This is the second in a series of articles on commercial negotiation of long term energy contracts, written by Nick Perry.

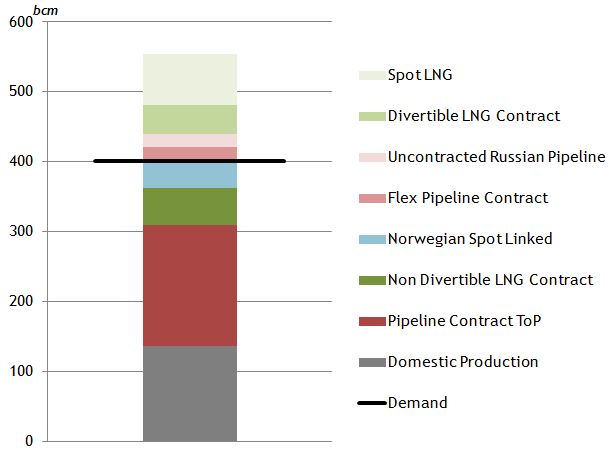

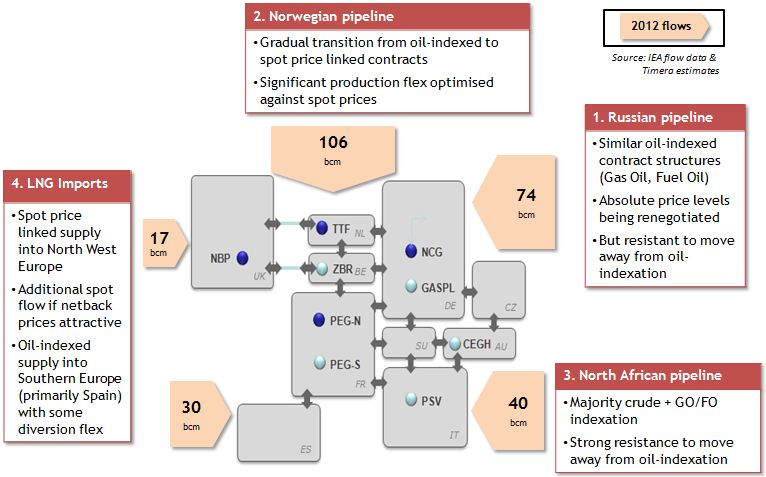

European gas contract re-opener negotiations are re-shaping the pricing and flexibility of gas flows into Europe. Re-opener discounted tranches of Russian gas are having a growing influence in setting marginal hub prices. Greater portfolio supply flexibility is being facilitated by the negotiation of spot indexation, take or pay volume reductions and LNG delivery flexibility. Most of these renegotiations are being triggered by concerns around contract price level. But as parties come to the negotiating table there is a lot more in play.

In the first article of this series we noted that long-term energy transactions, like other forward contracts, generally have a very small mark-to-market (MTM) value for both parties when the deal is first done. However, over time the contract can increase in MTM value very significantly for one side – and decline in value correspondingly for the other. We now consider how this potentially damaging commercial tension can be harnessed constructively to benefit both parties.

Getting to the re-negotiation table

Genuine commercially-motivated re-negotiations will typically occur when both the buyer and seller agree that ‘something has to change’. This may be even though the parties have very different views as to what this change should be before they get to the table. Clearly, for at least one party an extreme adverse MTM value-shift can be one such reason for seeking changes.

European energy contract re-negotiations are usually initiated via one of two routes, depending on the legal jurisdiction under which the contract was signed:

- Contracts entered into under a Civil Code approach (found in most European, South American and non-English-speaking Asian countries), typically contain re-opener clauses that specify the conditions under which contract counterparties should come together to resolve a dispute.

- Contracts entered into in a Common Law context (as found in most of the English-speaking world), typically do not have a formal contractual trigger for renegotiation, meaning that it is usually commercial incentives that bring parties to the table.

For those interested, a further analysis of Common Law and Civil Code context is provided in the breakout section below. Otherwise, we move straight on to the commercial considerations in contract negotiation.

Further analysis: A Layman’s Guide to Common Law vs Civil Code context

In a Civil Code context, conditions of extreme market movements or any other cause of material change in contract MTM value make it almost inevitable that re-negotiation will occur. By contrast, the Common Law legal tradition is for contracting parties to make changes to contracts only through bilateral (re-)negotiation, coming together for this purpose on a voluntary, ‘willing buyer, willing seller’ basis.

[Read more]

Under the Civil Code approach (found in most European, South American and non-English-speaking Asian countries) there can be circumstances in which a commercial court could intervene to impose a change in price and other contract terms: and one or other contract party could unilaterally approach the court for such a ruling – usually when they were in financial distress arising from the terms of the contract. In advance of such a situation (i.e. when the contract is first being negotiated) parties are naturally reluctant to leave their future commercial fate for a general commercial court to decide, and would prefer expert arbitration.

To avoid the courtroom, LTCs subject to Civil Code jurisdiction therefore generally contain ‘re-opener’ clauses which dictate conditions under which one or other party can demand that the contract be submitted for expert determination, which both parties agree in advance they will accept. These clauses will typically state a time-interval (e.g. 3 years) and a ‘threshold of pain’ (e.g. extent of change in market conditions) which must be met in order for one party to be able to call for arbitration unilaterally. It is usual for re-opener clauses also to require negotiations to be conducted in good faith prior to the suffering party invoking arbitration.

Common Law parties sometimes agree that foreseeable contractual disputes on minor matters are to be settled by arbitration; but it is very rare that they would allow arbitration to change something as fundamental as contract price, however extreme the market circumstances.

Likewise, under Common Law, the courts are generally unwilling to impose a change in contract price or other significant terms, even if the contract has become materially out-of-the-money for one party. So any re-negotiation will take place only because both parties feel they have something to gain.

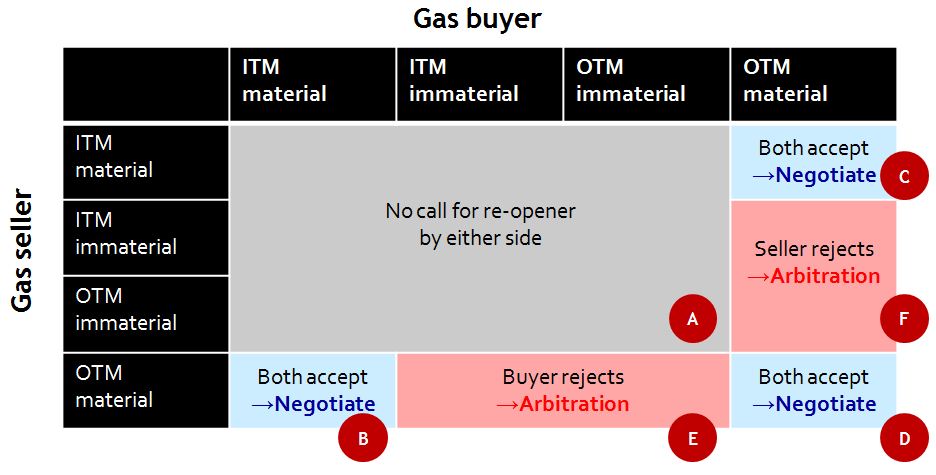

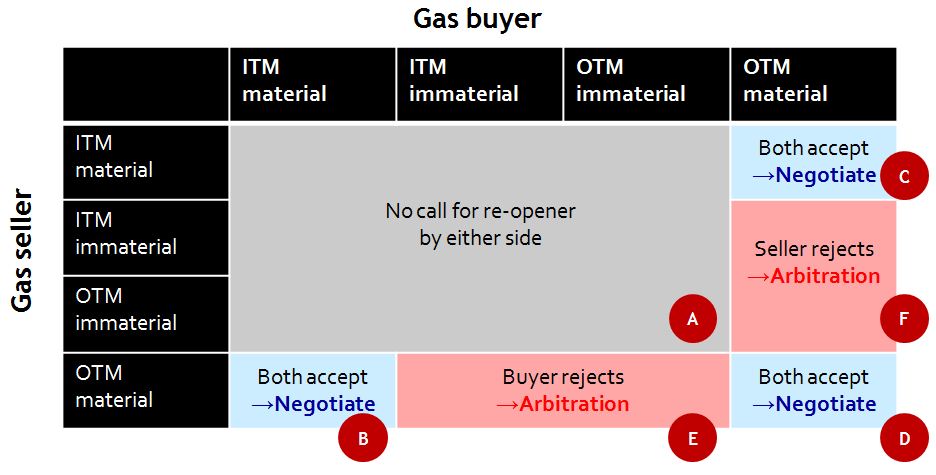

Negotiation – Civil Code context: contract renegotiations follow a formal re-opener process. The potential paths through the re-negotiation of a long term gas supply contract are illustrated in Diagram 1.

Diagram 1: European long term gas contract re-negotiation map

In the diagram we take the extent to which the contract has become out-of-the-money (OTM), either ‘material’ or ‘immaterial’, as a proxy for the degree of pain being suffered by a contract party. Material represents MTM stress above the contractually defined ‘pain threshold’ to trigger a re-opener. If the buyer assesses the contract is OTM for itself we assume it will assess it as being correspondingly in-the-money (ITM) for the seller. It is worth noting however, that it will not always be that the buyer and seller agree in their assessments either of their own position or their counterparty’s.

There are broadly 3 potential situations that can arise:

1. No re-opener

If both the buyer and seller independently assess that the contract is (i) ITM for themselves, or (ii) OTM but only to an immaterial extent (i.e. below the ‘pain threshold’). Then they will not convene to re-negotiate (the grey area marked A in the diagram).

2. Negotiation

If the buyer and seller both agree that one of their positions is OTM to a material extent, then they will meet to renegotiate (areas B and C). This has been illustrated by the more proactive approach Statoil and Gas Terra have taken to renegotiating some of their ITM contracts with European suppliers (area C).

Interestingly, if both parties simultaneously consider the contract is OTM for themselves (and they might both be right!), they will also meet to renegotiate (area D) even though they may be seeing things differently. This can be the most fruitful circumstances for a win-win outcome!

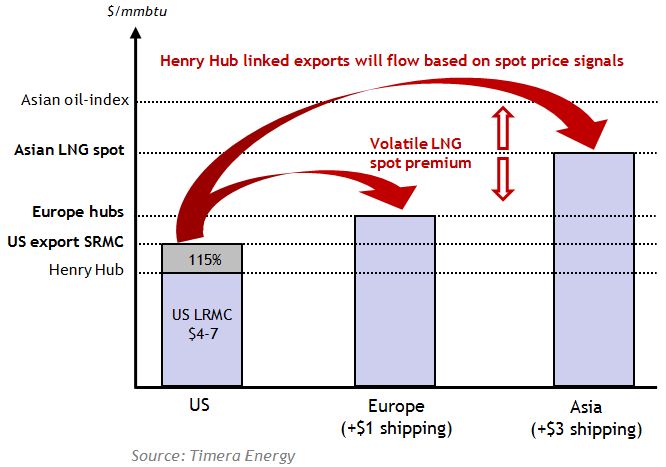

An example of this is an oil-indexed European LNG supply contract with a fixed destination clause, which is OTM vs European hub prices for the buyer and OTM vs Asian LNG prices for the seller. Both parties win from cancelling the contract, or negotiating diversion rights such that upside is shared between the buyer and seller.

Of course, nothing guarantees that re-negotiations will succeed, and ultimately the case may go to arbitration (or the courts).

3. Arbitration

Arbitration tends to result when the buyer and seller disagree on the size/impact of the change in contract value. For example, if the seller is of the view that the contract is OTM for itself and the buyer rejects this assessment, the seller will invoke arbitration (area E): or vice versa for the buyer (area F). A prominent example of this is the recent arbitration cases between Gazprom and large European gas suppliers, where there has been a fundamental disagreement over the role European hub prices play in determining the long term value of gas.

Negotiation – Common Law context, there are typically no formal contractual drivers for the re-negotiation process, or recourse to arbitration or the commercial courts. What happens commercially will then be a function of the attitudes of the parties. If the ITM party is reluctant to engage, without a back-stop of arbitration sometimes the only ‘threat’ available is for the OTM party to hint at inability to perform the contract. In extreme circumstances some distressed parties have been known to default deliberately in order to trigger negotiations. There were several cases of this happening in the period 1995-98 in the UK, when the gas price collapsed and many contracts became significantly OTM. Needless to say, this often degenerates into litigation, and represents a failure of sound commercial practice.

It must always be a principle of good business that parties should at least meet to explore each others’ positions. Regrettably, in both Civil Code and Common Law contexts the ITM party often enters discussions with the time-worm attitude: what’s mine is mine, and what’s yours is open for discussion.

Identifying opportunities for win-win

When an OTM party comes to the table it will generally be self-evident as to what changes ideally they would like: at its most basic, a distressed seller will ask for a higher price and a buyer will want a lower. As we noted in Part 1, the counterparty must certainly have uppermost in mind a clear perception of what is at stake, not least when the LTC represents a hedge.

In consequence it can be all too easy to see the matter as a straight win-lose, zero-sum game: the buyer wants a lower price – how can that be other than at the direct expense of the seller? Unless there is a genuine prospect of the buyer’s bankruptcy (which would completely nullify the seller’s hedge), can the buyer’s appeal for a lower price be other than a charitable request (perhaps based on the business relationship)?

Nine times out of ten, for the seller to approach the situation from this limited perspective is culpably to ignore the scope for creative outcomes.

One of the most striking aspects of energy LTCs is how complex they are – inevitably so, as they must cover the wide range of contingencies which energy companies face. To contract administrators, complexity can be a nightmare! To the creative negotiator, however, complexity is a rich source of commercial possibilities.

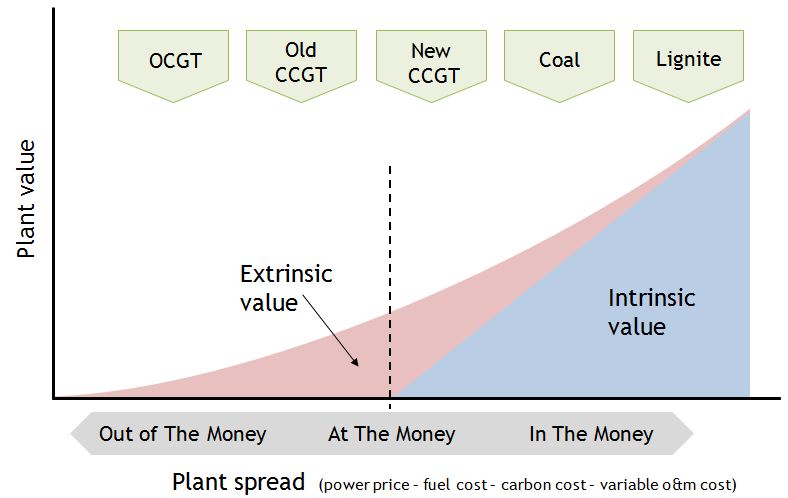

At very least, LTCs will frequently contain terms such as price-indexation formulae and flexibility provisions (swing, take-or-pay, carry-forward etc). These represent multiple dimensions, all of which can be analysed for the value that lies in them. And whereas the buyer and seller will typically have the same view of the value of one unit of price, they may have quite different assessments of the value of, say, an incremental 10% of swing, or a switch from oil indexation to spot-gas indexation in the pricing formula. This has been illustrated in the recent renegotiated outcomes of many of Gazprom, Statoil and Gas Terra’s contracts with suppliers.

Thus, price may to some degree readily be traded for movement in one of the other basic dimensions of value, for example the price decrease may be bought with an increase in flexibility. Here it is very usual – and commercially helpful – for valuation of flexibility / optionality to vary widely between different players in the same market. This is often the source of great opportunity for a win-win negotiated outcome.

Getting creative

But this is only the start of the creative thought-process. At its most general we can assert that over time, even an LTC that seemed perfect to both counterparties when first negotiated will start to become less satisfactory in many details. Given the complexity and sheer length of tenor of energy LTCs, and the significant changes that take place in energy markets, this is inevitable. The buyer will have his list of various changes he would ideally like to make, ranging across the whole contract, and the seller will have his own – likely to be different in many respects, which is exactly what gives rise to potential for fruitful trade-offs.

Therefore, both parties, including the ITM party, should be approaching the table with a prioritised – and carefully evaluated – wish-list. The list of possibilities is endless, including entirely new contract terms, and the number of dimensions in play goes far beyond price and flexibility. Everything has a price, and constructive win-win trades should be possible between open-minded and commercially-creative counterparties. There should always be a commercial pretext for constructive re-negotiation.

Viewed in this way, when an LTC becomes materially OTM it is seen as a catalyst for all-round win-win contractual enhancement, in which the suffering counterparty can trade for some degree of relief against its main source of pain. This is the correct mind-set for companies approaching a re-negotiation.

But this is not the end of the story, and in the final article of this series we consider an even more wide-ranging perspective on energy contract re-negotiation.