This is the first in a series of articles on commercial considerations in the negotiation of long term energy contracts, written by Nick Perry.

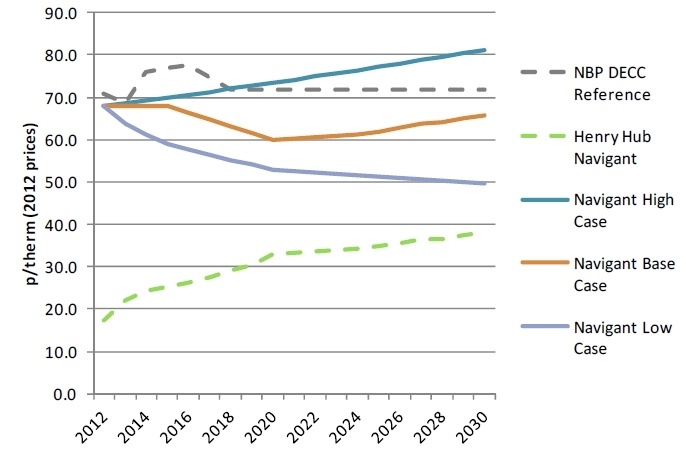

The European energy industry is navigating a period of intense re-negotiation of long term contracts. Rapidly changing market price dynamics have resulted in large swings in contract value and exposed unintended consequences of original terms and conditions.

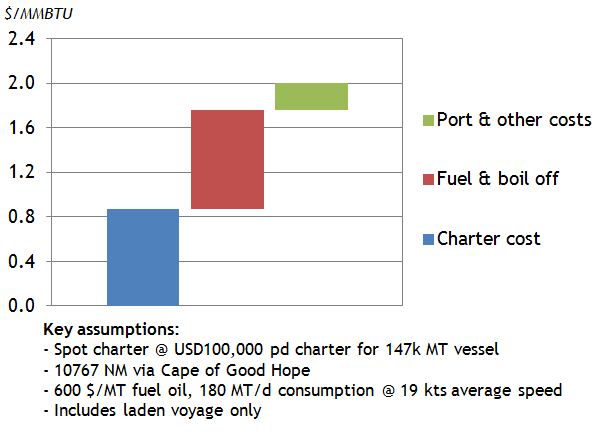

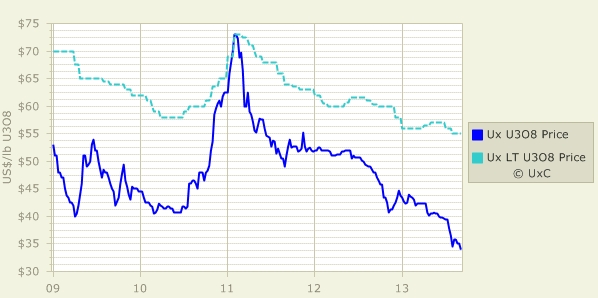

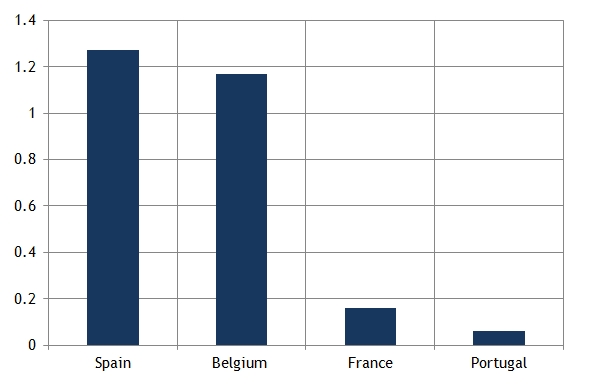

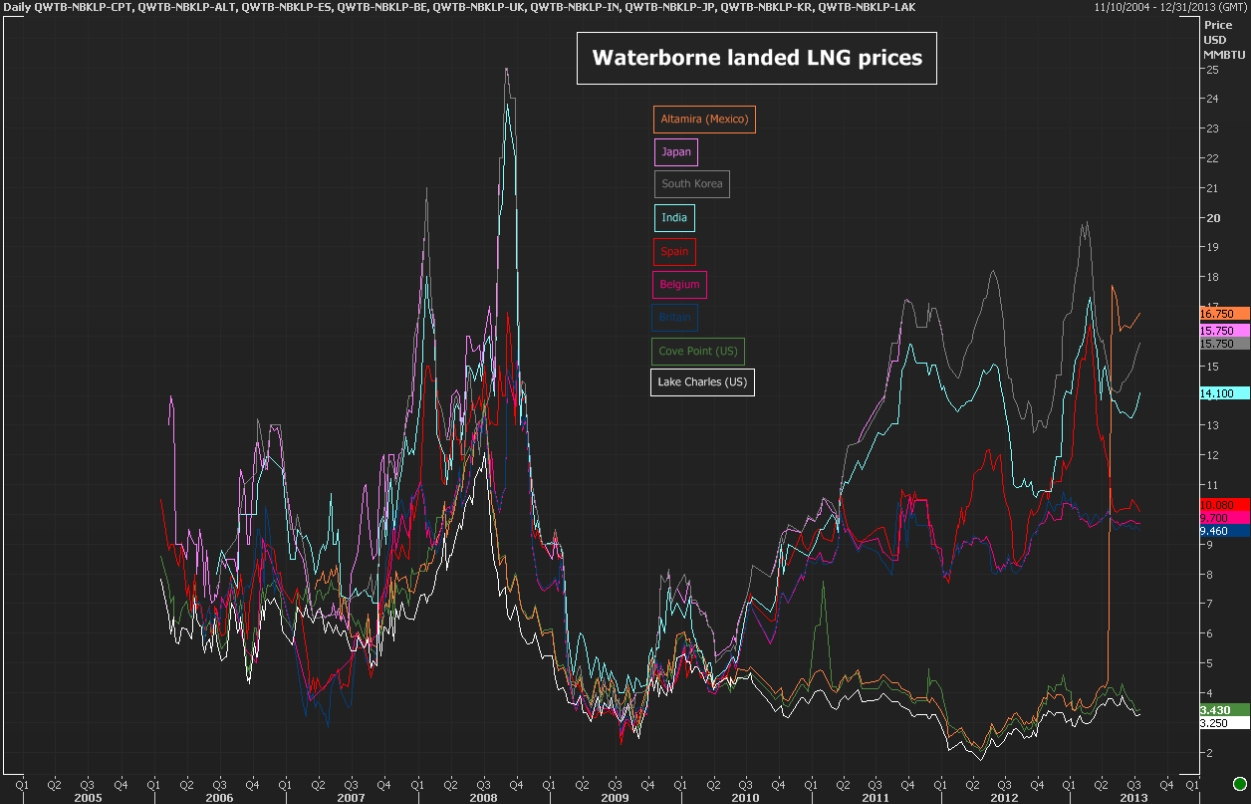

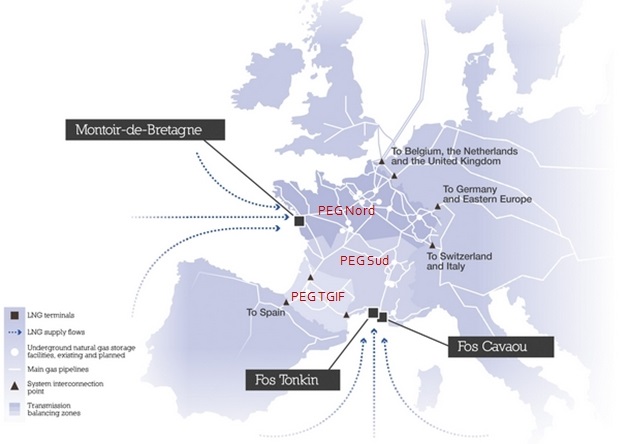

The outcomes of gas supply contract negotiations with Russia and Norway are having a substantial bearing on the financial viability of a number of European energy companies. At the same time, LNG supply contracts are being redrawn to reflect the impact of changing price dynamics and the increased value of diversion flexibility in a post-Fukushima world. In the power market, long term tolling contracts have been transformed by a sharp fall in spark spreads, lower load factors and an increase in plant flexibility requirements.

Long term contracts (LTCs) of large volume, long duration and high nominal value are widespread in the energy business. But the greatest absolute (mark-to-market) value is usually to be found when, after several years, an LTC becomes significantly in-the-money for one party, and correspondingly out-of-the-money for the other. In such circumstances, commercial creativity allied to good analysis and negotiation skills become critical factors for turning destructive win-lose stasis into positive win-win dynamics.

In this first article of our series on long term contract negotiation, we consider how these dynamics can be identified and fruitfully exploited for significant added value.

Price risk is the primary driver of contract value shifts

When a forward contract is first transacted in a liquid market, its absolute mark-to-market (MTM) value is usually close to zero for each party. Liquidity and transparency combine to minimise the chances of there being any large sums lying around on the negotiating table. This is generally the case even when liquidity and transparency are only partial. For price-takers in a market, the initial MTM may even be (slightly) negative when the deal is struck.

Good negotiators can often find ‘win-win’ ways to create positive initial value for both sides; for example, when they are able to arbitrage different costs of capital or diverging assessments of extrinsic value. The more ‘plain vanilla’ a forward contract, the less likely there is for a genuine win-win to be available but conversely the more complex the deal, the more likely it is to be possible.

Even so, initial contract MTM values will be small, perhaps even very small, relative to the nominal sums involved. (Parties that claim to have created large positive initial value are generally marking the contract to their own portfolio or – worse still – to their forecasts of future spot prices.) This is not to find fault with the transaction, which may represent a very sound hedge, for example, or a satisfactory liquidation of a physical position; or even a speculative open position taken on with full understanding of the potential downside. For a market-maker or arbitrageur, a small positive value on an individual deal may represent exactly what they are in business to capture, transacting small positive gains continually, in high volume and at low risk.

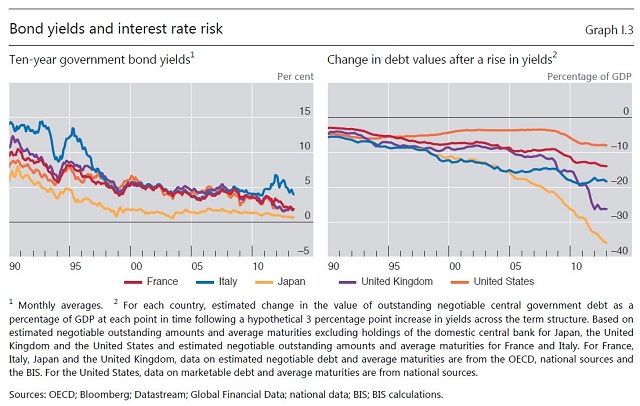

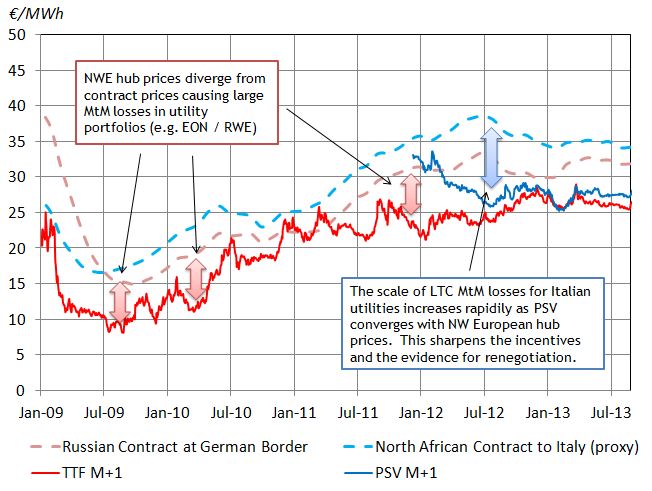

However, the MTM of unhedged large deals can evolve significantly away from their initial small value – in either direction. This of course is Price Risk, the primary category of market risk, and is nowhere more acute than in energy, where volatility is high and long-term price shifts can be dramatic. In order to illustrate this point, it is useful to consider a simple case study looking at the impact of the rapid convergence of Italian PSV and North West European hub prices.

Case Study: PSV convergence and Italian supply contracts

Large European gas suppliers (e.g. E.ON, RWE) suffered sharp losses in 2009-10 as the financial crisis took hold. Gas hub prices plunged below long term oil-indexed contract prices and a rapid fall in gas demand left suppliers long gas against take or pay obligations.

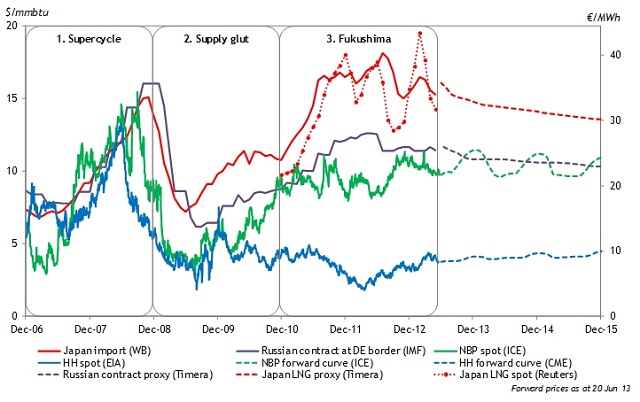

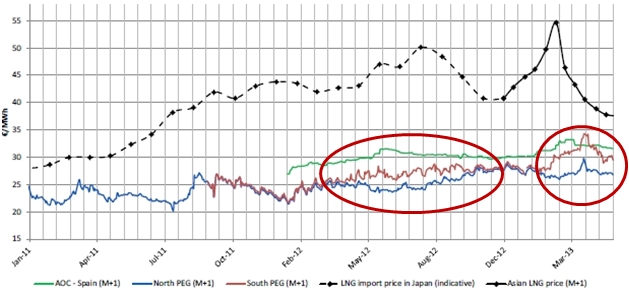

Italian suppliers were somewhat insulated from the trouble in northern Europe as the illiquid PSV hub continued to move in line with oil-indexed contract prices. However market events suddenly turned against Italian suppliers in 2012. The release of capacity on the TAG pipeline allowed the flow of surplus gas from Baumgarten into the Italian market, resulting in the rapid convergence of PSV and NW European hub prices. The scale and pace of this convergence is illustrated in Chart 1.

Chart 1: Hub vs oil-indexed prices and 2012 PSV convergence

Source: LEBA, IMF and Timera Energy

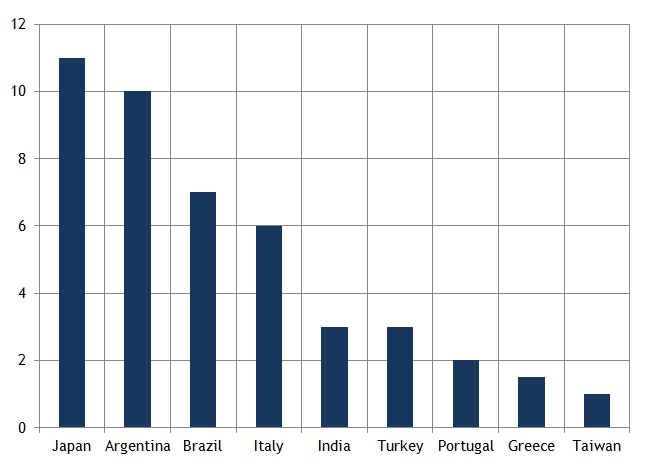

The plunge in PSV hub prices has become a key factor impacting renegotiation of a number of Italian supply contracts. ENI has the largest exposure to long term oil-indexed supply contracts in Italy. Although ENI’s losses from PSV convergence have been painful, they have been the catalyst for some favourable contract renegotiation outcomes. ENI has not only gained significant contract price concessions from Gazprom since 2012, but has renegotiated supply contract take or pay levels and indexation to reduce portfolio risk. Edison, another big Italian gas buyer, has also used the PSV price move as leverage in successful contract price renegotiations with Rasgas (LNG supply into Rovigo) and Sonatrach.

As is often the case, contract price has been the primary driver behind renegotiation. However negotiations have focused on concessions around a much broader range of contract parameters, e.g. spot indexation levels and volume flexibility, as parties try to re-optimise contract terms for changing market and portfolio conditions.

Approaching the negotiation table

Rightly, the first considerations for a company identifying part of its portfolio as having high MTM will be:

- how does this sit in terms of Price Risk, and in particular, does it represent a hedge for a correspondingly out-of-the-money portfolio component? If so, the value and commercial integrity of the in-the-money deal will need to be defended purposefully, leading to …

- what is the credit position of the counterparty to the in-the-money deal ?, They are likely to be suffering financial pressures commensurate with the negative value the contract represents for them; but the original company cannot be indifferent to this counterparty’s ability to perform.

Assuming the credit situation is not (yet) at crisis-point, it would be wrong for the first party simply to be satisfied with the security of the position and do nothing. The potentially damaging, indeed possibly deteriorating, situation the counterparty faces is likely to generate commercial forces that will bring the parties eventually to the negotiating table. Wait too long, and a crisis may indeed develop. By contrast, a timely pro-active approach, firstly to analysis and then to creative commercial engagement, can pay very big dividends.

In the next article in this series we consider the nature of typical renegotiation dynamics and set out a framework for systematic development of the commercial potential.

Nick Perry is a Senior Associate of Timera Energy. He has worked on large structured energy transactions for over 30 years, both as a principal and a consultant.