‘Asian natural gas prices are four times prices in the US’. This is a striking statement that has got a lot of airplay over the last two years. Pronounced inter-regional gas price spreads sit in stark contrast with a relatively narrow global price range for the other global energy commodities, crude oil and coal.

Global price divergence in the gas market is a function of two main drivers:

- It is expensive to liquefy, transport and store gas as LNG.

- The LNG market is relatively immature, with a limited volume of destination flexible supply (flexibility is constrained by source to destination restrictions imposed by long term contracts).

Physical and technological constraints mean it will always be a more expensive business moving gas than oil and coal. But rapid growth in the LNG spot market, development of price signals and expansion of infrastructure will over time act to erode global gas price differentials.

Regional price drivers

Spot prices for natural gas delivered in July 2013 are shown in Chart 1 across different regions.

Chart 1: A July 2013 overview of global spot gas price benchmarks (USD/mmbtu)

Source: Waterborne, US FERC (prices as at 7th June).

There are distinctly different drivers of spot gas prices across different regions of the world. Regional pricing is best understood by grouping the markets illustrated in the chart into five regional zones:

North America is a market where gas pricing is driven by trading at the liquid and transparent Henry Hub (HH). Current HH spot price levels below $4/mmbtu, reflect the impact of a surge in unconventional shale gas production over the last 5 years. A rapid transformation from tightness to oversupply and a lack of export infrastructure has effectively left gas ‘trapped’ in the US market. But contango in the HH forward curve reflects a future of growing US exports and increasing production costs.

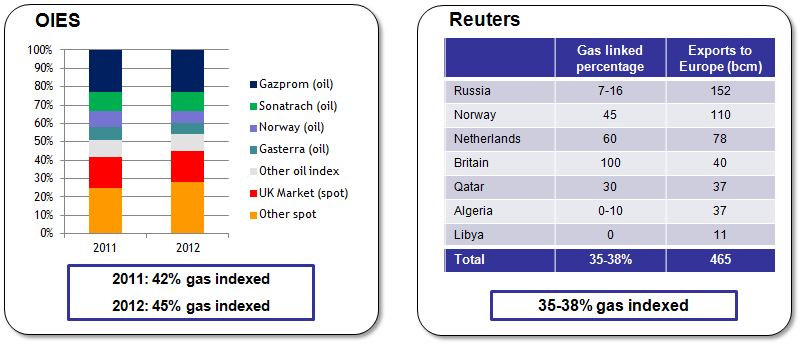

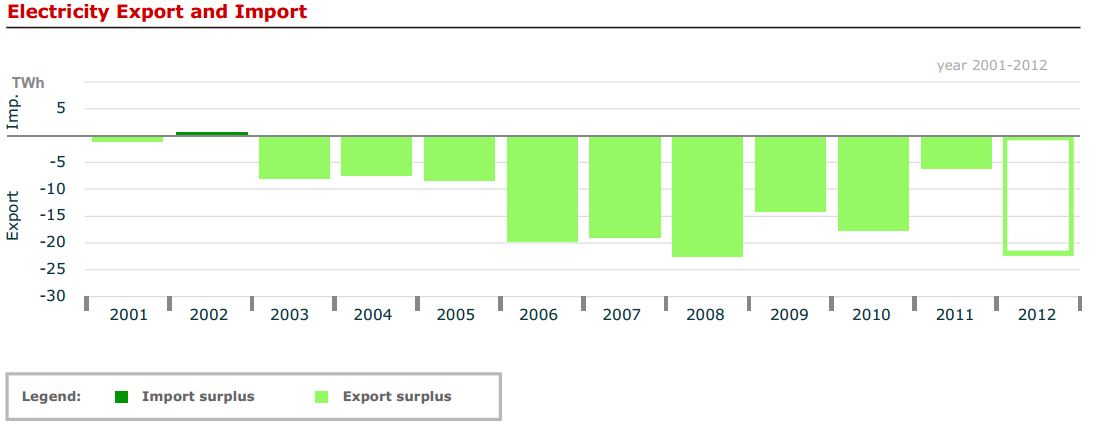

Northern Europe is also a market driven by liquid hub prices, primarily at the UK NBP, Dutch TTF and the German NCG. But unlike North America, hub pricing tends to remain within a band of oil-indexed pipeline contract prices. This reflects the dominance of these contracts in determining marginal price dynamics at European hubs.

Southern Europe is increasingly influenced by the larger and more mature Northern European market. The Italian market has largely converged with European hub prices. Spanish gas prices tend to be higher than those in Northern Europe to reflect the impact of oil-indexed contract prices and at times global LNG prices on marginal pricing. But the relative isolation of the Iberian peninsula will decline given new interconnection under development with France. European hub price convergence is likely to follow.

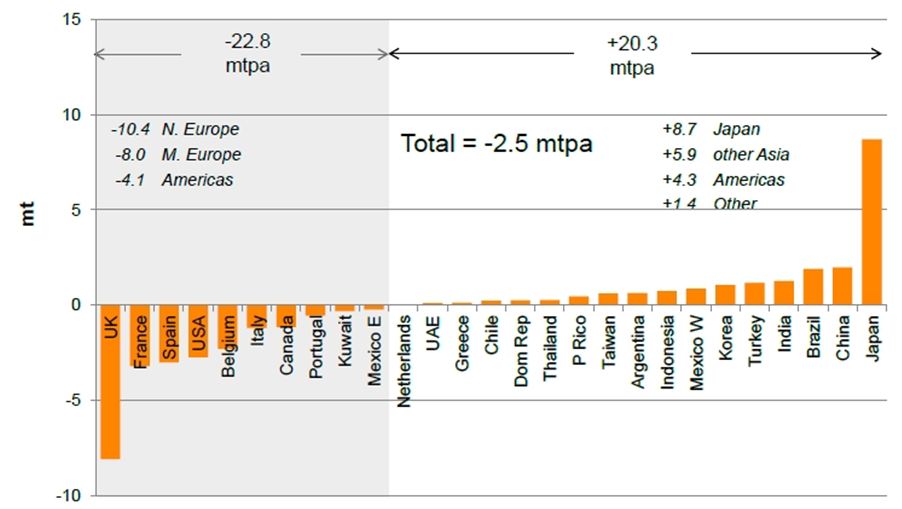

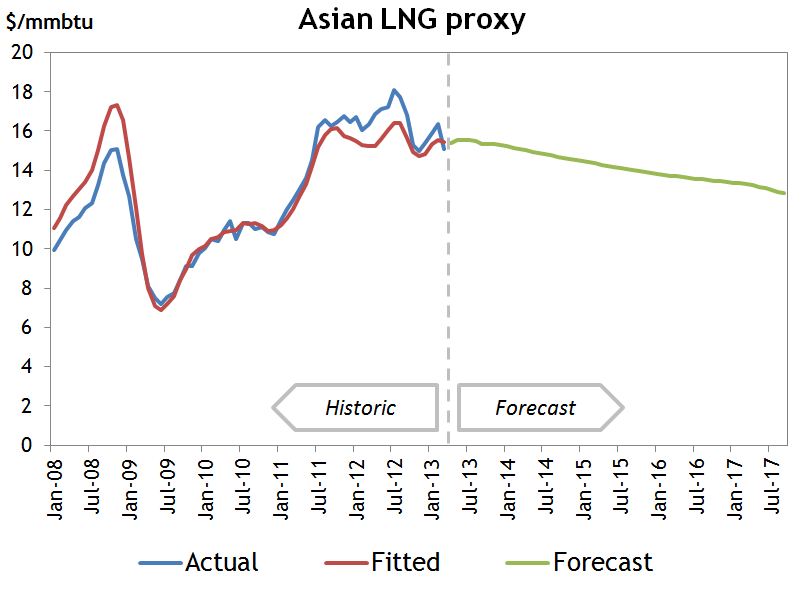

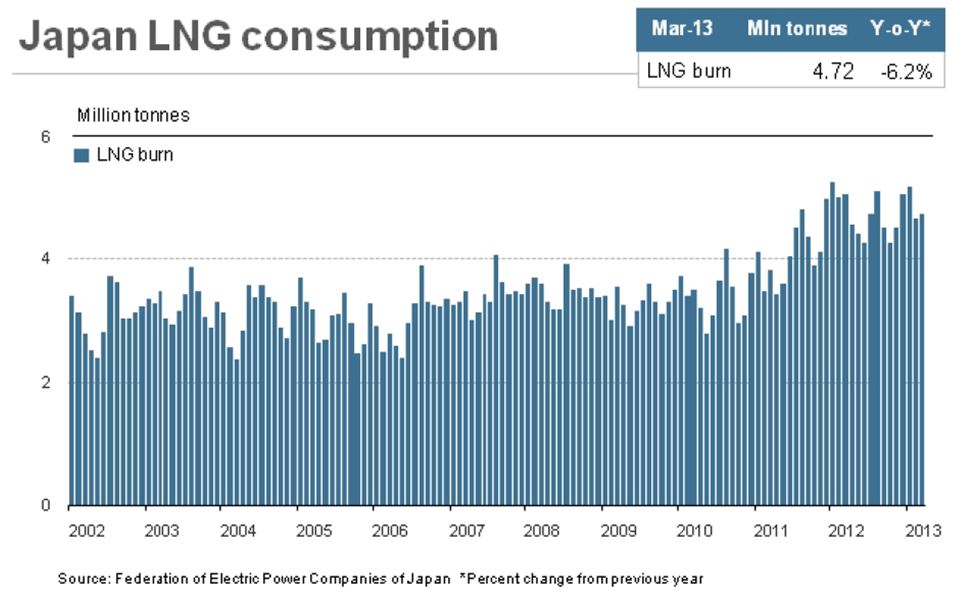

Asia is the key driver of LNG market growth. Most gas is delivered under long term oil-indexed contract prices, typically signed at a substantial premium to US and European hub prices. While oil-indexed LNG contract prices act as a loose anchor for Asian spot prices, substantial spot price swings are common. Asian spot prices typically trade within a range between a European hub price driven ‘floor’ and an Asian oil-equivalency driven ‘cap’. The prevailing spot price premium over Europe is a barometer for how much spot supply Asia needs to attract to satisfy demand.

South/Central America is a relatively small gas market by volume. But buyers in countries such as Argentina, Brazil and Mexico can have a disproportionate impact on global spot pricing. Buyers tend to have low levels of contract cover and often purchase LNG in ‘blocky’ parcels in the spot market or via shorter term tender. In doing this they are typically competing for available LNG against Asian buyers. Hence spot price levels tend to trade within a band of Asian spot prices. Perhaps the greatest global pricing anomaly at the moment is the size of the premium that South/Central American buyers are paying over US gas prices.

What does the future hold?

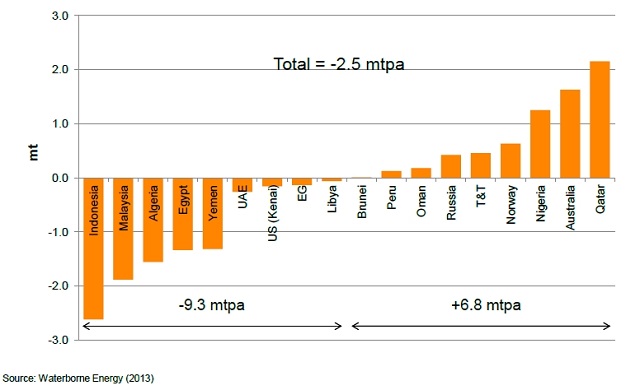

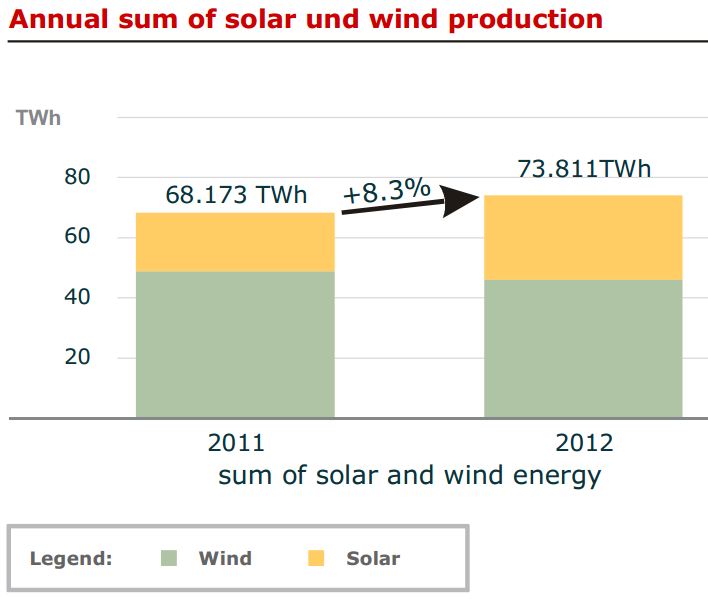

As with most commodity markets, the market consensus view of future outcomes is heavily influenced by current market conditions. The prevailing tightness and regional price divergence across the global gas market reflects a post-Fukushima world of strong Asian demand and a temporary hiatus of new liquefaction projects. While these conditions are likely to remain until 2015, the second half of this decade may be a very different picture.

Pricing beyond 2015 will be driven by the balance of market power in the next phase of LNG market expansion. Large new liquefaction projects in Australia, Canada and East Africa are looking for long term oil-indexed buyers to underwrite capital costs. These projects are competing against US export projects that enable buyers to source Henry Hub indexed gas. To a large extent the next phase of LNG market expansion will depend on the scale of a much anticipated surge in Chinese import demand. But the drivers behind Chinese LNG demand are complex and any significant disappointment in demand growth could well tip the gas market back into a state of oversupply later in the decade.

The global gas market may currently be characterised by regional price divergence. But with growth in the LNG spot market and the development of new infrastructure, structural price premiums like the one between the US and Asia will be eroded. The cost of moving and storing gas will prevent global gas market convergence to the extent it has occurred in oil and coal markets. But as the LNG market evolves, it is transport cost differentials rather than structural price premiums that will drive inter-regional price spreads.