LNG market. Today we look at the drivers and potential scale of LNG demand growth from shipping.

Emissions regulations driving change

In 2016 the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) announced requirements for significant reductions of marine fuel sulphur by 2020. Under the new provisions, marine fuel used in ships will have to have a sulphur content of no more than 0.5% versus the current limit of 3.5%. Emissions standards have already been tightened to a cap of 0.1% for designated Emission Control Areas (ECA’s) for coastlines in the US and Northern Europe.

The IMO 2020 regulations will require ship owners to decide whether to:

- continue using high sulphur fuel oil and add scrubbers/exhaust gas cleaning systems or

- switch to low sulphur fuel options i.e. distillates or LNG.

Tighter emissions standards are acting as a tailwind for LNG-fuelled vessels.

Growing fleet & order books

There is an existing global LNG-fuelled fleet of around 120 vessels. More than 60% of these are European based. LNG consumption of the current fleet is around 0.25 mtpa.

The fleet has been growing recently at a rate of about 20% a year, with a current global order book of a similar size to the existing fleet.

While this headline growth rate is impressive, understanding different vessel classification segments is important for estimating implications for LNG demand growth. This is the primary reason for uncertainty in forecasts of future bunker fuel LNG consumption.

Passenger ships account for around 35% of existing and ordered vessels. Demand here is driven by leading cruise ship operators placing orders to help avoid emissions constraints in city ports.

But the strongest recent growth in vessel demand has been for larger LNG-fuelled tankers and bulk carriers. In addition to an in-service fleet of 19 vessels, 10 chemical/product tankers have been ordered. Four Aframax ice class oil tankers have been ordered by Socomflot which will be taken on charter by Shell.

The LNG-fuelled marine industry focus is shifting from Norway and the Baltic region northern Europe and North American trade. Four of the LNG fuelled vessels in operation already operate globally and 22 newbuilds are also destined for global trade.

Oil and gas offshore industry service vessels rank second in terms of LNG uptake. However, this is unlikely to be a major source of significant future growth.

Higher growth is expected in the tanker, car/passenger, cruise and container segments. Container ships are well suited for LNG fuel, with fixed routes and a high fuel consumption to earn back the additional investment.

In late 2017 Total agreed to supply French shipping firm CMA CGM with around 300,000 t/year of LNG bunker fuel for 10 years from 2020 – the largest such contract to date. CMA CGM has ordered nine 22,000 twenty-foot equivalent unit (TEU) container ships with LNG fuelled engines. The French government is planning to support development of LNG bunkering infrastructure at the country’s ports.

LNG bunkering infrastructure

LNG bunkering infrastructure is currently concentrated in areas affected by the existing tighter ECA emissions standards and with access to LNG from regas or liquefaction related storage tanks and port facilities. These include:

- North west Europe (for example, in the ports of Rotterdam, Stockholm and Zeebrugge)

- The US Gulf and East coast (including the ports of Jacksonville and Fourchon)

These make up the bunkering nodes around which a global LNG-fuelled shipping industry will be developed.

Key Asian ports serving deep-sea shipping routes are in the process of establishing LNG bunkering facilities and looking to co-ordinate activities with their European and North American counterparts. This is most evident in the infrastructure being developed by Singapore and in ports in eastern China, for example Ningbo-Zhoushan, the world’s biggest cargo port.

Chart 1: Global infrastructure for LNG bunkering

Source: DNV.GL

Current EU policy requires at least one LNG bunkering port in each member state. About 10% of European coastal and inland ports will be included, a total of 139 ports. Coastal port LNG infrastructure will be completed by 2020 and for inland ports by 2025.

There are several ports under development in North America, mostly in the south east, the Gulf of Mexico and around the Great Lakes, but also for ferry and deep-sea operations in the Pacific Northwest.

China is extending LNG bunkering infrastructure from inland waterways to coastal areas and is expected to be able to service the LNG demand of all vessel types. South Korea offers LNG bunkering in the port of Incheon and is considering a second facility in Busan. Elsewhere in Asia, in addition to Singapore, Japan and Australia are also working to develop LNG bunkering facilities.

Potential impact on global LNG demand

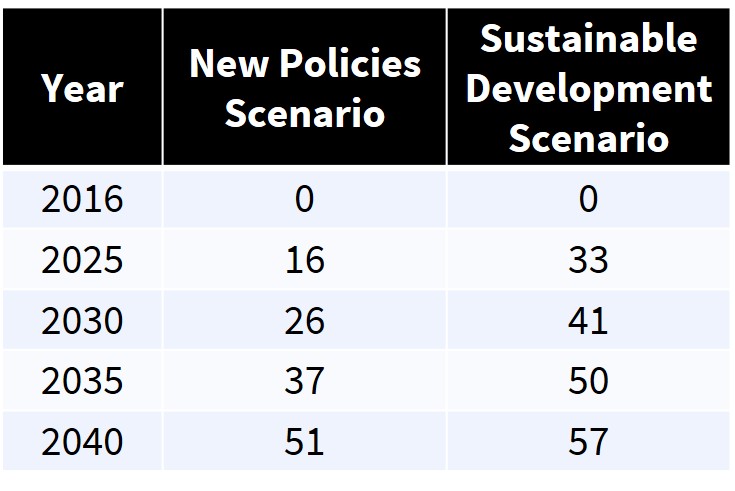

The IEA, in their 2017 World Energy Outlook, see the use of LNG replacing heavy-fuel oil as a bunker fuel providing around a 25% reduction in CO2 emissions. Notwithstanding the challenges in forecasting LNG bunker fuel outlined above, the IEA make the following projections for their ‘New Policies Scenario’ and a ‘Sustainable Development Scenario’. In the latter it is assumed that the IMO limits on sulphur are further tightened – hence the increased LNG consumption in bunkering.

Chart 2: IEA LNG marine fuel demand forecast (bcma)

Source: IEA World Outlook 2017

To put these LNG bunkering demand numbers in context, they are equivalent to the projected demand growth of one of the larger emerging Asian buyers e.g. Thailand or Pakistan.

As such LNG bunkering is an interesting demand growth trend to keep an eye on. But it is unlikely to have a transformational impact on global LNG market demand.

| Timera is recruiting power analysts We are looking for a Senior Power Analyst and a Power Analyst with strong industry experience. Very competitive & flexible packages. Further details at Working with Timera. |

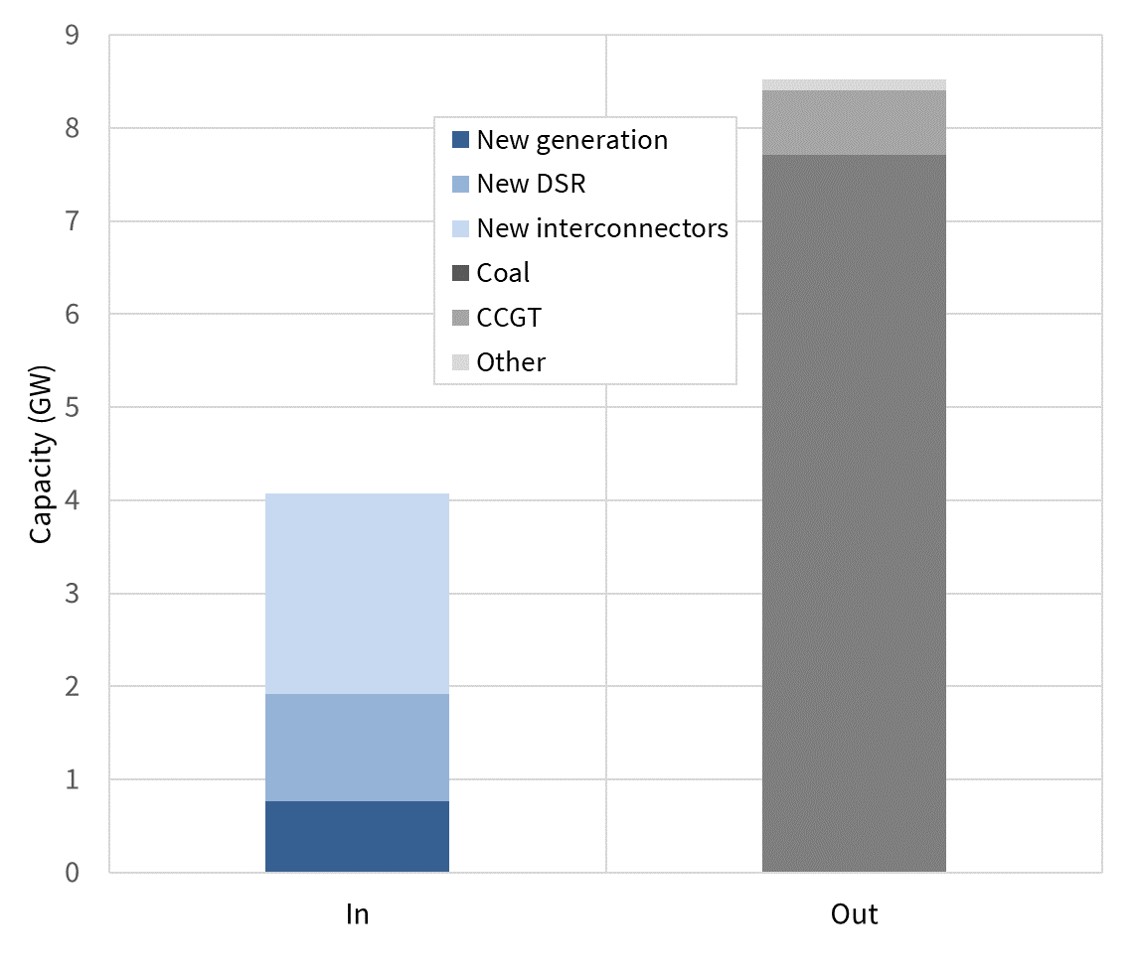

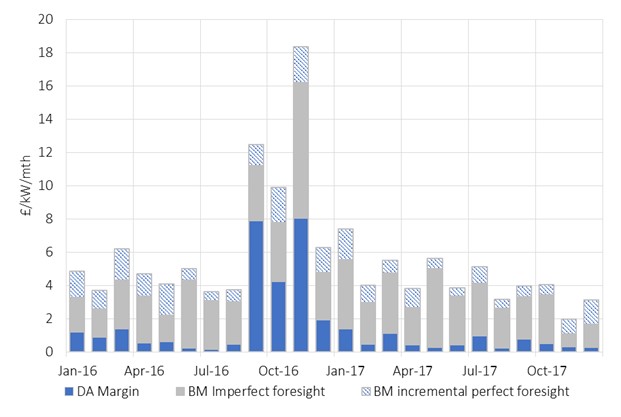

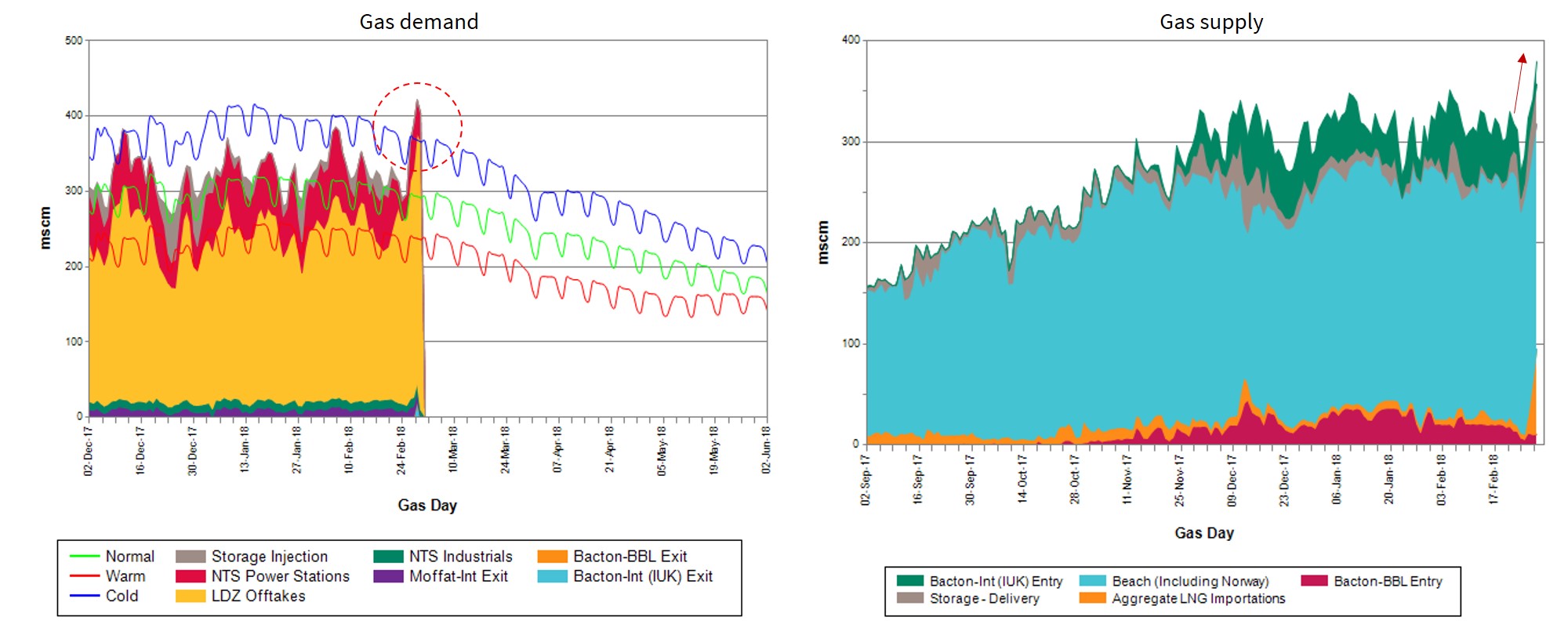

Source: National Grid

Source: National Grid