Battery storage broke through the investment viability barrier in the UK’s 2016 capacity auctions.

200MW of batteries were successful in the 2016 Enhanced Frequency Response (EFR) auction. Battery bids were so low that they caused the price for 4 year frequency response contracts to crash below the prevailing shorter term price for Firm Frequency Response (FFR), despite EFR being a faster response service.

A further 500MW of batteries gained capacity agreements in the 2016 T-4 Capacity Auction. This wasn’t just a big story in Europe, but a huge boost to the global deployment of storage as an economic source of flexible capacity.

But UK battery developers have been forced to regroup after this initial surge. The viability of the business model that underpinned 2016 success has been eroded by three factors:

- FFR: The sharp reduction in Firm Frequency Response (FFR) market prices as battery penetration has risen.

- EB: Policy intervention to reduce the level of embedded benefits (EB) for distribution connected assets.

- CM: Steep reductions in the de-rating factors applied to short duration batteries in the UK Capacity Market (CM).

As a result, battery developers and investors are now refocusing on generating margin from price arbitrage in the wholesale market and Balancing Mechanism (BM).

In this week’s article we explore the different business models that battery developers are adopting and look at the economics of storage investment. In an article to follow we consider the practical challenges of value capture from wholesale price arbitrage.

Battery business models

The success of batteries in 2016 was underpinned by frequency response and capacity market returns. Substantial reductions in these sources of income have forced developers to evolve their business models.

The current range of battery projects being developed vary widely in both scale and business model. However, business models can be broadly grouped into 4 categories:

- Behind the meter

- Distribution connected

- Transmission connected

- Hybrid

We summarise each in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Summary of four battery business models

| Business Model | Description |

|---|---|

| Behind the meter | Batteries are being deployed behind the meter to optimise onsite load, reduce supplier charges and provide DSR services. Behind the meter deployment presents specific opportunities and challenges. Each site is typically relatively small in scale. Business models typically focus on avoiding supplier levies which requires a thorough understanding of customers load profiles and supply contract terms.

Batteries also often interact with onsite load to create value. The economics of behind the meter energy are ‘use case’ specific and hence business models tend to focus more on client engagement, onboarding and technology allowing control over multiple sites efficiently and effectively. |

| Distribution connected | The advantages of distribution connection of batteries are driven by embedded benefits revenues (e.g. triads, GDUoS). Business models are therefor more closely aligned to those for gas engines, where opportunities for embedded benefits are driven by location and site/connection specific factors. As the opportunities for lower voltage connections are becoming increasingly competitive and as policy changes have eroded embedded benefits, the gap between transmission and distribution connected battery economics has narrowed. |

| Transmission connected | The advantages of transmission connection lie principally in connection costs and scale economics. Grid connection precludes access to embedded benefits. But there can be cost advantages with grid connection as well as the opportunity to generate TNUoS related revenues from location in the right locations. Scale also typically brings down project costs, particularly in relation to supporting technology and infrastructure. |

| Hybrid | There are also several hybrid approaches being adopted where batteries are deployed in conjunction with other assets e.g. Limejump’s recent Virtual Power Plant. These include siting batteries alongside wind and solar projects, as well as integrating with gas engines and EV charging stations. The benefits of such hybridisation lie in shared infrastructure (e.g. grid connections) and different risk profiles which may tip a borderline investment case into the green. |

Battery economics & margin stacking

Beyond these four basic business models, lies the question of how a battery investment can capture adequate value across different margin buckets. Solving this margin stacking problem underpins a viable investment case (as it does for gas reciprocating engines).

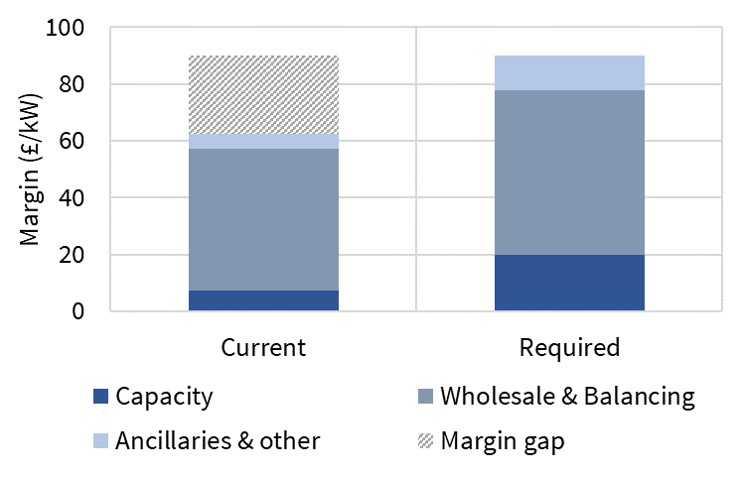

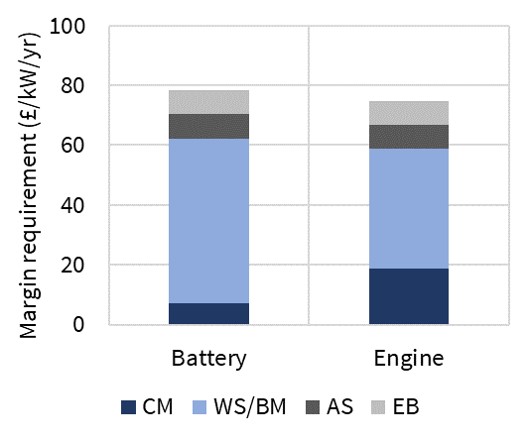

But the original margin stacking model adopted in 2016 has been transformed by the reductions in FFR, EB & CM margins (described above).

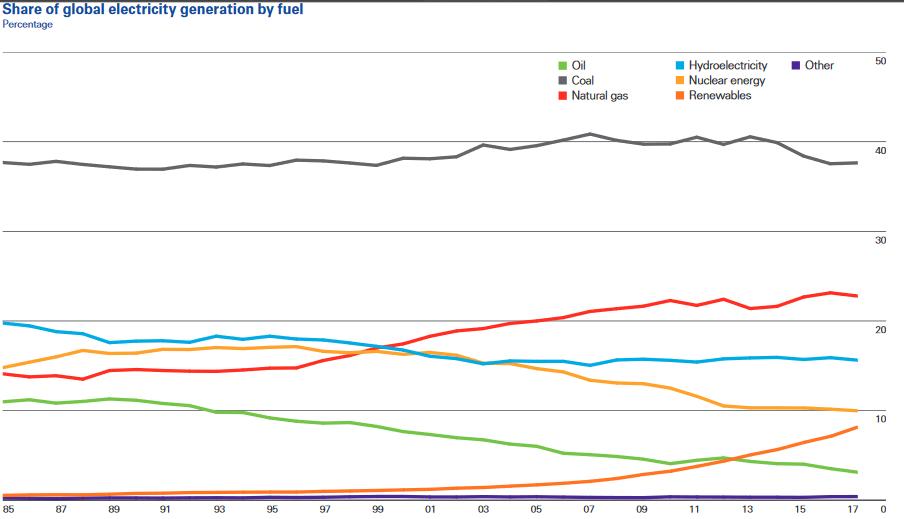

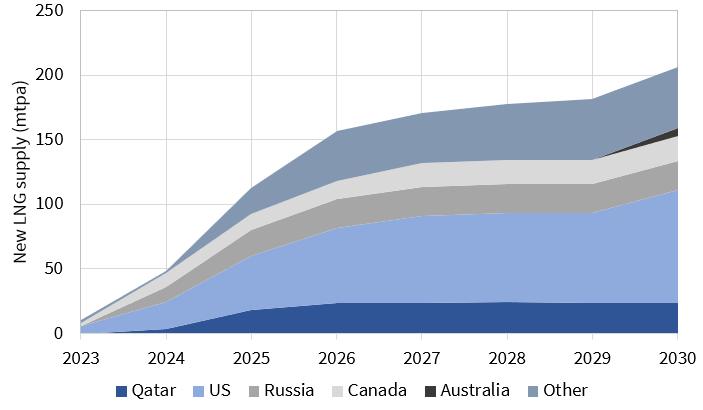

As a result, battery developers are transitioning to merchant business models that focus on capture of market price fluctuations in the prompt wholesale market and BM. Chart 1 shows a breakdown of margin required to support a merchant battery project. A merchant gas engine breakdown is shown for comparison.

Chart 1: Battery technology & economics

Source: Timera Energy. CM = Capacity Market. WS/BM = Wholesale/BM. AS = Ancillary Services. EB = Embedded Benefits.

Chart 1 is based on a 1 hour duration lithium-ion battery project. At the moment, the cost advantages of batteries of around 1 hour duration outweigh the revenue benefits of higher volume load shifting from longer duration batteries (e.g. 4-6 hours). This could change in the 2020s depending on the relative pace of decline in storage technology cost curves. But for now, short duration L-ion batteries are the big player in town.

The ‘all in’ costs for short duration battery projects are in the order of 400 £/kWh (i.e. 400 £/kW for a 1 hour duration battery). That means an average annual real return of about 80 £/kW/yr is required (assuming a mid-life refresh of battery units to boost performance).

Capacity market margins for shorter duration batteries took a big hit from last year’s policy change to reduce derating factors. This means that battery investment returns are now even more focused on wholesale & BM value capture than for gas engines (typically 50+ £/kW/yr of margin required).

This brings us to the two biggest challenges that battery developers are currently facing:

- Quantifying a realistic level of wholesale market & BM value capture

- Presenting a robust view of asset risk/return profile to investors to raise capital

We come back to explore these value capture considerations in an article to follow shortly.