This week’s article is written by Howard Rogers, a Senior Advisor with Timera Energy and Director of Natural Gas Research at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

The European transition to hub-based pricing is now well underway. This raises the question as to whether Asian LNG markets will inevitably evolve away from their historic linkage to oil prices in long-term LNG contracts. There is a level of discontent among Asian buyers that is supportive of a transition to an alternative pricing mechanism. But it will likely take a bigger catalyst to pave the way towards Asian hub-based pricing.

Hub evolution in Europe

First let’s look at the three factors which conspired to change the European gas pricing landscape:

- Pro-competition policy and legislation enabled third-party access to infrastructure, end-consumer supplier choice and the erosion of incumbent territorial domination. This created the framework in which traded hubs could develop.

- From 2009 a combination of plentiful new supply (LNG which the US did not require) at a time of reduced demand (because of the financial crisis and recession) created a significant spread between hub prices and oil indexed pipeline gas prices.

- The subsequent unsustainable financial exposure of the midstream utilities which required them to seek arbitration and negotiated price reductions in their long-term gas contracts. Now in NW Europe, long term contract prices are either explicitly hub indexed or are ‘adjusted’ to be equal to or very close to hub prices.

In the Asian LNG market there is the potential for the second and third of these factors to transpire, but a large question mark against the first.

An Asian solution?

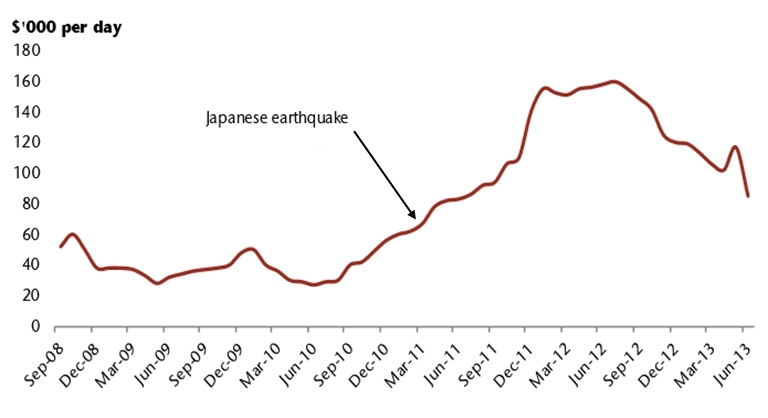

High Asian LNG prices (as a consequence of $100/bbl plus crude) have resulted in a chorus of complaints from Asian LNG buyers. But there is no consensus as to whether the problem is one of ‘price level’ or ‘price formation’. Continually adjusting price levels (by changing price formula variables) is one solution, but becomes somewhat futile if the underlying price formation mechanism no longer has any market logic.

If the problem is one of ‘price formation’ there are a number of alternative options. The first is to re-assess the fuel mix in which gas competes, and derive a suitable multi-fuel price index. The main problem here is the need to re-calibrate the index frequently as markets evolve and the fuel mix changes. This approach also presumes the continuation of a structure in which oligopoly sellers interact with midstream incumbents. The second approach is to use an existing spot LNG index such as the JKM. At present this is quite volatile, possibly reflecting relatively low coverage of total Asian spot LNG trades. Pricing based on Henry Hub currently has its attractions at current US – Asian price spreads, but may become more questionable if the oil price falls and US shale production, in time, disappoints expectations.

The last option in the list is an Asian trading hub price. While this is probably the preferred option, achieving it (as is often the case) will require several challenges to be overcome. More on this later. As was the case in continental Europe, market fundamentals play an important role in such pricing transitions. So rather than discuss these possible changes in a ‘theoretical vacuum’ let’s look ahead over the next ten years. Although subject to many uncertainties, there is a good possibility that the period 2018 to 2023 could be one of plentiful LNG supply, with consequences for major players but also offering favourable conditions for an Asian LNG hub to develop.

Could new LNG supply be the catalyst?

We have the co-incidence of significant US LNG export volumes coming at a time when Australia and other suppliers will also be bringing new projects on stream. In part this will be aided by aggregator/portfolio players who are contracting US volumes with no fixed corresponding end-user contract. The big uncertainties are:

a) Continuation of the robust US shale gas production performance; and

b) Chinese future demand for gas and LNG.

A key dynamic will be how Russia (supplying 25% of Europe’s gas) will respond to a potential overspill of LNG into Europe. This could be in the form of a price war which would lower hub prices in Europe, the US and Asian spot prices, further increasing the incentive to move to an Asian LNG hub index.

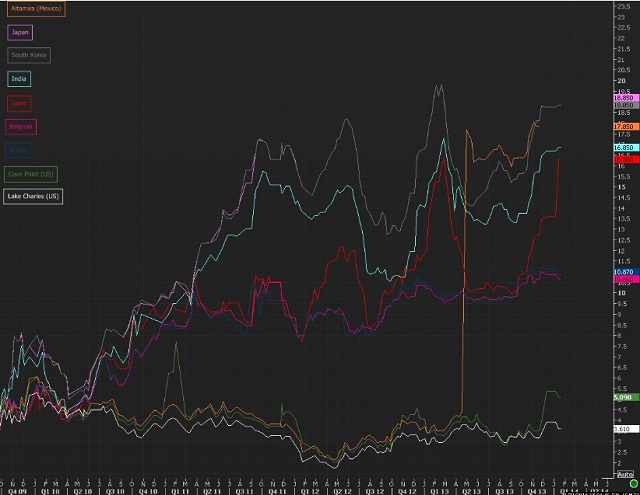

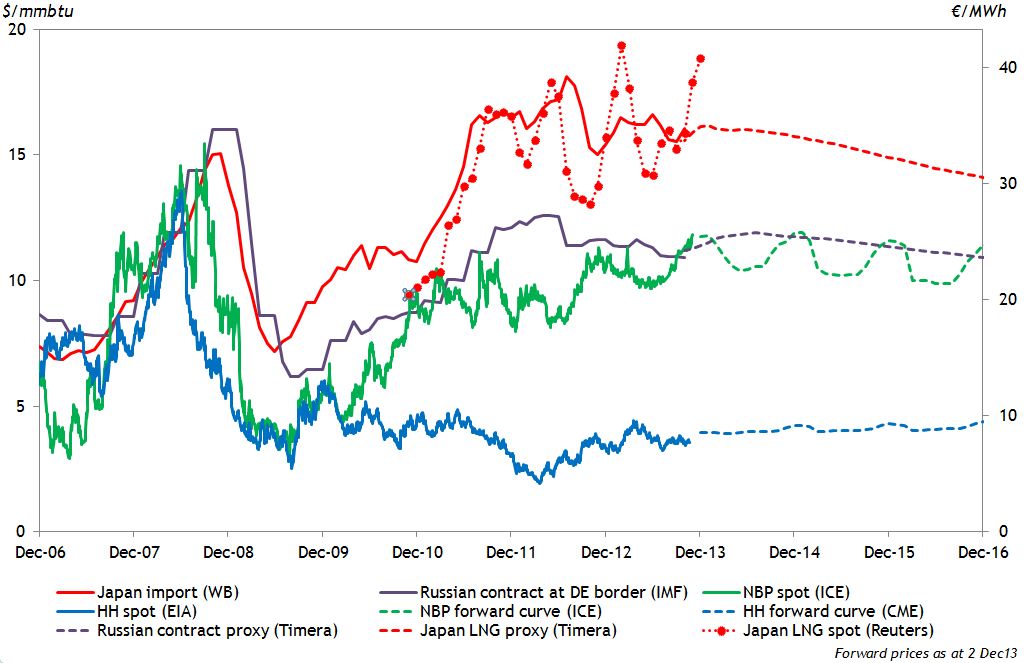

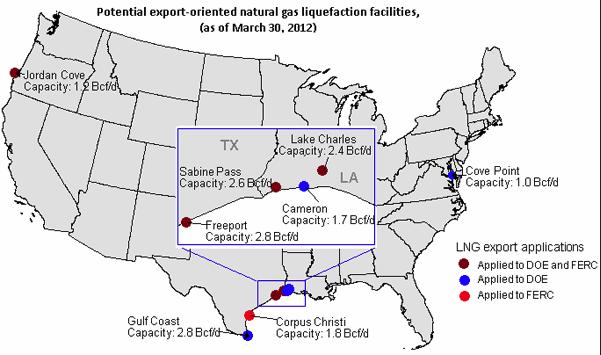

The major change over the last 12 months or so has been the scale of potential US LNG export projects moving through the approval process. At a more sustainable Henry Hub price of $6/mmbtu it is feasible that these ‘re-gas re-configuration’ projects could remunerate incremental investment costs at European hub prices of around $10.50/mmbtu and Asian prices of around $12/mmbtu. Some 85 bcma of LNG has received non-FTA approval from trains in six projects which have offtake agreements (or HOA’s) for 112 bcma.

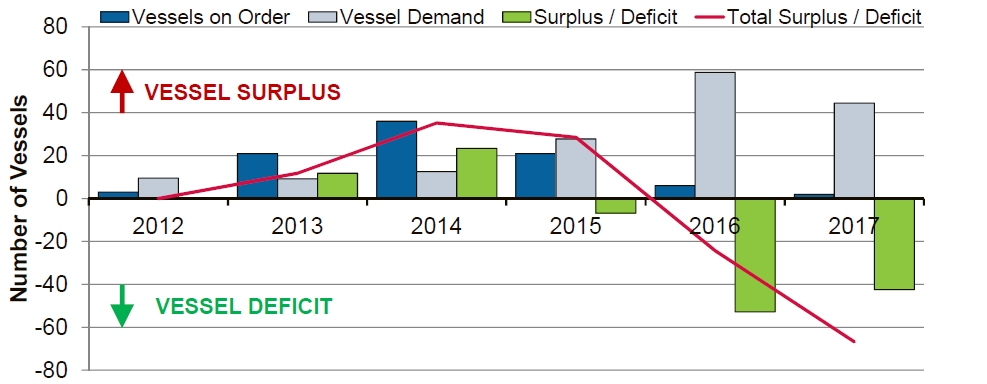

Chart 1: US LNG Export Projects: Timing and Off-taker Type

Sources: Company & Media Reports, Author’s Assumptions

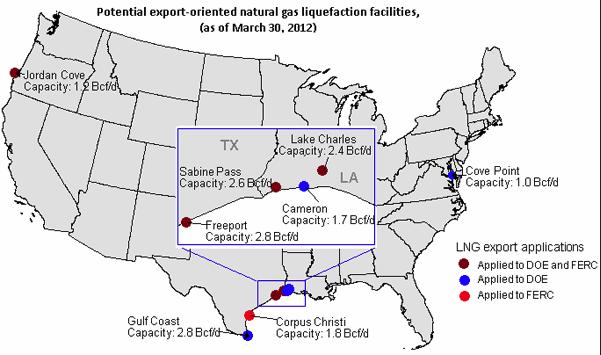

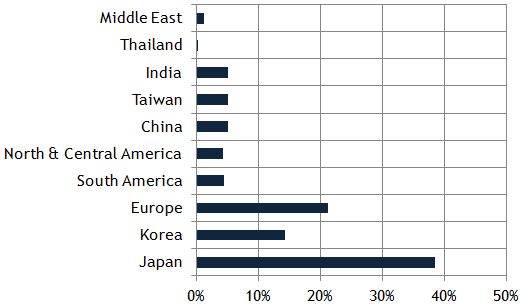

A breakdown of Asian LNG demand vs supply

The graph above shows that while Japan, South Korea and India have been active, the majority of these volumes have been secured by aggregators & portfolio players. While Sabine Pass is likely to start up at end 2015/early 2016, capacity from these projects starts in earnest post 2018.

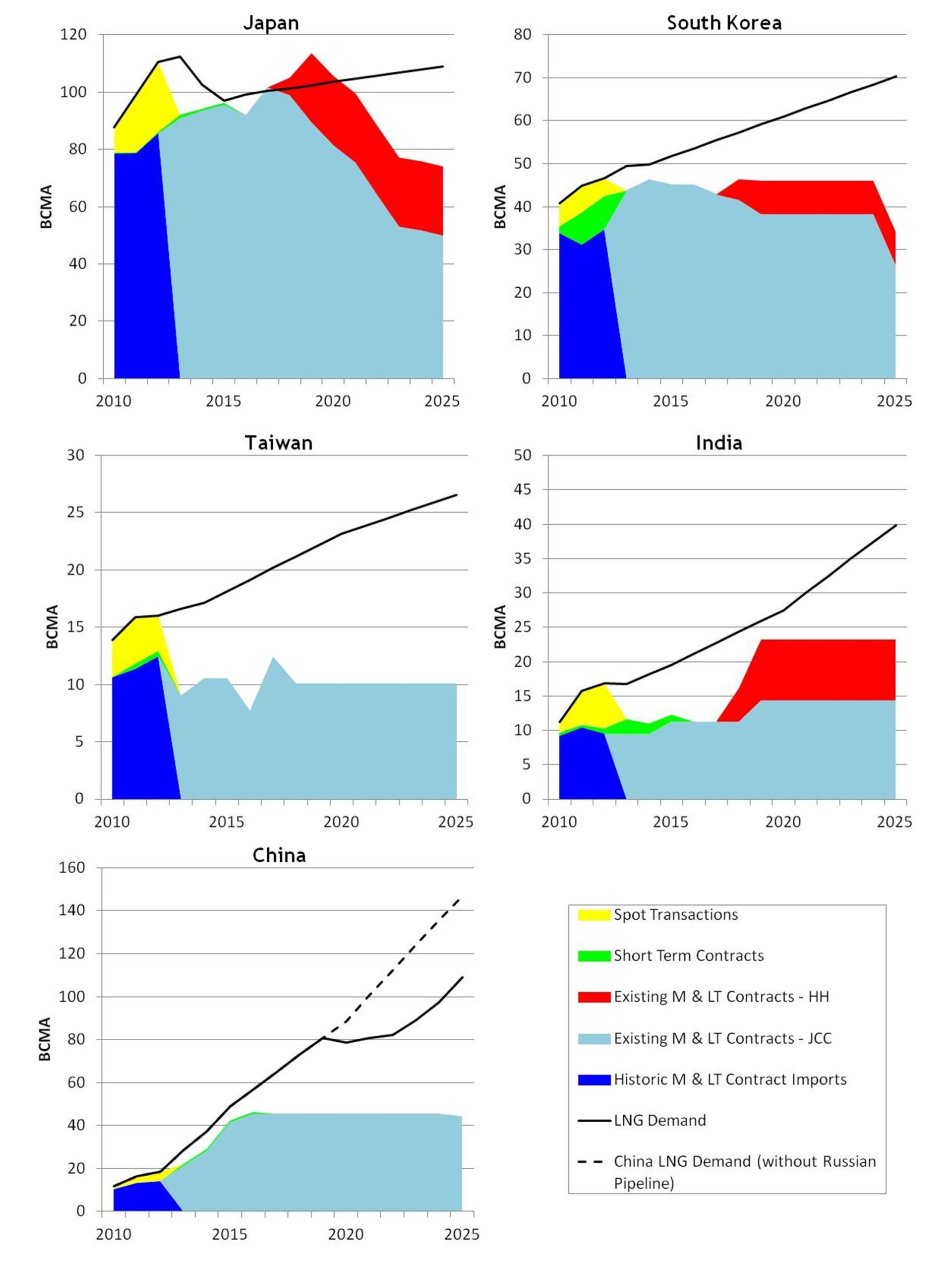

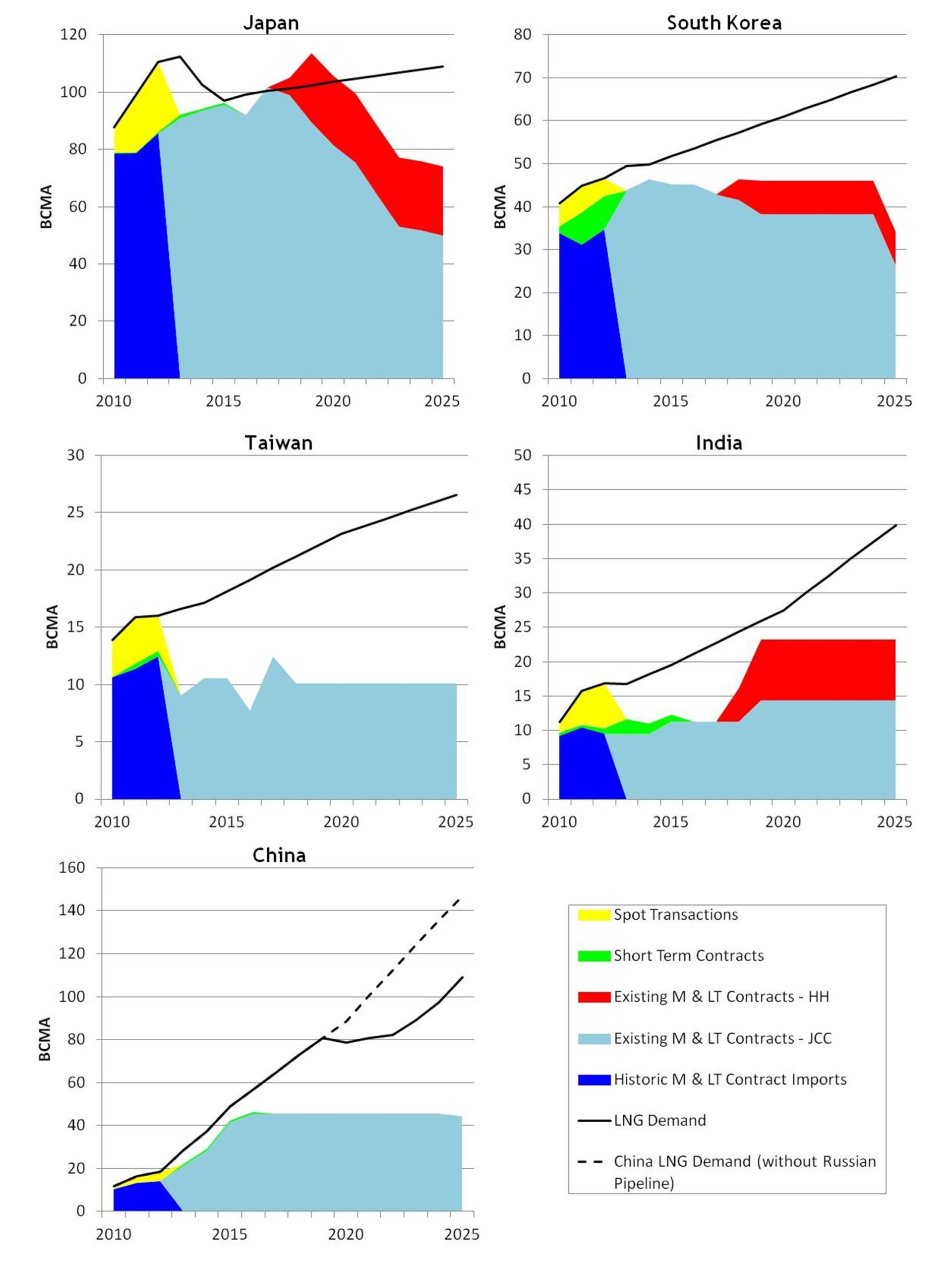

Chart 2: Asian LNG Importers – LNG Contract & Spot Demographics 2010 – 2025

Source: GIIGNL, Author’s assumptions, D Ledesma OIES.

The above figure shows the illustrative LNG requirements of the 5 main Asian LNG importers. LNG demand is the black line. Long Term contract supplies are in blue (dark blue historic, light blue future supply from existing contracts). Green represents supplies from existing short term (less than 4 year) contracts and yellow historic spot LNG supply. The red represents volumes of US LNG from offtake agreements or Heads of Agreement signed by Asian buyers. Note that these graphs exclude: future Spot LNG volumes from existing and new projects, US volumes secured by aggregators/portfolio players and long term contracts from projects which have net yet achieved FID.

In the case of Japan, once nuclear power plants have re-started, the existing portfolio of JCC contracts fulfils demand until 2018/2019. The US volumes continue to satisfy demand until 2020/2021. Unless Japan is able to materially renegotiate the terms of its existing LNG contract portfolio away from a JCC basis, it will not be able to change the price formation basis of its LNG imports until the end of this decade. South Korea is in a similar position but has more room to introduce spot volumes and towards the end of the decade has flexibility to insist on a move away from JCC in order to change its portfolio price formation balance.

India’s future LNG requirements are uncertain for many reasons but GAIL has been active in securing US volumes. Taiwan being a small market will probably continue to rely on spot LNG in the main. China appears to have a requirement for supplies in addition to its current contracted portfolio from 2016 onwards. It has not signed any agreements for US volumes but is active in both Canadian and East African ventures. These however are unlikely to be onstream until 2020.

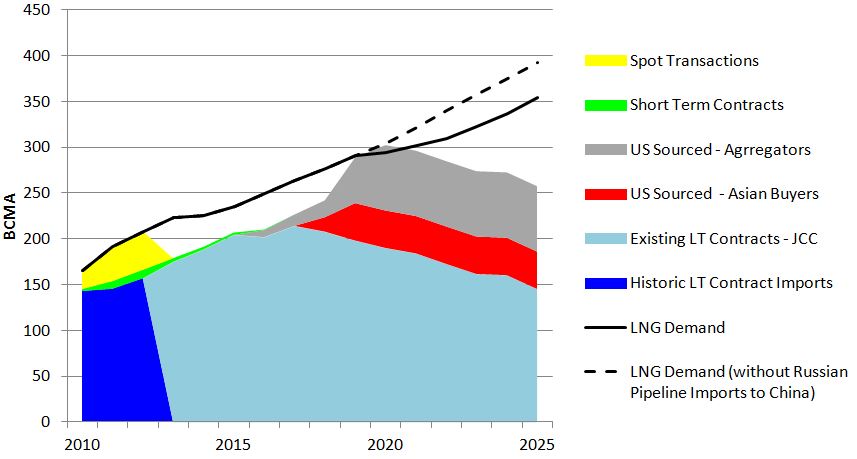

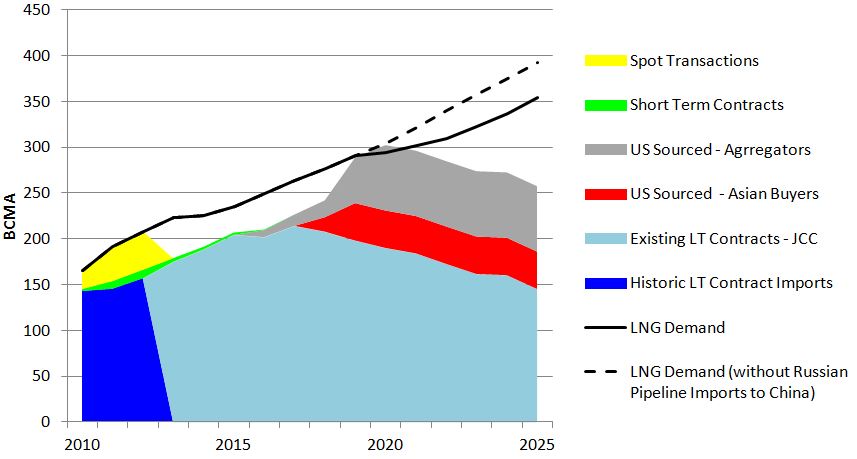

In the next figure we look at the aggregate position and add in the US volumes signed up by the ‘Aggregators/ portfolio players’ in grey.

Chart 3: Asian Future LNG – Contract, Spot and Price Formation

Source: GIIGNL, Author’s Assumptions

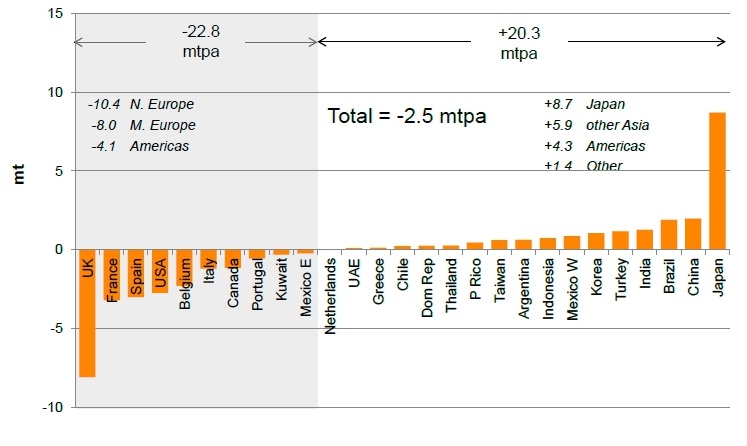

This suggests that, on the basis of the assumptions behind these projections, if all US volumes are directed to the Asian LNG market, in the 2018 – 2023 period there is little room available for spot LNG volumes from existing and new projects/suppliers and long term contracts from projects which have net yet achieved FID. This is indicative of a potential period of oversupply during which Europe could receive an ‘overspill’ of excess LNG supply as it did during 2010 and 2011. If these conditions transpire, they could be a key catalyst for a shift to Asian hub-based pricing.

The path to an Asian LNG hub

We now return to the challenges of creating a hub in Asia. Unlike North America and Europe, Asia lacks a major liberalised national pipeline gas market. Even if one or more existed, geography would prevent an integrated regional market being created through pipeline interconnections. As such, there is little prospect of a major regional traded gas hub, initially developed on the basis of pipeline gas supply, providing the platform on which LNG can be traded. For Asia therefore, it makes more sense to anticipate a hub developing purely on the basis of LNG trading.

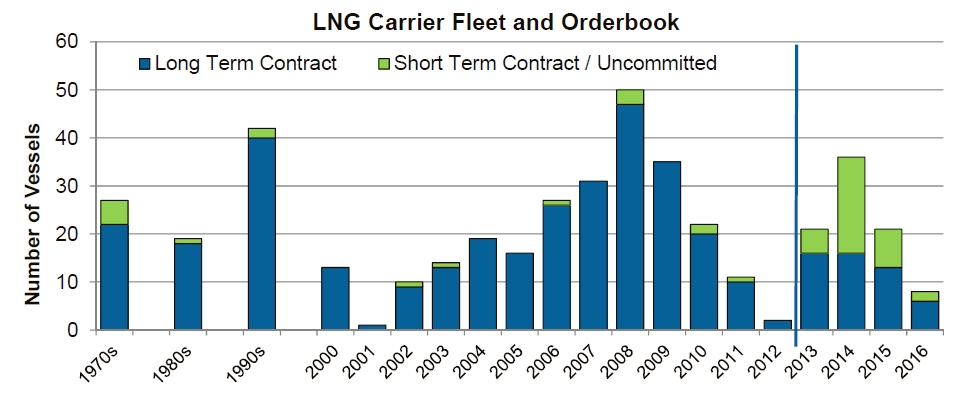

Singapore has made a start during 2013. However even if all Asia’s spot LNG (40 bcma in 2012) flowed through a hub, that would only represent about 1.5 cargoes a day. Given the distance between Singapore and the major Asian LNG markets it is probably that part-cargo trading is difficult on cost grounds. Liquidity could improve if for example a substantial portion of the future grey aggregator volumes in the previous figure were to be sold on the Singapore hub. What is more likely to succeed longer term is the establishment of hubs at say Tokyo and Shanghai, where part-cargoes could be traded. This assumes however that buyers other than the midstream utilities (such as large industrials) are able to purchase part cargoes through enforced third party access at regas terminals. Whether the willingness exists at a national policy level to instigate such changes is as yet unclear.

At present, based on research and thoughts to date, the following three scenarios for the Asian LNG Market are offered:

Scenario 1 – Contractual Impasse. This is where we have been for the past year or so and are likely to remain for a year or so more. Buyers continue to complain about JCC pricing but no changes can be agreed with sellers on existing contracts. Buyers refuse to sign new long term contracts at prices linked to crude oil, producers refuse to sign on any other basis and so no new contracts are signed (apart for those where the supply is from the US). US export growth increases spot trade but the Asian LNG sector overall stagnates.

Scenario 2 – Smooth Contractual Transition Scenario in which new long term contracts begin to be signed on an alternative basis to JCC with price review clauses anticipating a future Asian LNG hub. There are challenges to existing contracts but re-negotiations result in adjustments which are tolerable to buyers and sellers. Despite ongoing financial pain, Japanese buyers manage to ‘hang on’ until existing contract portfolios decline. Spot trading increases and by the 2020s larger and more liquid hubs emerge in Tokyo and Shanghai and new long term contracts are signed on the basis of these prices. This scenario has most chance of transpiring at oil prices below $100.

Scenario 3 – the Contractual Train Wreck Scenario. Here Asian buyers’ losses (particularly those in Japan) become so serious that they demand re-negotiations on existing contracts. These are resisted by suppliers who continue to demand JCC linked pricing. Litigation is started with unpredictable results and large financial sums at stake. No new long term contracts are signed during this period (apart from those based on US supply) but spot trading continues to increase and eventually liquid hubs emerge in Tokyo and Shanghai and new contracts are signed on the basis of hub price indices. This scenario is more likely at oil prices above $100/bbl.

Given the changes in importing market structure since the 1970’s, it is extremely difficult to make the case that JCC is still a rational basis for pricing Asian LNG. It has created huge financial problems for Japanese buyers and threatens longer term competitiveness. While US exports contracted on a Henry Hub plus costs basis appear more attractive at present, this may not be the best reflection of global LNG supply and Asian market fundamentals in the longer term. Over time, one or more Asian LNG trading hubs would establish more appropriate prices. But there are significant challenges to achieving the necessary liquidity, requiring difficult choices and resolve on the part of buyers and policymakers. Transitioning to this more enduring price formation basis while addressing the challenges of existing Long Term JCC contract portfolios could be a long and bumpy ride!

A more in depth look at the issues discussed in this article can be found in the OIES paper entitled Challenges to JCC Pricing in Asian LNG Markets penned by Howard Rogers and Jonathan Stern.