Blog Content Types: Featured Article

Hydrogen’s path into the gas supply chain

5 chart focus: European gas market

5 chart focus: Continental European power

Revenue stacks for the ‘big 5’ flexible assets

UK capacity market ‘back in play’

Valuing European LNG regas capacity

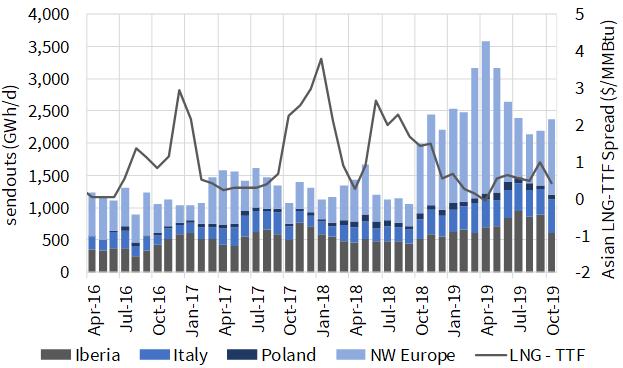

European regas capacity is back & flashing on the commercial radar screen. The obvious explanation for this is a jump in terminal utilisation over the last 12 months as Europe absorbs surplus LNG.

There are however other structural drivers behind a renewed interest in regas capacity. Liquid hub access is becoming more important as a means for portfolio players to optimise & hedge increasingly complex LNG portfolios. At the same time cargo diversion flexibility is increasing, supported by a wave of new US export capacity coming online across 2019-21.

This renewed focus on regas has been reflected in our client work across the last year. We have been engaged by several LNG portfolio players to analyse the valuation of regas capacity & its portfolio impact. We have also been engaged by terminal owners to look at valuation from a capacity monetisation perspective.

As a result of this work we have developed a framework for regas capacity valuation which we summarise in today’s article. We focus on NW Europe regas with liquid hub access (e.g. UK, NL, FR, BE, DE), but the principles apply more broadly to less liquid access points.

Chart 1: European LNG imports and JKM vs TTF price spread

Source: Timera Energy

Regas value 101

Regas capacity is an option to regasify an LNG cargo and deliver it into a liquid hub.

Take a simple example of a LNG portfolio that owns a NWE LNG spot cargo off the coast of NW Europe. In the absence of regas capacity access, this cargo can only be monetised via sale of the spot cargo (at a relatively illiquid NWE spot price). If the cargo owner has regas capacity, the cargo can alternatively be monetised at a liquid hub (TTF or NBP).

If you want to get technical, regas capacity is essentially a strip of options on the spread between TTF and NWE LNG spot prices.

Regas capacity does not just support the monetisation of spot cargoes, but also the hedging of forward exposures. Take a US export supply contract as an example. This represents a strip of forward cargo exposures with diversion flexibility (e.g. to Europe or Asia). Regas capacity access allows these exposures to be hedged on a forward basis against the liquid TTF (or NBP) forward curve and then optimised or re-hedged over time against the less liquid JKM curve.

4 building blocks of regas value

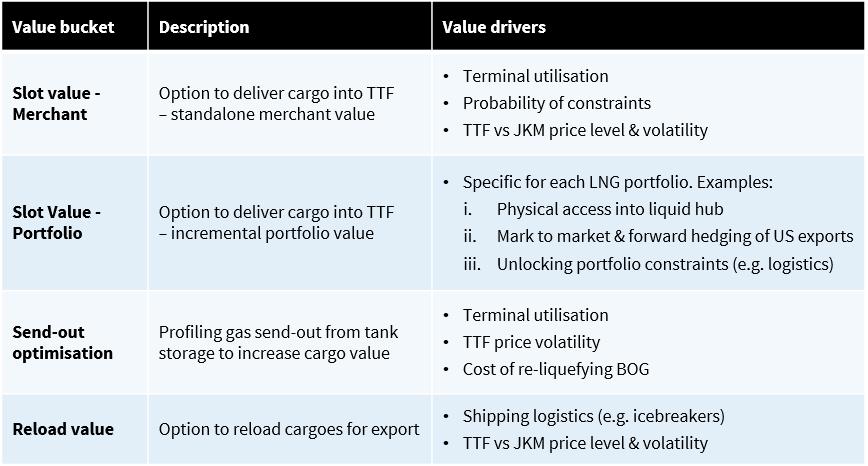

In order to value regas capacity it is useful to deconstruct value into components. Diagram 1 summarises four building blocks of value.

Diagram 1: Regas capacity value components

Source: Timera Energy

1.Merchant slot value

First we consider the merchant or standalone value of regas capacity, in the absence of any other portfolio components. Merchant slot value is currently limited by the fact that there are no structural constraints around NW European regas capacity access. Across UK, Netherlands, France & Belgium there are plenty of spare regas slots under normal market conditions.

Merchant slot value is a function of the expected probability of slot utilisation multiped by the price (or value) of regas capacity when it is utilised. For regulated terminals this price is the regulated tariff. For TPA exempt terminals, regas slot pricing is also driven by regulated tariff levels as these represent the opportunity cost of alternative terminal access (in the absence of any NW European regas constraints).

Temporary regas capacity constraints can occur. For example, supply outages caused some UK regas capacity constraints in 2018 (during the ‘beast from the east’ cold weather pattern). High import volumes have also seen GATE constrained during periods in 2019. These constraints can cause merchant slot value to rise above regulated tariff levels. However limited secondary trading of regas slots, means this incremental value typically accrues to LNG portfolios with the flexibility to bring FOB cargoes into constrained terminals (see 2. Portfolio slot value below).

Over the next decade, the volume growth of flexible LNG is set to substantially outstrip planned investment in new European regas capacity. That means the probability of European regas constraints is likely to rise as (i) terminal utilisation increases with import volumes and (ii) regas capacity headroom declines. This structural tightening is an important driver of recovery in regas capacity value in the 2020s.

2.Portfolio slot value

The primary driver of a company’s willingness to pay for regas slots is the incremental value that regas creates when added to an LNG portfolio. Regas capacity can add optionality (e.g. facilitating diversion) or unlock constraints (e.g. access to liquid hub prices). These sources of value can be substantial given the limited liquidity & complex supply chain logistics of the LNG market.

Lets consider a practical example of portfolio value. A number of Asian buyers have US export contract volumes (e.g. JERA, Osaka Gas, GAIL, Sumitomo). These companies place significant portfolio value on physical access to TTF or NBP liquidity. This value is driven by the ability to manage supply contract risk and mark to market forward cargo exposures against a liquid curve. But it also allows value creation from forward hedging of diversion flexibility based on fluctuations in TTF vs JKM price spreads.

The challenge in quantifying portfolio value is that it is heavily dependent on the bespoke components of an individual portfolio. There is added complexity as to whether the value created by adding regas actually accrues to the regas slots or to other existing components of the portfolio e.g. flexible supply contracts.

However one thing is clear. A portfolio modelling capability is required to effectively quantify the incremental value of adding regas capacity. This capability allows the analysis of the interaction between evolution of pricing dynamics and portfolio exposures. We provide a simple illustration in the blue box below.

- Send out optimisation value

Value can be created by optimising the profile of send out from tanks at regas terminals against market prices. Send-out is effectively a single direction storage option (with no injection rights) and can be valued as such with stochastic storage modelling techniques.

However there are practical limitations on the value of send out optionality. It is typically limited by operational constraints e.g. requirement to retain inventory to keep tanks cool during periods of low utilisation or to empty tanks quickly to free up capacity for incoming cargos during periods of high utilisation.

It is not so often that tanks are in ‘sweet spot’ inventory levels e.g. 40-60%, and the value of holding high levels of inventory is also usually eroded by boil off gas (BOG) losses. Terminals with the capability to re-liquify BOG can have higher send-out value as this removes the requirement to manage low inventory levels and loss of BOG.

4.Reload value

Some terminals have the capability to reload cargoes. This can allow capacity holders to circumvent destination clause restrictions in supply contracts. It can also create value via alleviating logistics constraints e.g. the reload of cargoes from Yamal icebreakers at NW European terminals allows more efficient deployment of these vessels on artic routes.

Both these sources of value are driven by contractual or logistical dynamics within specific portfolios. This again points to a LNG portfolio model to effectively value reload optionality.

Enabling reload in regas terminals typically involves low capex. There are also relatively low barriers to entry. These factors effectively cap the amount of value that can be assigned to reload optionality in the longer term.

Pulling component values together

Regas slots suffer from a lack of price transparency, given there is no liquid secondary market for capacity. The valuation of regas capacity is further complicated by the fact that it needs to be quantified as part of a company’s broader portfolio strategy. The value that slots create for an Asian buyer may be very different in size and nature to that for a commodity trader.

However the analytical approach to valuing regas capacity is becoming more consistent. And this focuses on using a portfolio valuation modelling framework to practically analyse how regas slots create value via adding portfolio optionality and unlocking constraints. We provide further details on this in the briefing pack linked in the blue box below.

| Briefing pack: LNG portfolio value Timera briefing pack with approaches and case studies on identifying & capturing LNG value: Gaining an edge |

Charter rate surge shakes LNG market

LNG vessel spot charter rates have exploded since late September. If you are not in the business of chartering boats you may be tempted by an obvious question… ‘who cares?’

Spot charter rates have much broader market implications. The delivery of LNG cargoes is increasingly being optimised against spot price signals. Margin opportunities in moving LNG between regions depends on the cost of transportation. This means that shipping cost differentials have become key drivers of LNG flows & regional price spreads, as well as LNG portfolio value opportunities.

LNG flows have also been the primary driver of European gas market supply & demand dynamics across the last year. Forward market pricing points to this continuing across 2020-21. And European LNG import levels also determine the volume of surplus gas absorbed by European power markets via switching.

The upshot of this interconnected market logic is that quite a few people care what happens to charter rates. In today’s article we take a look at why rates have soared and what the market impact may be.

The charter rate rollercoaster

Most of the global LNG shipping capacity is under term charter to portfolio players. This means there is typically only relatively small volumes of capacity available on a spot basis e.g. for traders wanting to take advantage of arbitrage opportunities.

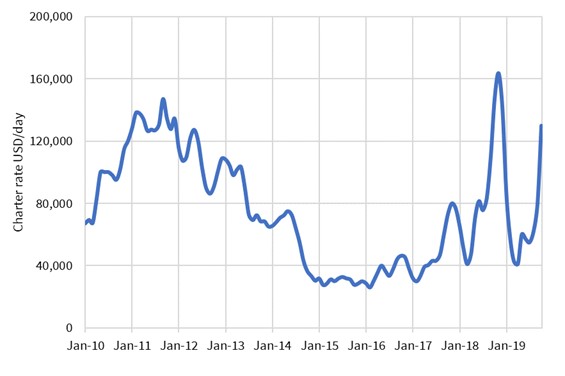

Limited spot liquidity exacerbates the price impact of any adjustments to supply and demand. This can be seen in Chart 1 which shows the evolution of spot charter rates this decade.

Chart 1: LNG spot vessel charter rates

Source: Timera Energy

The Fukushima disaster in 2011 caused a sharp rise in charter rates as incremental shipping capacity was required to move large volumes of LNG to Japan as nuclear plants closed. Tightness then eased into mid-decade as a wave of new vessels were commissioned.

Charter rates surged again in 2018 as new liquefaction projects came online and cargos were diverted from Europe to Asia (with longer average voyage times). This was a short lived phenomena as Asian demand softened in Q4 2018 and large volumes of LNG flowed back into Europe.

The 2019 charter rate surge

Spot charter rates have quickly surged from below $50k per day this summer to above $130k per day by mid October. This translates into roughly 1.20 $/mmbtu cost increase for a spot charter voyage from US to Asia (assuming round trip costs).

So what is behind the move? A key catalyst has been the US sanctions slapped on state-owned Chinese shipping company Cosco for breaching Iranian oil sanctions. This has effectively ‘blacklisted’ a number of vessels operating under long term charter e.g. from Tangguh in Indonesia, Bintulu in Malaysia and the North West Shelf in Australia. The sourcing of replacement vessels in the spot market has driven up rates.

Four icebreakers used to transport LNG from the Yamal peninsula were also impacted by sanctions, given a Teekay JV with a Chinese company owned by Cosco. But this issue was resolved last week via an ownership restructure that circumvented the sanctions.

The Cosco issues have grabbed headlines but there are a couple of other factors behind the recovery in charter rates:

- Contango: Both TTF and JKM forward curves are in steep contango (rising forward prices) across the next two months. This reflects market normalisation from very weak prices across the summer. Curve contango is encouraging cargo owners to use LNG vessels as floating storage i.e. you get paid for delaying delivery of the cargo given rising prices.

- Distances: As new US export volumes come online, they are increasing average shipping distances, particularly if the LNG is flowing to Asia. This effectively increases utilisation of the global vessel fleet, acting to tighten supply and support charter rates.

Market impact: 3 factors to watch

The market impact of higher charter rates depends on whether the current surge is temporary and if not how higher rates will impact LNG flows. Three factors to consider:

- Work arounds: The Teekay solution for the Yamal icebreakers is a good illustration of the commercial incentives to develop work around solutions to allow vessels to continue operating. If this logic extends to other vessels impacted then the Cosco element of the problem may be a more temporary impact.

- Asian demand: Given tightness in the shipping market is linked to distances, the volume of cargoes flowing to Asia is important. Asian LNG demand has been weak so far across 2019, but may pick up into winter. The extent to which this happens should support charter rates into 2020. If demand remains weak then higher volumes of LNG are likely to continue to flow into Europe.

- US export economics: Netback prices on US export supply are impacted by higher charter rates. Higher rates increase US LNG shut in price levels. They also favour the economics of moving LNG to closer markets (e.g. Europe vs Asia).

We will keep an eye on the evolution of charter rates and the knock on impact on markets via our Snapshot column.

LNG market evolution in 5 charts

Several key structural market trends are reshaping the way that LNG is transacted.

The US has emerged as a key provider of destination flexible supply, with almost 100 mtpa of committed export capacity. Destination clause restrictions in existing supply contracts are also being relaxed or removed, helped by the negotiating balance swinging in favour of buyers in a well supplied market and competition authorities declaring these clauses anti-competitive.

Increasing demand uncertainty in traditional LNG markets is eroding appetite for long term and inflexible contracts. This uncertainty is being caused by evolving policy initiatives (e.g. the phasing out of coal & nuclear in Sth Korea), growth of renewable generation, ongoing market liberalisation and volume risk around Japanese nuclear restarts.

The rise of LNG portfolio players is rapidly eroding the traditional producer to supplier contracting model. This trend is being reinforced by the aggressive growth of commodity traders (e.g. Vitol, Trafigura & Gunvor) who are boosting market liquidity and shorter term contracting.

Reinforcing the trend to shorter contract durations, the next wave of LNG supply that is now taking shape is featuring the rise of equity offtake models (as opposed to long term contracts). The recently FID’d LNG Canada project is a good example, where project developers will market their own equity share.

In today’s article we look at 5 charts that summarise the ongoing impact of these trends. The charts draw on data from the IEA’s recently published ‘Global Gas Security Review’.

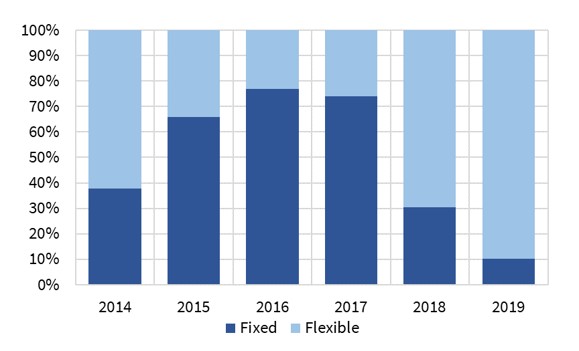

Chart 1: Growth of flexible destination clause contracts

Source: IEA

Chart 1 shows the level of destination flexibility in supply contracts concluded over each of the last 6 years. It includes contracts linked to FID’ed projects as well as portfolio sourced contracts.

The higher levels of flexibility in 2014-15 reflect the first wave of US export project FIDs. From 2017-19 a clear trend can be seen away from traditional fixed delivery point DES contracts towards greater diversion flexibility.

Contract duration has been falling in parallel, also reflecting the need for greater flexibility (although the 2018 FID of LNG Canada on an equity offtake basis somewhat skews recent stats). As long term DES contracts roll off, they are being replaced by destination free, shorter duration contracts. For example JERA sourced a 3 year, 2.5mt/year contract when its 15 year, 4.8 mt/y contract with Petronas ended in 2018.

Chart 2: Growth of gas – to – gas indexation

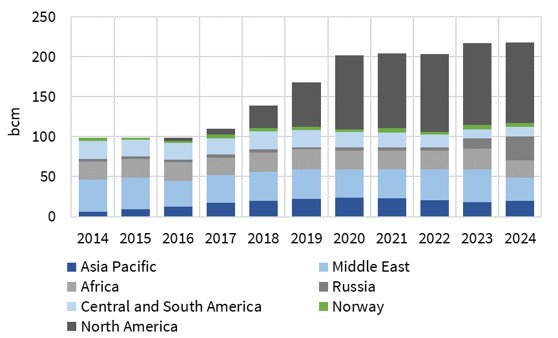

Source: IEA

Chart 2 shows the volume of gas indexed LNG supply volumes across the 2014-24 horizon (again including new projects and portfolio deals). A clear increase in gas indexation can be seen, with contract prices linked to traded hubs (e.g. Henry Hub, TTF, JKM) as opposed to traditional oil-indexation.

The rise of gas indexation reflects an increasing trust in gas price benchmarks as liquidity grows. It also reflects increasing mismatches between oil-indexed and end-user prices. There have been reports of coal indexed Asian LNG contracts, which is more logical than oil.

Chart 3: Growth of the portfolio player

Source: IEA

The chart shows LNG contracts without a specific source (export contracts) or destination (import contracts). This provides a clear illustration of the rapid growth in the role of LNG portfolio players and the resulting breakdown in traditional producer source to supplier destination contracting.

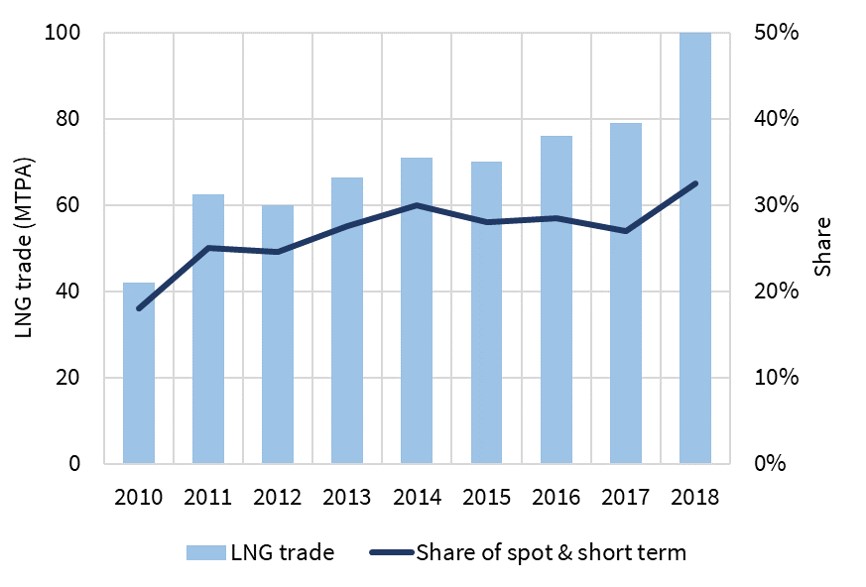

Chart 4: Spot & short term share of total LNG trade

Source: GIIGNL, Kpler

As portfolio players disaggregate ‘bought’ from ‘sold volumes it creates a more complex portfolio optimisation & value management challenge. This is also creating a growing requirement for hedging, balancing & adjustment actions in the traded market, which is supporting liquidity growth.

This can be see in the rise in spot & short term LNG trade in Chart 4. The rapid increase in flexible US export volumes coming online across 2018-20 should support this trend.

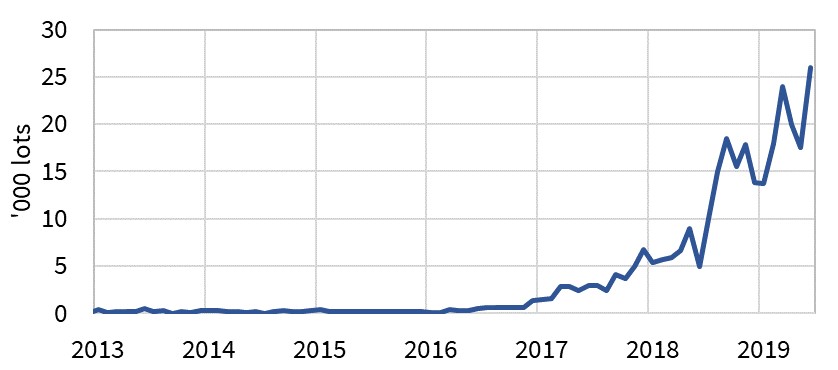

Chart 5: JKM swaps cleared through CME & ICE

Source: CME, ICE

LNG portfolio management is not just a spot problem. It is increasingly involving the forward hedging of portfolio exposures with financial products e.g. the hedging of gas indexed & diversion flexible US LNG contracts against TTF and JKM forward prices.

Chart 5 shows the rapid growth in volumes of JKM swaps across the last two years. Portfolio players are using swaps and futures to lock in prices on forward delivery volumes. These hedge positions can then be adjusted and optimised as market prices move, to manage risk and create value.

Five takeaways

In summary, the charts show 5 trends that are set to continue to shape the LNG market.

- Contracts are becoming more flexible & shorter duration

- Gas indexation is rising and replacing oil

- The role of portfolio players is growing, disaggregating source from destination

- As a result, spot & short term trading of LNG is growing…

- … and portfolio exposure management is also driving an increase in forward liquidity

These trends increase the complexity of the LNG market. But they also increase the ability to create value and manage risk.

The decarbonisation tipping point?

‘tipping point’: the point at which a series of small changes or incidents becomes significant enough to cause a larger, more important change.

Carbon dioxide concentration in the earth’s atmosphere has risen 40% since the industrial revolution. Half of that increase has occurred since 1980. And global carbon emissions continue to steadily rise.

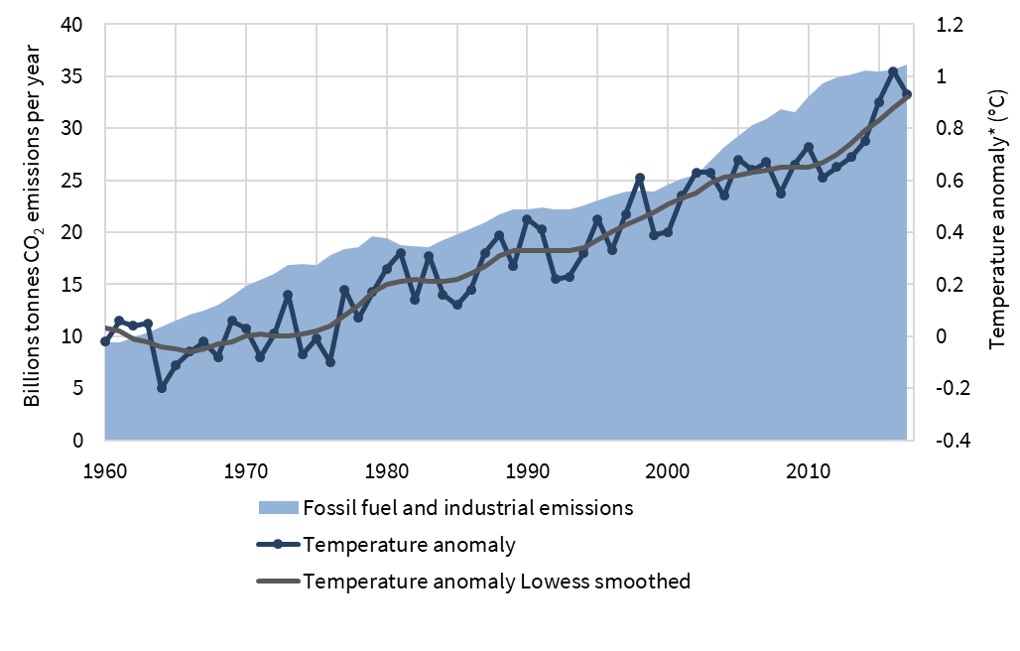

There is clear scientific evidence of the link between rising carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere and increasing average air & sea temperatures (see Chart 1). There is also growing evidence of feedback loops (e.g. melting sea ice) and accelerating changes in climate patterns, although these are more difficult to measure.

Scientific evidence is increasingly pointing to the fact that we are past the tipping point with respect to climate change.

The geopolitical implications of climate change are also coming into sharper focus. For example, the risks of large scale population displacement, decreasing availability of water & arable land and growing conflict for resources. This increases the incentives for action.

So are we also reaching a tipping point in terms of a decarbonisation response?

This is the first in a series of two articles on a decarbonisation tipping point. Today we set out 5 drivers that suggest a tipping point could be upon us. Then in a second article we will look at the impact of more rapid decarbonisation on energy companies & portfolios.

Chart 1: Carbon emissions vs global average temperatures

Source: Global Carbon Project, NASA

5 drivers that suggest a decarbonisation tipping point is near

1.Lack of progress

Global carbon emissions rose 2% in 2018, the fastest pace for 7 years. This is despite plunging costs & rising volumes of renewable energy. The simple reason is that action on decarbonisation is being outpaced by emissions growth from rising energy consumption caused by population & economic growth.

The global population is increasing by about 1 million people every 4 days. Think of a mid-sized new city of energy demand created each week (as well as the other resources required to develop & support it).

In addition to population growth, economic growth in developing nations is increasing energy consumption of the existing population. For example, 88% of the Chinese population lived below the poverty line in 1980 compared to less than 1% in today’s urbanised China. Energy consumption at the margin is still predominantly supported by fossil fuels.

The challenges of emissions reduction have seen the problem largely kicked down the road over the last 20 years. But scientific evidence is increasingly pointing to a window for action over the next 10 years in order to avoid more severe climate disruption. Discount factors are no longer enough to shrink the problem into the future.

2.Fiscal tailwinds

Austerity is dead. Long live Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). There is growing momentum on both sides of politics to abandon austerity for fiscal expansion. Economists as well as politicians are swinging behind fiscal spending, led by central bankers who are confronted by the limits of monetary policy in propping up economic growth.

The basic premise of MMT is that in a low inflation environment, deficits don’t matter so long as a country can print money in its own currency. Modern Monetary Madness? Maybe… but in a world struggling against powerful demographic & technology driven disinflationary forces, MMT is a seductive economic narrative to justify political spending.

Countries with this ability to monetise their own debt (e.g. US, Europe, Japan, China) look increasingly likely to embark on large fiscal spending programs. Decarbonisation is an obvious spending target, as evidenced by the rise of the ‘Green New Deal’ in the US.

The costs of large scale decarbonisation are also falling with rapidly declining borrowing costs. Interest rates on government & corporate debt have plunged in 2019, continuing a 40 year downtrend. There is now more than $15 trillion of negatively yielding debt worldwide (i.e. lenders paying borrowers to take their money away). The combination of targeted fiscal spending & low rates may create powerful tailwinds for decarbonisation.

3.Business is engaging

There has been a subtle but important shift of big companies behind decarbonisation over the last 2-3 years. This is in part in response to the rising importance of climate change to customers. Global giants such as Google, Microsoft and Unilever are decarbonising their business models at a much faster pace than policy requires. Many large companies have now set (or already achieved) 100% electricity decarbonisation targets and are looking to expand on these.

But there are much larger economic incentives in play. Large tech & consumer companies see growing fiscal, technology & decarbonisation tailwinds as an opportunity to disrupt traditional energy companies (e.g. utilities & oil majors) & supply chains. Energy companies are also actively repositioning for growth from decarbonisation, as are engineering firms tackling resilience projects (e.g. sea walls).

This trend of business support for decarbonisation helps smooth the way for more aggressive policy action.

4.Generational mobilisation

Greta Thunberg, a 15 year old Swedish girl, started a one person ‘climate strike’ in August 2018. A little over a year later she was favourite to win the Nobel Peace Prize going into the ceremony last week (although it went to the Ethiopian PM) . What makes her impact larger than the many other people who have tried similar protests over the last 20 years? Timing would appear to be an important factor.

Whatever you think of Greta’s political influences, she symbolises the rapid mobilisation of a generation in a way not seen since at least the 1960s. 2019 has seen large youth climate protests on an almost daily basis, involving millions of people from a broad range of countries, wealth levels and political backgrounds.

This organic climate movement is hard to pin down. It seems to capture a complex (and sometimes inconsistent) mix of issues, politics & proposed solutions. But there is one common theme that binds the movement together: a demand for climate action now.

5.US leadership?

The Democrats are now odds on favourites to win the White House in 2020. Trump’s odds of winning are slipping with the fortunes of his ‘greatest economy in history’ (he is now 11/8 to win a second term).

It is unclear which of the Democrat candidates will take on Trump. But fiscal expansion to support the Green New Deal is a prominent policy goal for all of the leading Democrats. A Democrat in the White House could see the full force of US innovation thrown behind decarbonisation.

Even in the absence of a Democrat President, there has been growing decarbonisation momentum at a state level. 16 states have now committed to 100% renewable or 100% carbon free targets by 2050. California (the 6th largest economy in the world) is playing a particularly important role in implementing policy change.

Clear US leadership on decarbonisation over the next five years would likely precipitate a rapid acceleration of the global response.

What does this mean for European energy?

We have become used to a relatively slow rate of progress on decarbonisation over the last 20 years. That could of course continue. There is still considerable inertia acting against rapid change.

But the five factors above are increasing the probability of a step change in decarbonisation response across the next 5-10 years.

Current trends point to this response being led by:

- Developed countries

- Europe (as a subset of developed countries)

- The power & gas sectors.

That means European power & gas markets are likely to be at the epicentre of global change. They are the low hanging fruit.

We consider the implications of accelerated decarbonisation on energy companies & portfolios in the next article.