Foreign investor interest in the Spanish power market has ebbed and flowed since deregulation. Over this period, Spain has benefited from substantial foreign ownership and investment in energy assets. But investment conditions over the last 5 years have been tough.

Spain was one of Europe’s leaders in renewables deployment at the start of this decade. But the previous conservative government slashed policy support in 2013 given cost blow outs, with cuts applied on a retroactive basis. Investor’s backed off accordingly with renewable investment grinding to a halt.

A significant overhang of thermal capacity also emerged across the first half of this decade. This was the result of robust investment in new generation last decade, just in time for the financial crisis to erode power demand.

But there are early signs of a shift in the winds. A new minority government is stepping back behind renewable investment (reinforced by a pickup in PPA deals) and is accelerating coal closure timelines. Generation portfolio owners are also mulling over the sale, mothballing or closure of gas & coal fired assets in what could precipitate a major market shake-up.

Action is likely to be centred around Spain’s 26GW CCGT fleet. In today’s article we look at key value drivers for Spanish CCGTs.

Spanish market 101

A 40,000 foot perspective of the current Spanish supply & demand balance is useful background to understand asset value drivers.

Spanish power demand peaked in 2008 and then declined with economic growth after the financial crisis. Demand has however steadily recovered since 2015, in line with economic growth. Demand peaks in the winter, although summer peak demand levels are approaching the winter peak as air-conditioning load increases. Demand is likely to rise in the 2020s due to a combination of the electrification of transport and space heating/cooling.

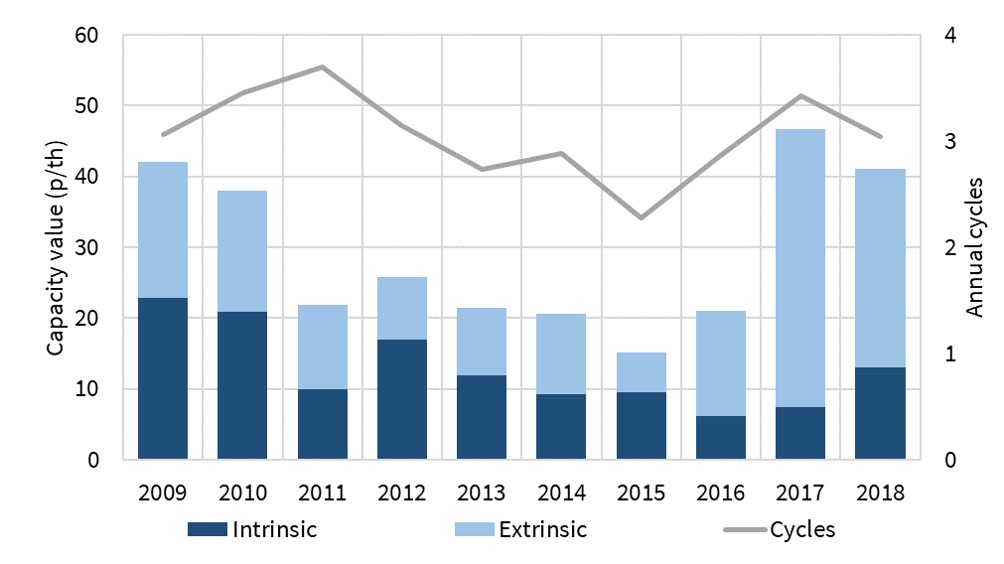

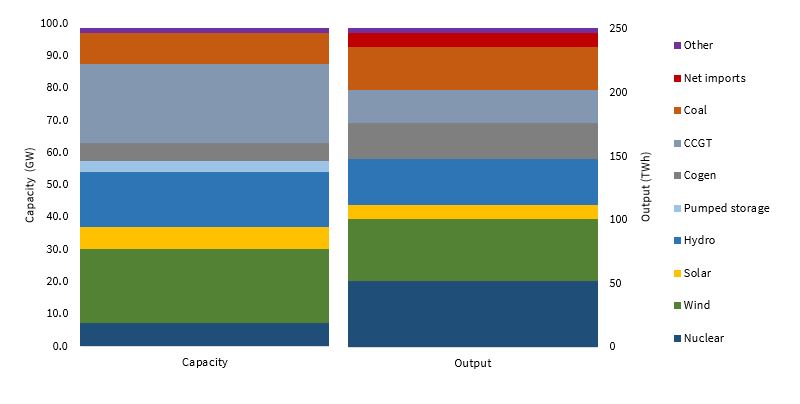

The Spanish capacity and generation output mixes are summarised by technology type in Chart 1.

Chart 1: Spanish generation capacity (GW) & production output (TWh)

Source: Timera Energy, Red Electrica

The bottom half of the Spanish supply stack is dominated by low variable cost capacity. Nuclear and wind account for around 20% of annual generation output each. In addition there is another 5% of solar output (set to expand as investment picks up again) and 3-5% of net imports (cheaper power from France & Portugal). Coal and gas-fired plants then provide the flexibility required to balance the market.

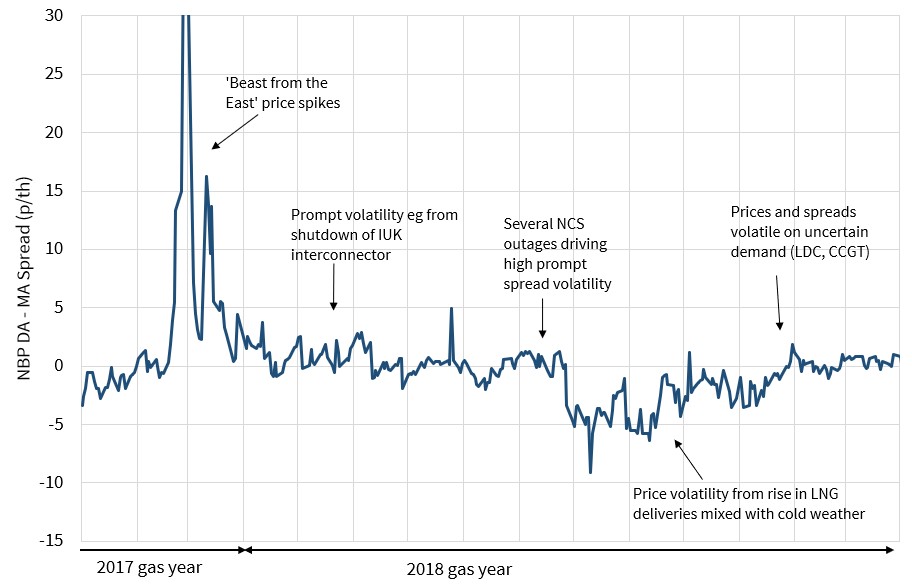

Spain has substantial swings in hydro output dependent on rainfall & storage levels as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Historical hydro output versus system demand

Source: Red Electrica

In a dry year (e.g. 2016), Spanish hydro accounts for around 6% of demand. In a wet year that can rise above 15%. The right hand column gives an indication of the probability of exceeding the level of hydro output in each year (low % if a wet year, high % if a dry year). Swings in hydro output are an important driver of gas and coal plant load factors (which rise in dry years).

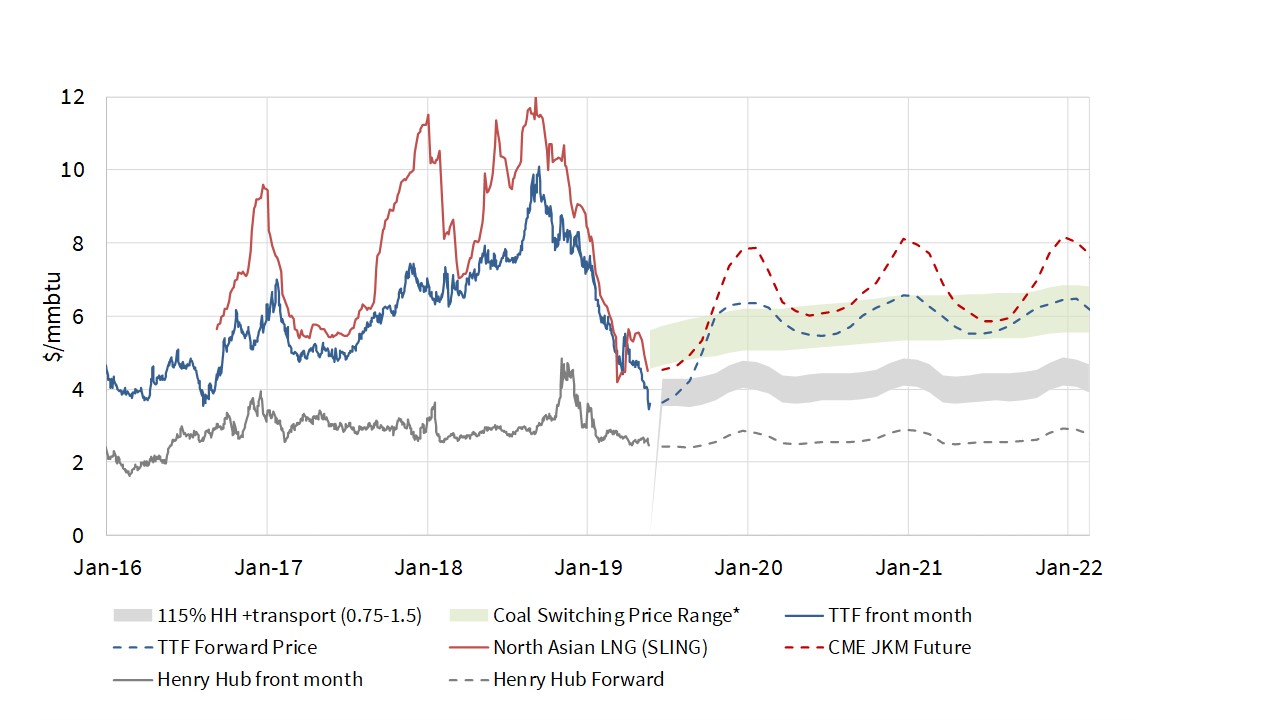

The other important dynamic that impacts thermal asset load factors is relative commodity price levels. The overhang of capacity and falling demand, pushed CCGTs into a peaking flex provision role by the middle of this decade. But CCGT load factors have started to rise again across 2018-19, as falling gas prices and rising carbon costs erode coal plant competitiveness.

CCGTs have also benefited from a Q4 2018 cut to the ‘green cent’ tax on gas consumption, reducing variable costs (by ~4 €/MWh).

These shifts in competitive balance are reinforcing the importance of gas in setting marginal power prices in Spain.

Key issues impacting CCGT value

From a CCGT owner’s perspective, the list of concerns about value evolution can be grouped into 3 buckets.

1.Capacity payments

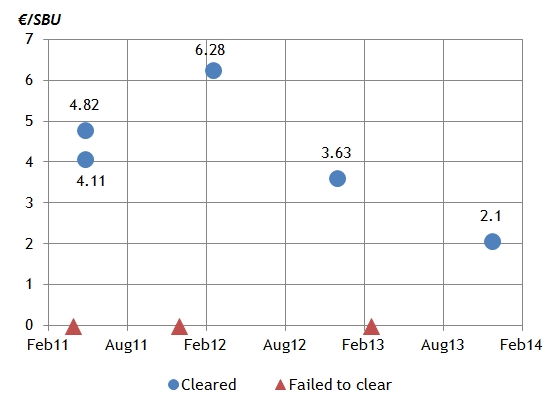

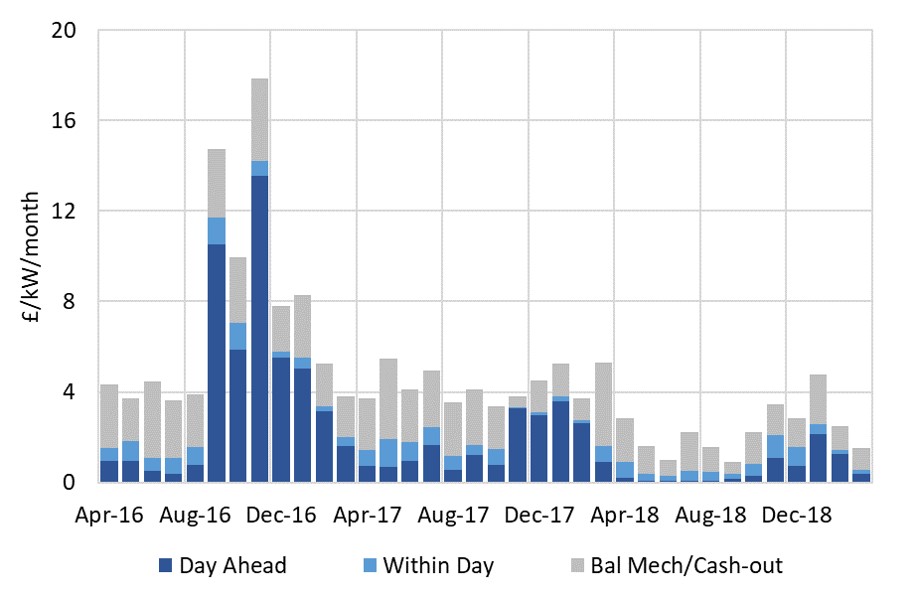

As load factors have declined, CCGTs have been ‘kept alive’ via two forms of capacity payment:

- Availability payment (~5 €/kW)

- Investment subsidy (~10 €/kW)

But this life support is being pulled. The availability payment was suspended last year given government concerns around EU state aid review. Around 70% of Spanish CCGTs will lose the investment subsidy by 2021.

There is a strong lobby voice from CCGT owners against capacity payment removal, with legal challenges underway on subsidy suspension. Some revised form of capacity payment support is likely going forward, but the risk around the timing & level of this is borne by asset owners.

2.Capacity mix evolution

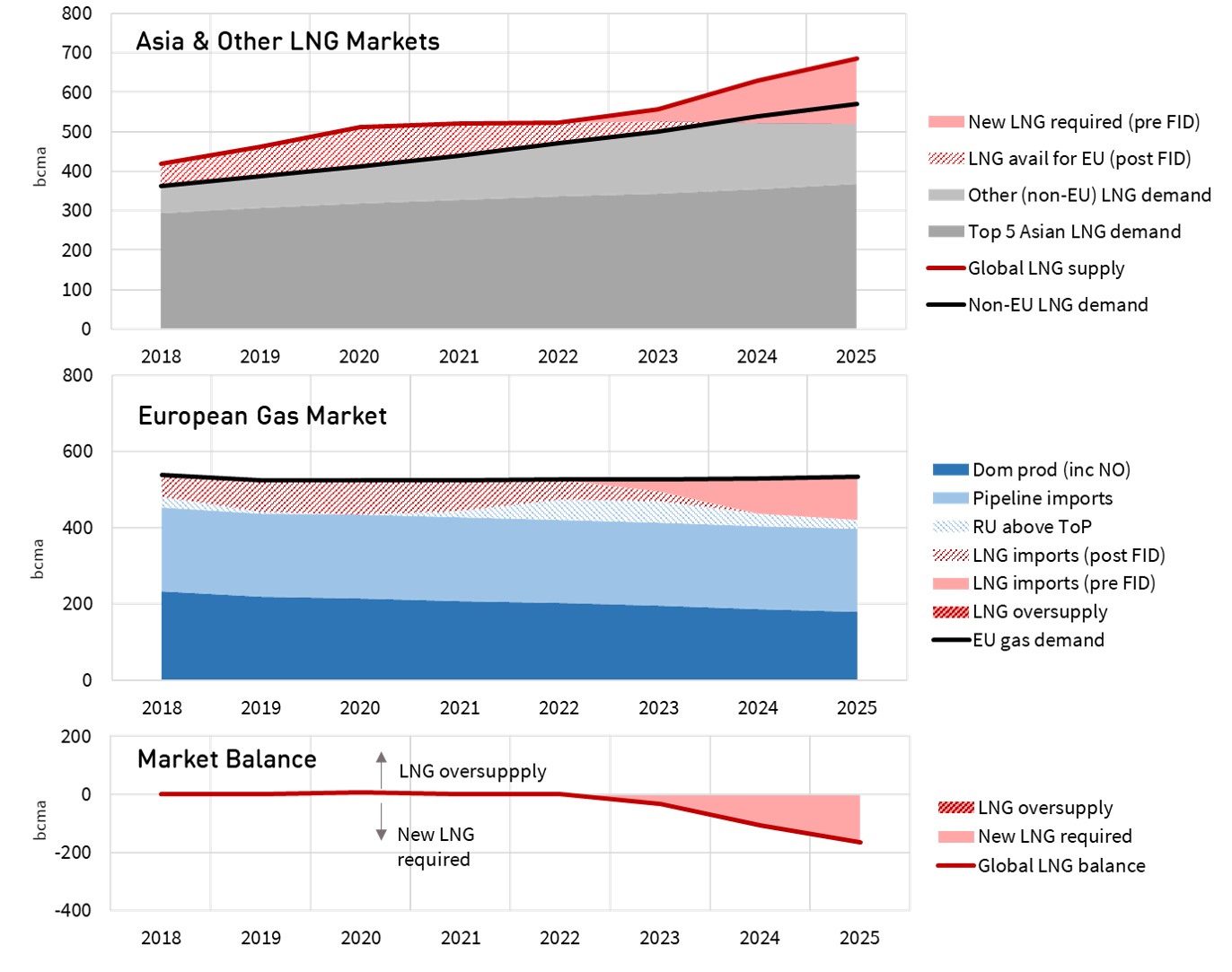

Changes in the Spanish capacity mix will be key to alleviating the current overhang of capacity that is undermining CCGT margins. The ability of the new government to revive renewable investment, will be an important factor across the 2020s. But there are some more immediate factors in play.

Half of the Spanish coal fleet (5GW) will close by Jun 2020 driven by EU emissions legislation, removal of coal subsidies and the closure of domestic coal mines. The new government is now aiming to close the remaining 5GW of coal capacity by 2025. Adverse market conditions (low gas & high CO2 prices) could accelerate this.

Plant owners have also faced regulatory constraints around closing or mothballing CCGTs, exacerbating excess system capacity. But these are likely to be eased as capacity payments are removed. This should see older and less flexible CCGTs coming offline e.g. Naturgy (the rebranded Gas Natural Fenosa) is currently seeking approval to mothball 2GW.

Significant closures of Spanish nuclear plants are likely to start in the second half of next decade.

3.Load factors & wholesale margins

The average load factor across the Spanish CCGT fleet is currently around 20%. Behind the average utilisation of individual assets can vary significantly based on efficiency, flexibility and location. But it is difficult for owners to cover fixed costs with such low load factors.

Closures and mothballing of coal and gas capacity over the next two years will be a key driver of a more structural recovery in load factors. Commodity price evolution will also be important.

But in the meantime, Spain faces a conundrum The market needs CCGT flexibility across the 2020s, firstly to backup increasing wind & solar intermittency and secondly to offset swings in hydro output. This is the case even under the most optimistic scenarios of future battery deployment. Yet under current market arrangements it is not clear how CCGTs will earn an adequate margin to remain open.

That is the essence of the challenge facing both CCGT owners and policy makers.

Building a Spanish CCGT investment case?

The suspension of capacity payments may mark the point of capitulation for many CCGT owners, after 5+ years of poor margins. Naturgy’s decision to pull 2GW of capacity offline is likely to be followed by other asset sales, mothballing or closure decisions.

CCGT ownership in Spain is dominated by utilities with transitioning business models. Boardroom focus is shifting away from conventional thermal generation portfolios towards renewables and energy services. This smooths the way for sale of thermal assets, along with the fact that asset values have already been written down.

The investment case for prospective asset buyers is focused on acquiring cheap options. CCGT capacity assets may transact at less than 50 €/kW (vs new build costs of 500 €/kW+). While that may seem like cheap capacity in a market that has a structural requirement for CCGT flex into the 2030s, some of the 26GW of assets are worthless (i.e. margins don’t cover fixed costs).

The challenge is paying a ‘premium’ for CCGT assets that fairly reflects the value of asset optionality (or flexibility). This premium does not just include the acquisition cost. It also involves paying annual plant fixed costs (~20 €/kW). Defining adequate risk adjusted margins above fixed costs is not a simple exercise.

Building a robust investment case comes down to:

- Identifying unique asset benefits (e.g. ramping flex, lower variable & start costs, locational benefits, additional margin streams)

- Minimising fixed costs i.e. ‘cost of carry’ of asset optionality (e.g. via renegotiating maintenance contracts & cutting overheads)

- Understanding the evolution of the Spanish capacity mix (& associated uncertainty) and the impact of this on pricing and CCGT margin dynamics

- Ability to quantify the value distribution of CCGT optionality i.e. flexibility to respond to price fluctuations (via probabilistic dispatch optimisation modelling)

- Understanding Spanish regulatory risk and developing an associated management / diversification strategy.

An environment of distressed asset owners and capitulation creates opportunities. But in a nutshell, it comes down to the combination of getting the right assets at the right price. That combination is starting to look more achievable given a growing queue of owners looking to exit.