Much industry analysis and discussion has been directed at European gas price formation, specifically the transition from oil indexation to hub pricing. But there has been less focus on the changing roles and risks of the key players. In this article we examine the drivers of European hub prices and attendant uncertainties and also the risks of key players compared to the pre-liberalisation era.

Revisiting the hub price framework

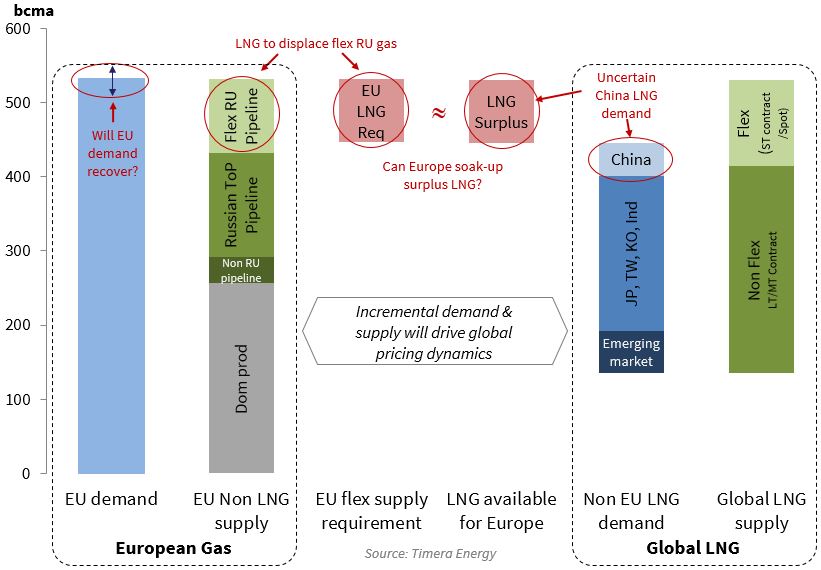

With hub prices eclipsing those of oil (product) indexation as the key wholesale reference price it is natural to ask the question ‘What are the determinants of European hub pricing?’ We have addressed this question previously in articles that set out and then applied a framework for the analysis of hub price behaviour. Two important conclusions from this framework approach are:

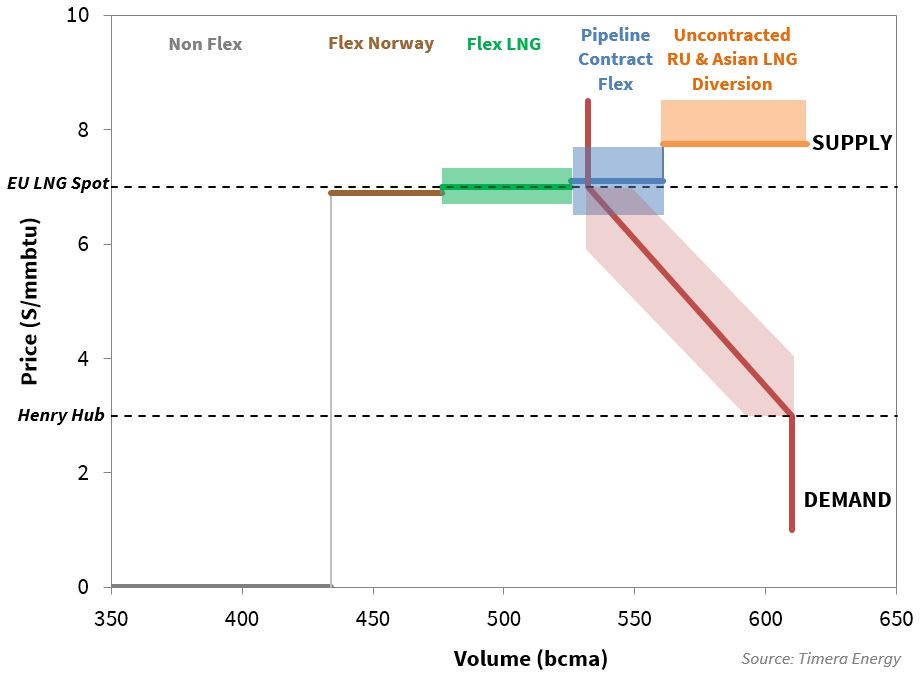

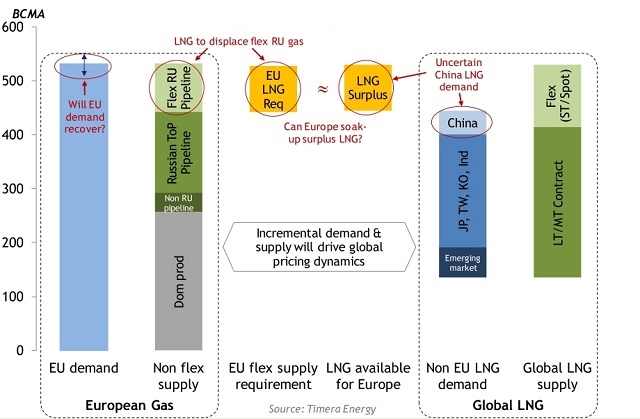

- If demand in Europe, which is linked by infrastructure to liquid hubs, is met at the margin by Russian pipeline gas above take-or-pay levels, then hub prices will gravitate towards the Russian oil-indexed contract price.

- If, however, demand is depressed and/or supplies of flexible LNG represent the marginal supply tranche for ‘liquid’ Europe, then prices fall below Russian oil-indexed contract prices. The exact hub price level depends on supply and demand dynamics and market sentiment, but important price support exists at levels where gas displaces coal in the power generation sector.

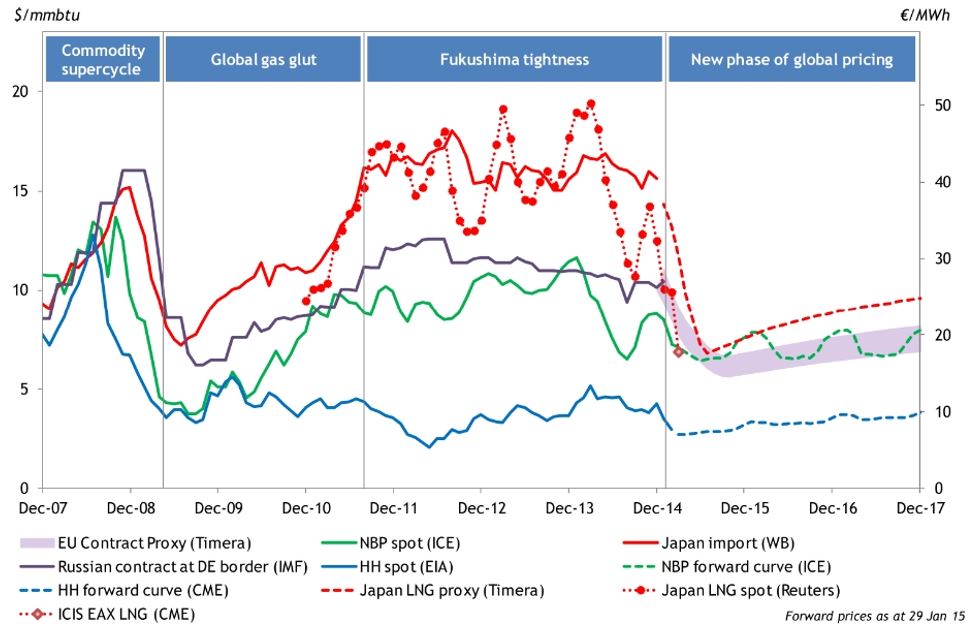

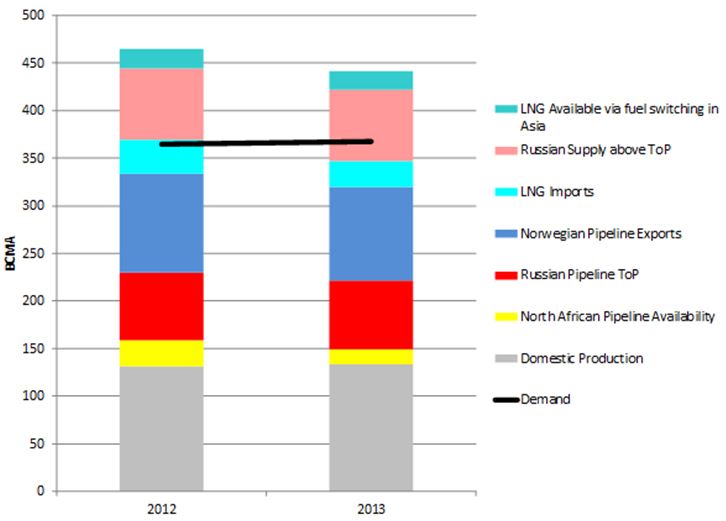

Historical analysis shows the framework approach to have worked reasonably well to the beginning of 2014, as shown in Figure 1. For 2012 and 2013, the annual average NBP price was $9.36 and $10.63/mmbtu respectively.

Figure 1. A Supply Stack for North and Central Europe, 2012 and 2013

Source: Rogers & Stern, OIES

Two areas that are more challenging with the framework approach from a practical viewpoint are:

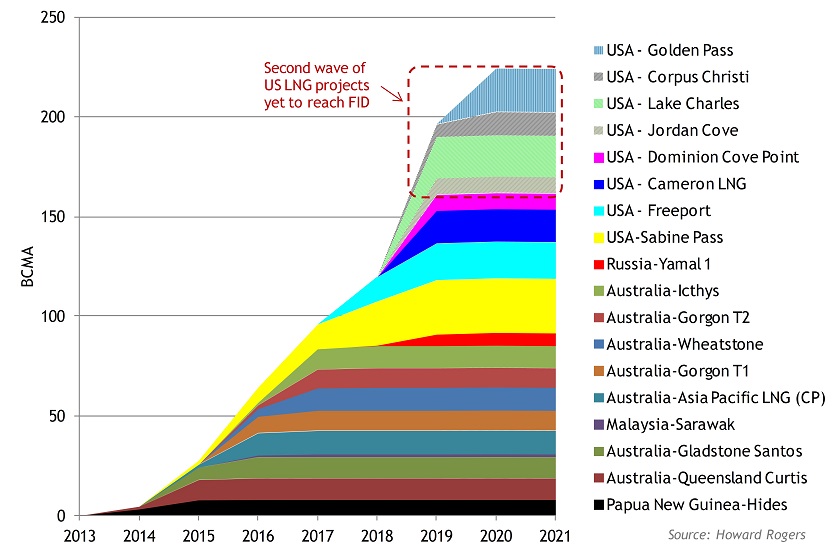

- In order to project the volume of LNG available for Europe, it is necessary to evaluate the global balance of LNG supply and demand which is subject to a significant degree of uncertainty.

- With the introduction of ad-hoc concessions on price formulae, take or pay levels and rebates relative to hub prices on an individual contract basis, it is extremely difficult to define what the ‘Russian contract oil-indexed price’ is.

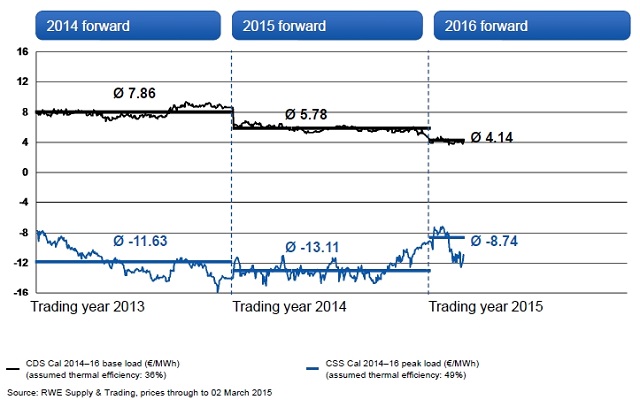

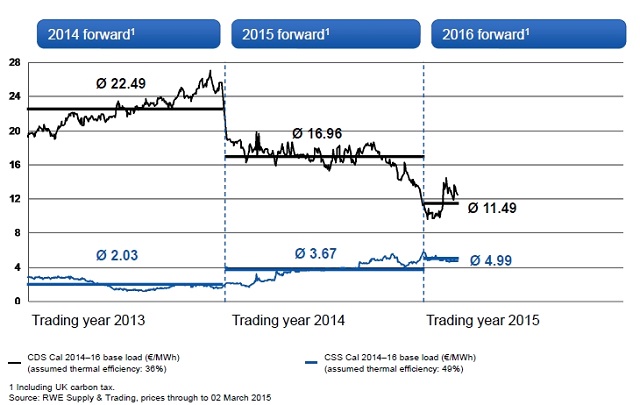

In early 2014, continuing to the present time, hub prices have fallen and remained below estimates of Russian contract price based on historic relationships to lagged oil product pricing. In mid 2014, NBP fell to levels where it demonstrably displaced coal in the UK power market. The forward curve for NBP and TTF appears to broadly re-converge with the consensus view of Russian contract prices in the 2nd half of 2015. But if substantial volumes of LNG keep flowing into European hubs, realised spot prices may again fall below contract price levels (a risk which we explored last week). We will return to the price exposure risks for midstream companies presently.

Evolution of European gas players

At the birth of the continental European gas industry the challenges in introducing natural gas as a new fuel were essentially to establish:

- a pricing mechanism which would price gas into the energy mix at an advantageous level relative to oil products (without undue market disruption); and,

- national (or sub-national regional) champions (monopolies) to contract supplies from domestic and increasingly foreign producer/suppliers on a long term basis such that the financing of pipelines and distribution systems could be undertaken.

With the continuing strong growth in European gas demand up to the mid to late 2000s, this model proved highly successful for upstream and midstream participants. Demand growth effectively passed on the residual price risk to end consumers (power generators and industrials), who until relatively late in the day were unaware of this.

In the 2000s however, the First and Second Gas Directives, the Energy Sector Enquiry and the subsequent Third Package and Gas Target Model resulted in radical changes to the status quo. Network unbundling, entry/exit tariffs for transportation and the end goal of delivery of gas to hubs represented significant changes to the regulatory landscape. At the same time and partly in response to such changes, a wave of mergers created pan-European players. Significantly these were primarily power and gas utilities, dominated by power generation and management teams with more of a ‘trading mentality’.

In this new landscape the following changes can be observed in the roles of the key players in the gas supply chain:

- Producers and Exporters: Their primary role is largely unchanged; however they now have the option to sell directly to large end-users – either via medium term contracts or as trading counterparties on the hubs. They may wish to continue with existing long term contracts and to sign new contracts if undertaking large new upstream projects.

- Network Companies: Transmission System Operators (TSOs) and Distribution System Operators (DSOs): These are new players, the product of unbundling pipeline assets from the Midstream Gas Companies. They enjoy low (regulated) rates of return but bear arguably little risk.

- Local Distribution Companies: Although they have lost their physical networks, LDC’s have not yet been subject to serious competition for their ‘captive’ customers due to low levels of customer switching.

- Mid-Stream Gas Companies: These became the gas departments of energy utilities. They retained their long-term supply and transmission contracts. The supply contracts are subject to continual arbitration/renegotiation with upstream producers (unless they have been changed from oil- to hub indexation). The customer base is under attack from upstream producers and downstream LDC’s. Depressed demand also serves to increase the risks of not achieving take or pay commitments as well as creating potential financial exposures on send or pay in long term transmission capacity contracts.

The market landscape evolution described above has served to migrate risks into what were formerly Mid-Stream Gas Companies. The challenge they face is to continue to generate a margin on sales volumes given:

- A flat or at best low demand growth environment and competition for market share from LDC’s and new entrants.

- The exposure to price on their contracts with upstream producers (and the continual management distraction of renegotiations and arbitrations), if these have not been moved to hub indexation.

- The need to meet take or pay and send or pay commitments in supply and transmission contracts.

- The costs incurrent, not just in terms of sales management overhead but also the cost of transporting gas from the delivery point to the customer or hub.

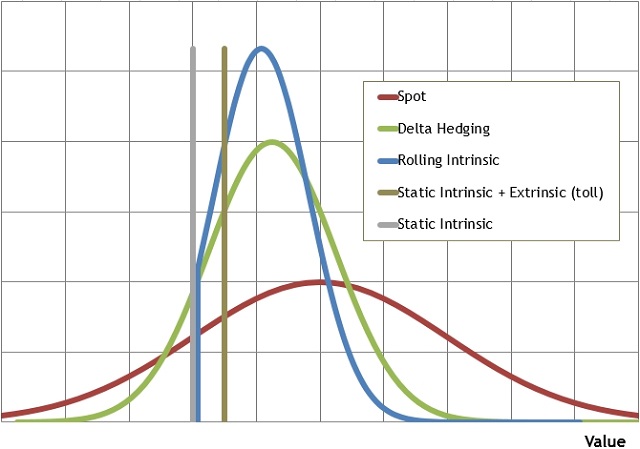

Exposures can be mitigated (but not always eliminated) by trading portfolio optimisation for the liquid portion of the forward curve. But the midstream players effectively need to pay a ‘hub minus’ price to the producers on the basis that they supply an aggregation function which has inherent value. At present it is not clear:

- Whether an upstream producer with an in-house trading capability recognises the value of aggregation versus direct hub sales; and,

- Whether exposure to midstream risks through intense mitigation activity is sustainable for the remaining life of long-term supply and transmission contracts, some of which run into the late 2020s.

European gas players looking forward

Looking to the future, there are three scenarios that can be envisaged:

Scenario 1: The ‘hub-minus model’ is successful and accepted by producers. Midstream players continue with a smaller but profitable merchant business and with some difficulty are able to continue with their long term contracts to expiry.

Scenario 2: The ‘hub-minus model’ is not accepted by producers. Midstream players are unable to establish a profitable business and cannot continue to the end of their long term contracts. Intense competition results in a consolidation, with companies leaving the sector leaving 6 or fewer serious players (‘the British model’).

Scenario 3: The existential threat to midstream gas players raises governmental concerns in some countries where the collapse of long term supply and transmission contracts is viewed as unacceptable. Financial support in some form is made available to enable existing contracts to be managed until expiry.

The current level of hub prices in Europe (around $7/mmbtu) may help midstream companies in terms of demand stimulation and meeting take or pay (or send or pay) commitments. However some of the problems described above primarily relate to the spread between oil indexed contract prices and hub prices. Although such spreads may reduce in the second half of 2015 it is difficult to predict whether this will be reflected in the spot market at that time or whether such a convergence will endure. The inability of players to hedge exposures beyond the liquid portion of the forward curve will unfortunately ensure that such problems are likely to recur throughout the remaining life of these contracts.

This article was drafted by Howard Rogers and is based on the findings and conclusions of the following paper:

The Dynamics of a Liberalised European Gas Market: key determinants of hub prices, and roles and risks of major players (Jonathan Stern and Howard V Rogers, OIES, December 2014).