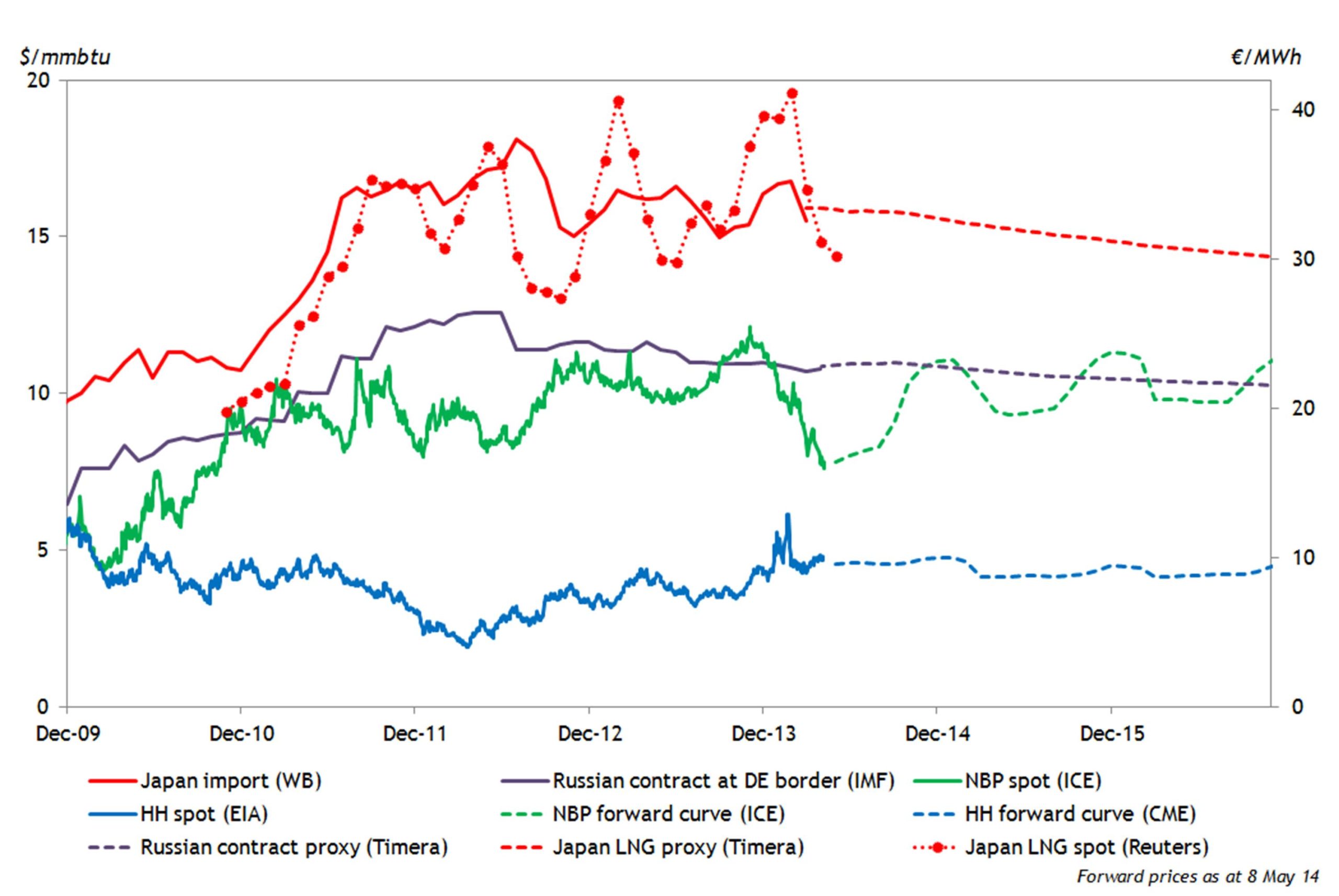

The Fukushima disaster in March 2011 precipitated a shift in global gas market balance. A period of market tightness followed, driven by robust Asian demand and constrained supply growth. This post-Fukushima period has been characterised by global gas price divergence as Asian and South American buyers have had to pay a premium to attract LNG supply from Europe.

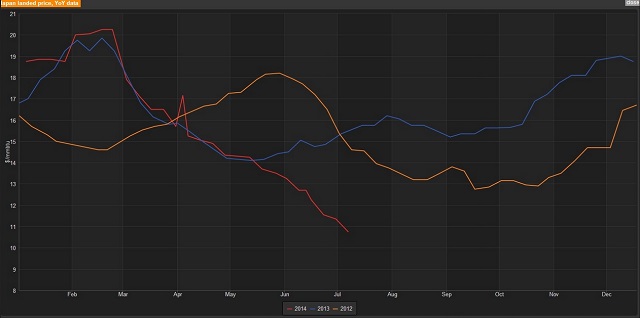

But the last six months has seen a seismic shift in global gas pricing. Step back to the start of 2014. As the year commenced, Asian spot LNG prices were near all time highs around 20 $/mmbtu. Buyers were scrambling to cover both short and longer term portfolio exposures. There was a strong market consensus that this period of tightness would continue at least until the second half of this decade, when large volumes of new supply are due, if not into next decade. That market consensus has been shattered by the slump in global gas prices across Q2 and Q3 of this year.

Risk of a shift in global gas balance

The risk of a shift from post-Fukushima market tightness towards a period of global oversupply has been a key theme of this blog. For example:

- In early May 14 we set out in detail the case for a shift to global oversupply and the associated commercial implications.

- In Feb 14 we showed a breakdown of the key elements of global supply & demand and how these pointed to the risk of a period of oversupply.

- In Dec 13 we highlighted a list of potential risks entering 2014, at the top of which was a pronounced decline in Asian spot LNG prices and European hub prices.

- In Oct 13 we highlighted the importance of new US export supply in driving global price convergence & reducing LNG portfolio flexibility value.

- In Jul 12 we described the risk of a more structural re-convergence in global gas prices.

We do not claim to have forecast the events of the last few months. But for the last two years we have questioned the strength of market consensus around continuing global gas market tightness. Price risk in our view has been firmly focused on the downside given bullish expectations, large & chunky volumes of committed new supply and uncertainty around the evolution of demand.

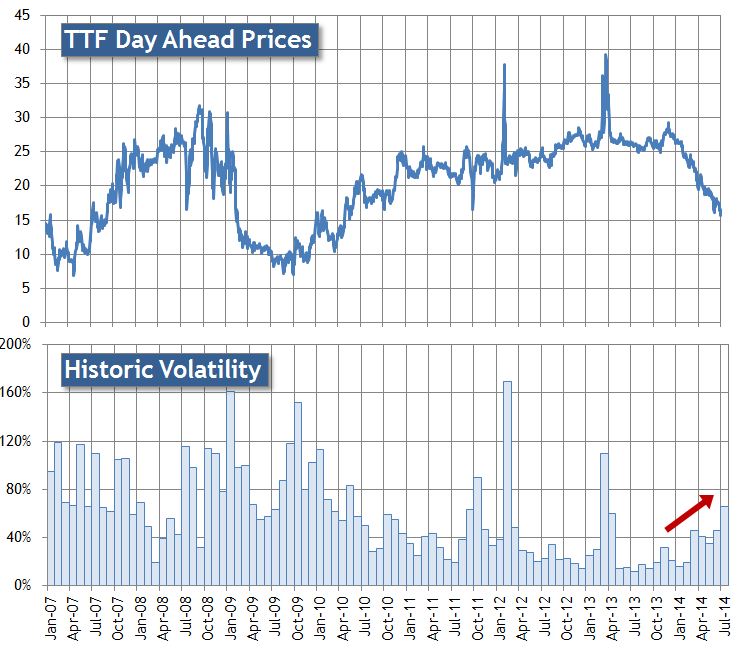

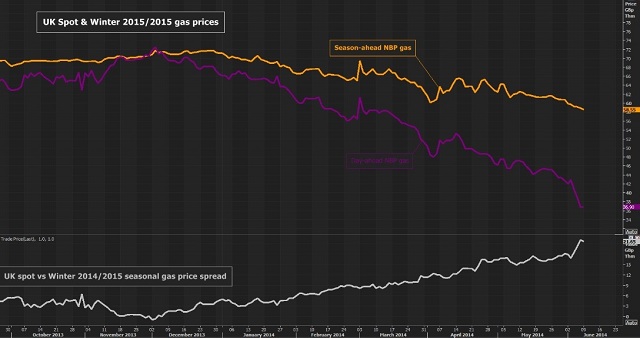

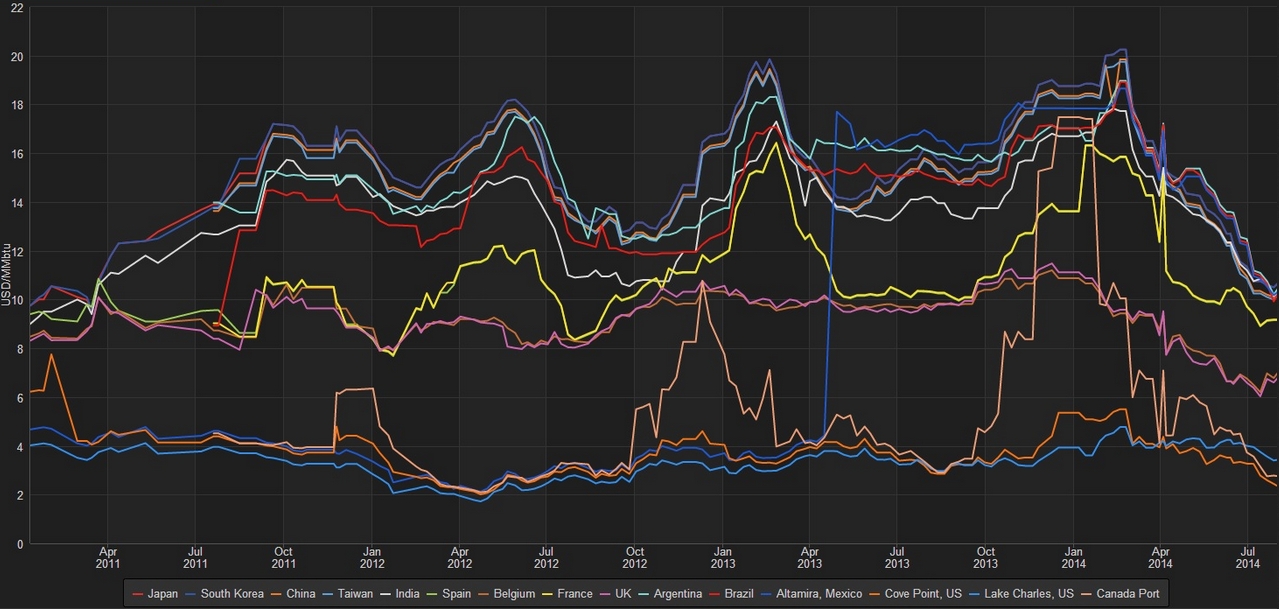

However the pace and global nature of the recent decline in gas prices has been alarming. This is well illustrated in Chart 1 which shows the evolution of LNG spot price benchmarks covering the period since the Fukushima disaster.

Chart 1: Global LNG spot price evolution (2011-14) click on the chart for a blow up view

Source: Reuters (using Waterborne spot LNG data)

The rapid divergence of Asian prices after the Fukushima disaster in Mar 2011 can be seen to the left of the chart. Asian price divergence has remained a structural characteristic of the global market across the proceeding three years, although there have been seasonal dips in Asian spot prices over the summers of 2012 and 2013.

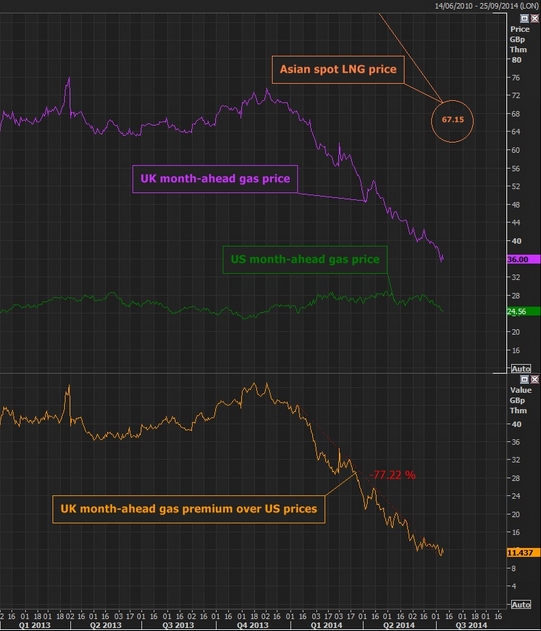

But the period from Apr 2014 marks a shift to a much sharper decline in Asian spot prices towards 10 $/mmbtu. As this has closed out the value from diverting European supply, LNG has flowed back into Europe driving down hub prices. US gas prices have also declined somewhat, although there has been a pronounced convergence in cross Atlantic pricing as European prices have slumped. As things currently stand, the state of global price convergence is broadly similar to the period preceding the Fukushima disaster in early 2011.

It is easy to get caught up with market momentum and forget that the recent decline is partly seasonal in nature. Largely due to milder weather, European demand for the period October 2013 to April 2014 was 57 bcma lower than the corresponding period in 2012/2013. In Asia LNG demand (with the exception of China) appears to have flattened out on a 12 month rolling average basis. While it is widely claimed that this is a weather-induced effect, there is little evidence for this apart from in South Korea.

Prices are already stabilising from their summer lows and may make a meaningful recovery into the winter. For example recent forward pricing for LNG has exhibited quite a steep contango. Spot Asian cargoes for Aug/Sep delivery have recently been changing hands around 11 $/mmbtu, with cargoes for November delivery pricing above 13 $/mmbtu. While the extent of this winter recovery is uncertain, the price slump into the summer has already shaken market perceptions of the global supply & demand balance.

Some implications of the price shock

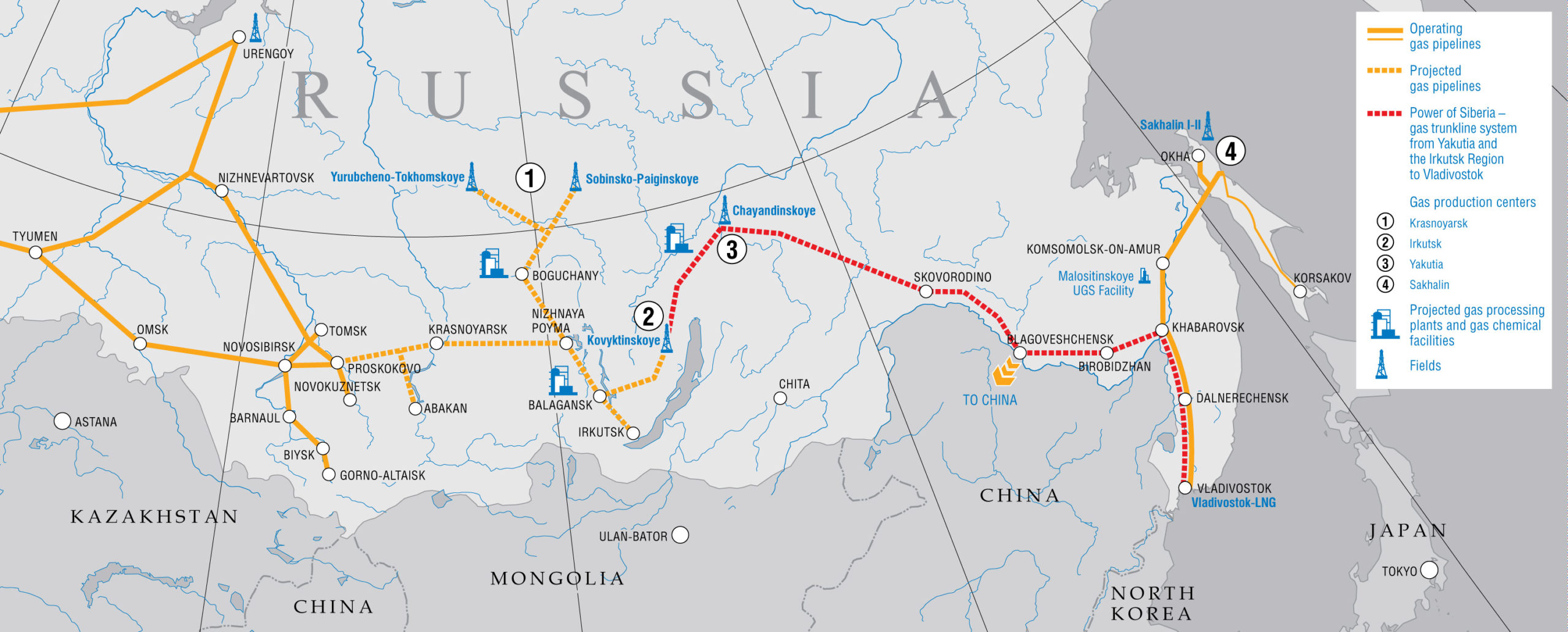

One of the more surprising characteristics of the 2014 decline in LNG prices is the fact that it has occurred in the absence of large volumes of new supply. While the Papua New Guinea LNG project commenced exports of spot cargoes in May this year contributing to pressure on Asian spot prices, its impact is relatively small scale in a global market context. The more substantial volumes of new Australian and US export supply still loom on the horizon as projects ramp up in earnest from 2015.

In Australia 85 bcma of new capacity (under construction) is set to come onstream by the end of 2018. In the US 40 bcma has achieved FID with 23 bcma of this under construction. It is the impact of this new supply that is spooking the market. Of key importance is how the recent price shock effects the development of new liquefaction projects and the negotiation of long term contracts.

The early evidence is pointing towards a sharp increase in reluctance from LNG buyers to commit to long term offtake contracts at price levels required by developers. Australian export projects are particularly vulnerable as they face the joint threats of weak spot prices, US export competition and a rising cost base. As an example Chevron’s Gorgon project is struggling to sell any additional long term contract cover as reported by Reuters last week. The $54b project which is due to start exporting in mid-2015 is only 65% contracted, well short of the comfort mark. In the absence of long term contract sales, Chevron is left with little choice but to sell volume into the Asian spot market and hope for a recovery in prices. The risk of delays and cancellation for projects which are at an earlier stage of development in both Australia and the US has increased significantly.

We will come back with more detailed analysis of the medium to longer term implications of this year’s price shock in subsequent articles.

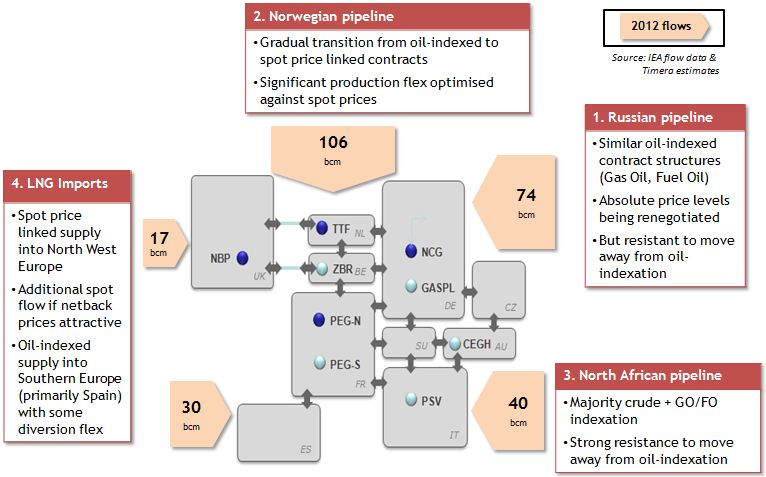

The way forward

A first observation on the current state of global pricing is that in many markets spot prices are significantly below long term oil-indexed contract price alternatives. This creates a strong incentive for suppliers to minimise their contract take and buy spot gas as a replacement if required. Coming into the winter, this is an important support mechanism both for Asian LNG spot prices and for European hub prices. As a practical example, one of the world’s largest LNG buyers Kogas has recently been negotiating to defer up to 10 contracted cargoes from this summer/autumn into the coming winter.

It is also worth noting that the LNG spot market still has relatively low levels of liquidity. This means a cargo overhang can have a pronounced impact on price as has happened over the summer. Illiquidity could also act to drive a sharper LNG spot price recovery over the coming winter if for example it is unseasonably cold or a major Russian supply disruption results in higher European demand for LNG.

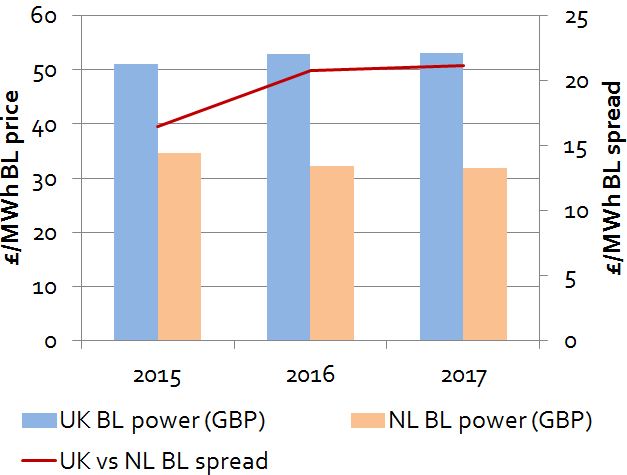

European hub prices are also showing signs of stabilisation as the seasonal focus shifts towards winter and the ongoing threat of Russian supply disruptions. European hub prices provide key support for global LNG spot prices, as liquid European hubs act as a market of last resort for surplus LNG cargoes. The extent of the recovery of both Asian spot LNG and European hub prices into the coming winter will be an important barometer for the state of the global supply and demand balance.

But regardless of how gas prices recover into the winter, we expect significant fallout from the recent price shock. There is a key risk that as new export projects ramp up in 2015 they contribute to an overhang in spot supply reinforcing global price convergence. While this poses a threat to the contracting and development of liquefaction projects, it is good news for LNG buyers. These are conditions that may support a strong pickup in LNG spot market liquidity and potentially the evolution of a more meaningful Asian hub price.

The global gas market has been defined by several distinct phases of evolution over the last decade: the commodity super cycle boom, the US shale and financial crisis driven bust and the post-Fukushima phase of market tightness. It is our view that the global market is now entering its next phase, potentially one of transition to a period of significant oversupply. This may have profound implications for the evolution of both gas and power markets over the next few years, a theme which we will continue to explore across the second half of this year.