Belgium’s nuclear driven capacity crunch

Nuclear power is not popular in Belgium. Belgium’s nukes are even more unpopular with Germany and the Netherlands, given their locations near these borders and chequered safety record.

Belgium’s reactors are ageing and have suffered several major safety and maintenance issues over the last 5 years. In response to these factors, the Belgium government agreed an energy plan on 30th Mar 2018 that confirms the phase out of nuclear power by 2025.

In practice this means Belgium needs to replace half of its generation output in the next 7 years. This is clearly a major challenge. And Belgium’s newly approved strategic reserve mechanism is unlikely to incentivise adequate replacement capacity.

This means that Belgium is currently heading towards a mid 2020’s capacity crunch. It is doing so as key neighbouring markets (France, Netherlands & Germany) also face tightening capacity balances.

The hole created by nuclear closure

Belgium has 7 nuclear units:

- 4 units at the Doel site (on the Dutch border north of Antwerp)

- 3 units at Tihange (in Eastern Belgium, about 40km from the Dutch & German borders)

The Mar 30 plan schedules closures of 1GW in 2022, 1GW in 2023 and the remaining 3.9GW in 2025.

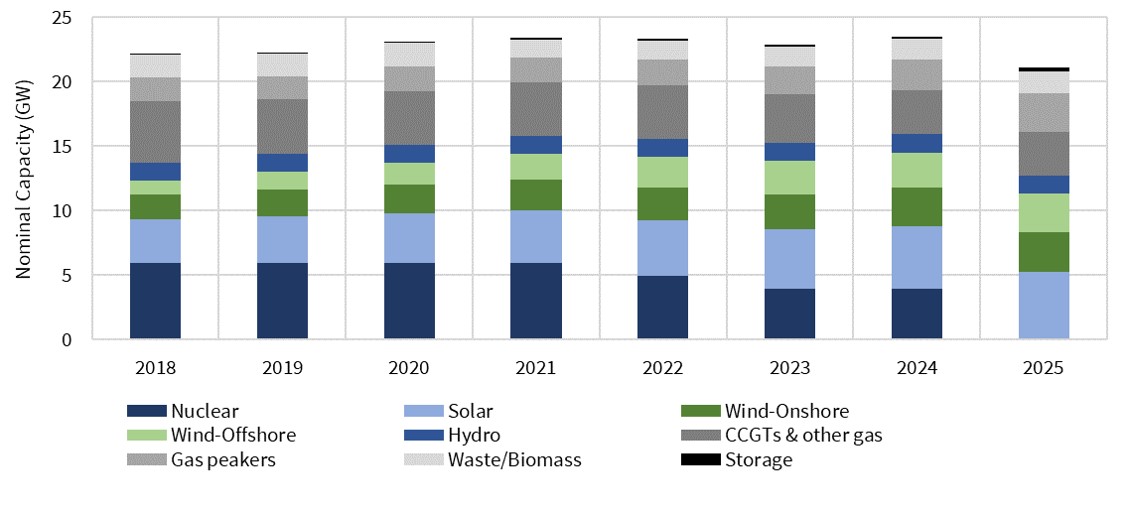

These units currently make up 27% of Belgian capacity (5.9GW of a total 22GW), but they account for approximately 50% of Belgium’s generation output.

The easiest solution for replacing lost generation output would be to import more power. But Belgium’s regulatory authorities and system operator have clearly stated they do not want to increase import dependency for security of supply reasons.

So it is clear Belgium needs replacement capacity. What is not clear is where that capacity will come from.

Can renewables plug the gap?

Belgium currently has approximately 3GW of wind and 3.5GW of solar capacity. Based on current policy support mechanisms, technology cost reduction curves and recent build rates, it is our view that Belgium can develop an additional:

- ~3GW of wind by 2025 (dominated by offshore)

- ~2GW solar by 2025.

In addition, we assume development of ~1GW of gas peaker capacity (dominated by distribution connected reciprocating engines) and ~0.5GW of battery storage by 2025.

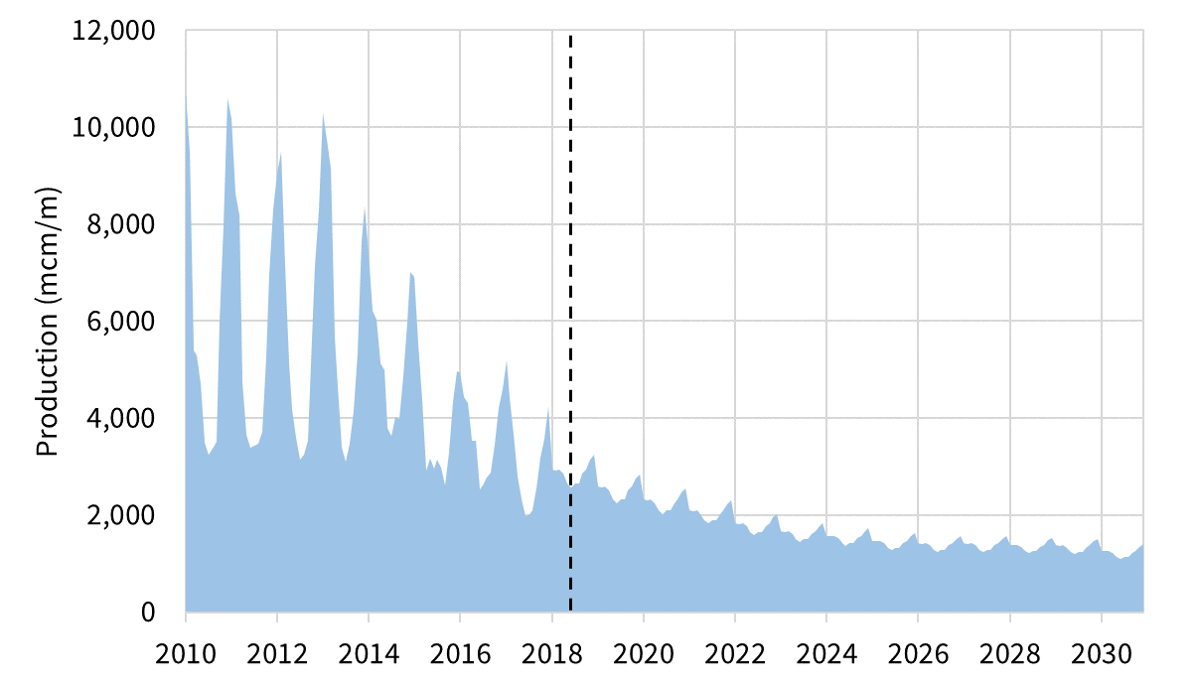

This results in the nominal capacity mix scenario shown in Chart 1 (which also accounts for end of life retirements of some older thermal capacity). This scenario assumes no new large-scale gas build, consistent with a current lack of policy & market price signal support.

Chart 1: Scenario for evolution of Belgium capacity mix – assuming no large-scale gas build

Chart 1 however does not reflect the true security of supply problem Belgium faces replacing nuclear with wind and solar capacity. Wind and solar output needs to be derated to reflect the equivalent firm capacity that can be relied on given load factor fluctuations.

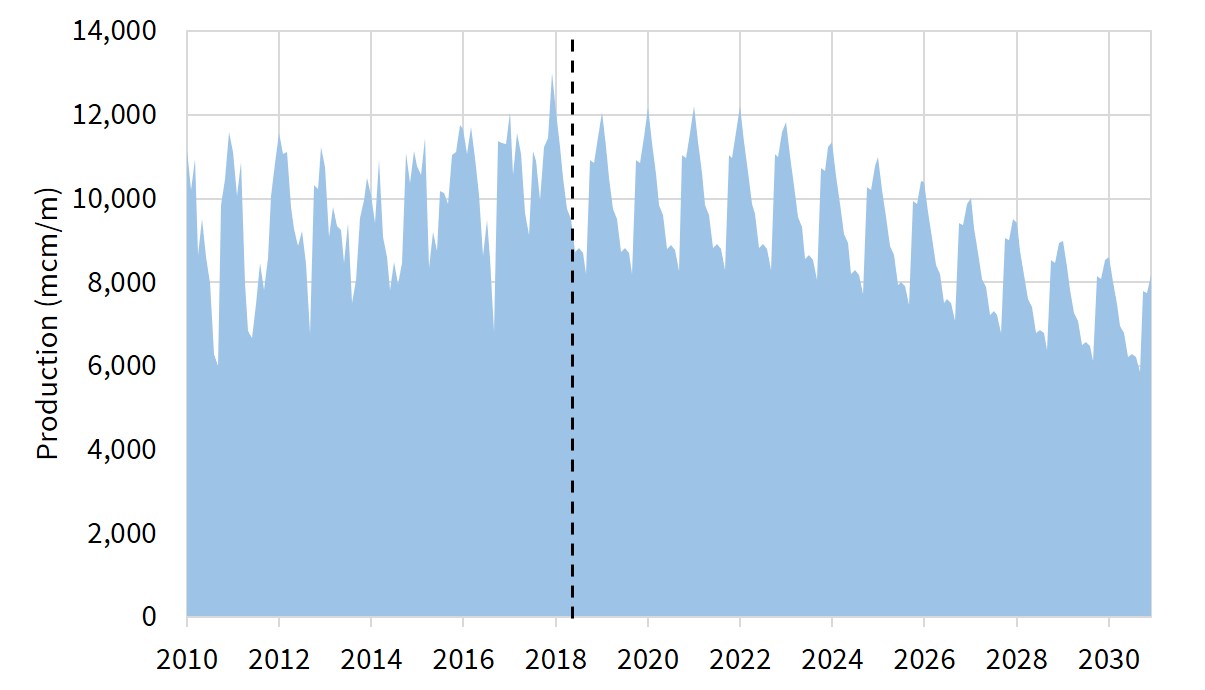

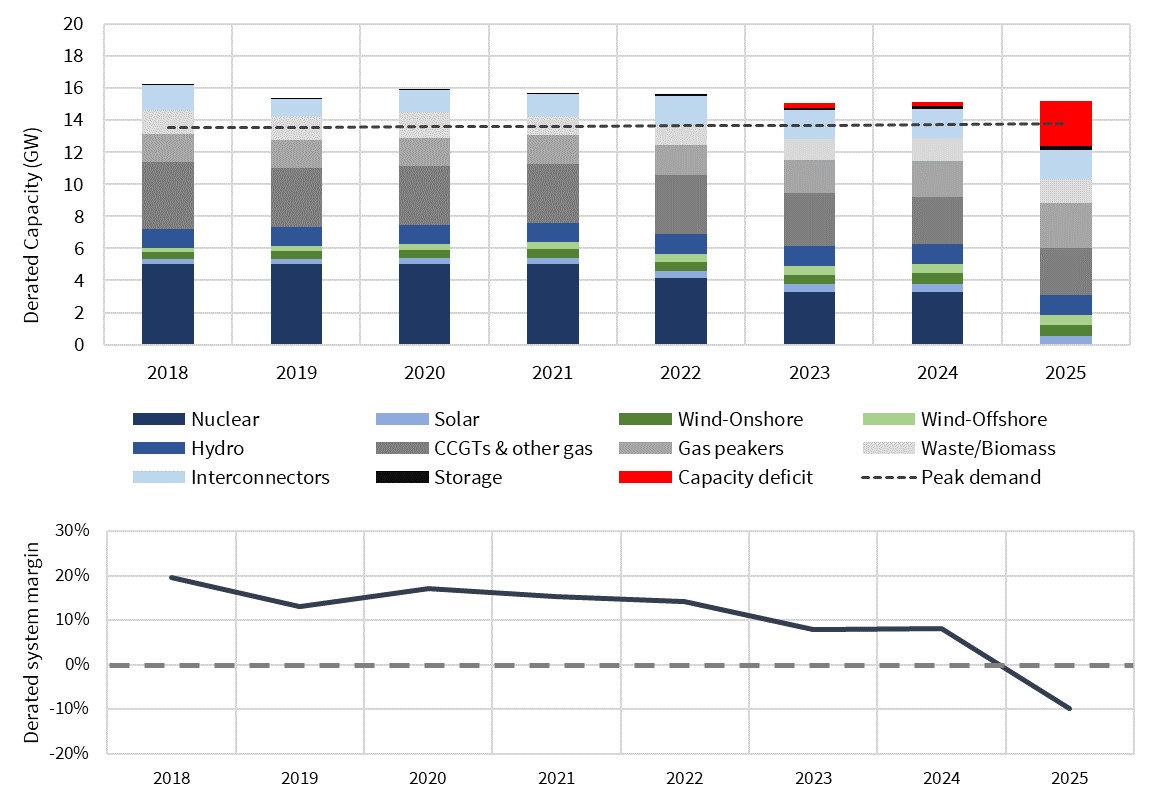

Once 3GW of wind and 2GW of solar build is derated, it yields only about 1GW of equivalent firm capacity. This leaves an almost 3GW capacity deficit in the Belgian market by 2025, with the derated system reserve margin plunging into negative territory as illustrated in Chart 2.

Chart 2: De-rated Belgium capacity mix

What if our renewable build assumptions in the scenario above are too conservative? Even with much more aggressive policy support, it is difficult for Belgium to develop more than 1.5GW of equivalent firm renewable capacity by 2025. This would still leave a ~2.5GW capacity deficit to be filled.

Where is the price signal for flexible capacity?

A 3GW capacity deficit is not a massive technical challenge. Two large CCGT plants would plug the gap. But this solution may be inconsistent with the backdrop of decarbonisation.

Firstly from a policy standpoint, Belgium is likely to be wary of large scale new gas build from an emissions reduction perspective.

Secondly from an economic standpoint, it will be hard to find investment capital willing to commit to new CCGT projects (with 20 year economic lives) commissioning mid next decade. Investors face unpalatable margin risk relying on wholesale price signals alone, as well as the broader risk of stranded assets (as Dutch coal plant developers are painfully discovering).

If Belgium is going to plug its capacity gap with new gas plants, a clear price signal will be needed to secure investment. Belgium has no plans to implement a capacity market (as have the UK, France and Italy). Instead it gained EU state aid approval in Q1 2018 for a strategic reserve mechanism.

Belgium’s strategic reserve initially covers 5 winters from 2017-18. Reserve capacity sits outside the energy market and is called on only in periods of security of supply emergency. As such it can be used to prevent uneconomic older plants from closing. But it is unlikely to send a clear capacity price signal to support new build of flexible capacity.

CHPs may play a role in plugging the 3GW capacity deficit. This could either be smaller distribution connected CHPs (easier but lower volume) or large-scale grid connected assets (more challenging). But adequate policy support mechanisms to deliver significant volumes of CHP are not yet in place.

Where does this lead?

If nuclear plants are closed by 2025, it is difficult to see how Belgium can maintain (i) security of supply and (ii) similar levels of wholesale prices without 2-4GW of new gas-fired capacity. But it is not clear how this capacity will get built in the absence of new policy measures.

The capacity gap may be reduced somewhat by a combination of aggressive role out of renewables & storage as well as tolerance for higher import dependency. But these measures are unlikely to be enough.

There is recent evidence from 2014-15 of the impact of a rapid reduction in Belgium nuclear capacity. Prices separate from neighbouring markets and volatility jumps, with a focus in winters, peaks and periods of lower renewable output. Higher Belgium prices can also drag up French and Dutch prices as imports increase.

Belgian policy makers may be forced to confront the reality that the current path they are proceeding down is not going to work. But they are in good company.

Their biggest neighbour Germany is facing a similar, but much larger problem as it tries to close nuclear, coal and lignite capacity in parallel. We’ll come back soon to address the German problem and its implications for other European power markets.

| Timera is recruiting power analysts We are looking for a Senior Power Analyst and a Power Analyst with strong industry experience. Very competitive & flexible packages. Further details at Working with Timera. |