Battery storage technology costs have been declining at an impressive rate over the last 2 to 3 years. Interest in the investment growth potential for electricity storage has increased sharply as a result. Much of this is being driven by enthusiastic projections for the mass market role out of batteries. There has been a particular hype around electric vehicle batteries, led by the pin up boy of battery evolution, Tesla CEO Elon Musk.

But it is utility scale electricity storage solutions that have the potential to make a larger and quicker impact on wholesale power markets. The major hurdle for broader commercialisation of storage technology is cost reduction. But the full force of US technology innovation is working on addressing this problem. Intense competition between technology providers is the driving factor behind rapidly falling unit costs. This has led to bold claims by some bank analysts that there may be significant rollout of utility scale battery storage by 2020.

Against this backdrop, we are publishing a series of articles on investment in electricity storage. In this first article, we provide a brief overview of different technologies as well as defining a set of key storage parameters that are common across all technologies. We then summarise the drivers of storage value and cost. Finally we set out the main challenges that need to be overcome to achieve broader commercialisation. We will then come back in subsequent articles to look in more detail at the economics and potential market impact of storage investment.

Electricity storage technology

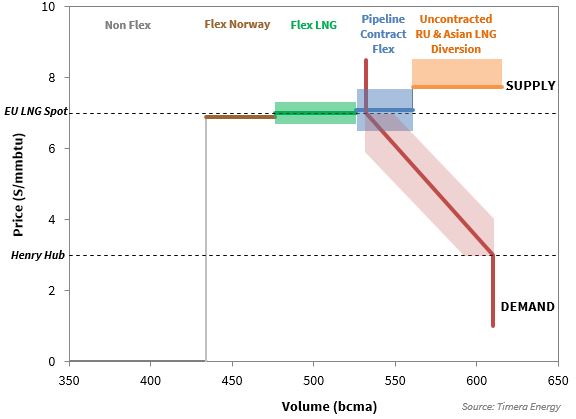

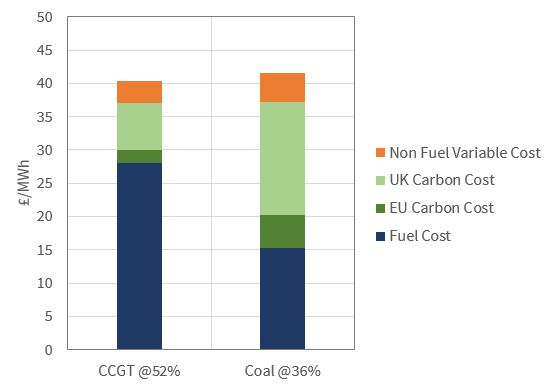

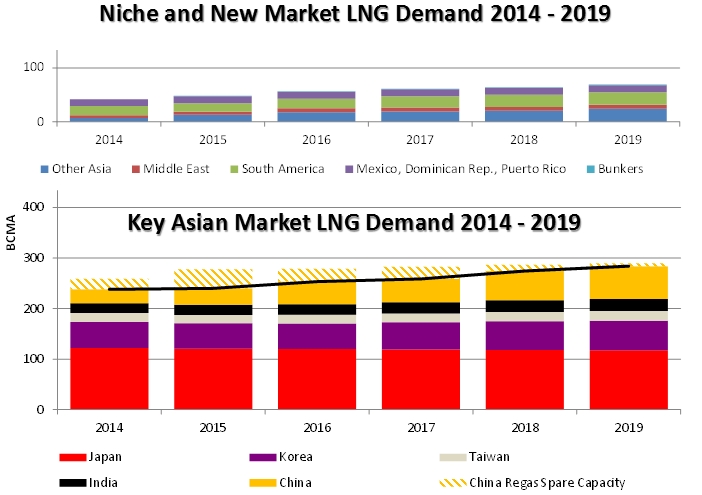

Utility scale electricity storage is not a new concept. Storage solutions have been commercially applied for decades, most commonly in the form of pump storage hydro assets. But the recent pickup in investor interest is focused on a number of emerging electricity storage technologies. These utilise a range of different methods for storing electrical energy as summarised in Chart 1.

Chart 1: Summary of electricity storage technologies

Source: Deutsche Bank, State Utility Forecasting Group

Developers are competing against each other and the clock to develop a commercially viable utility scale storage solution. The most promising signs of technology evolution are focused on the electrochemical category in the chart given rapid recent declines in the unit costs of battery storage.

We do not address the pros and cons of different technologies in this article. Instead we focus on defining a common set of parameters which can be used to characterise the performance of any storage system. Ultimately it is these parameters that will interact with wholesale market dynamics and cost structure to define the investment case for any particular storage project.

Storage physical characteristics

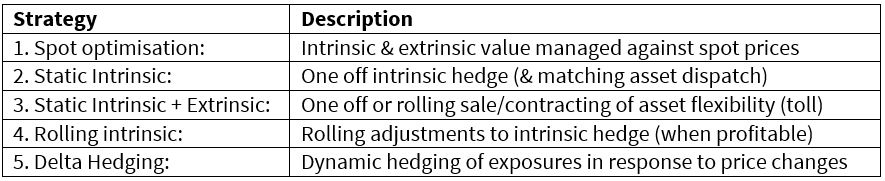

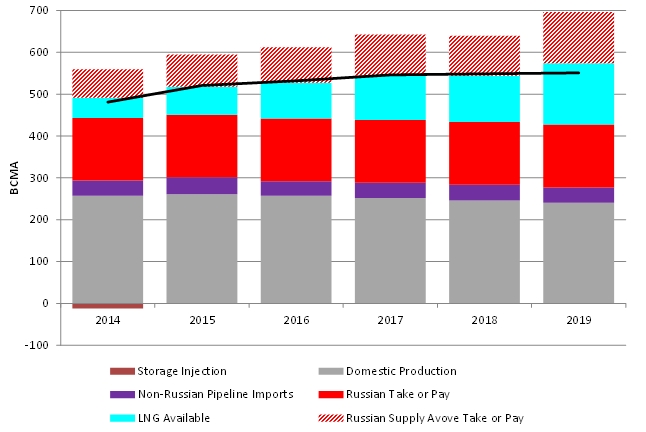

There are four key parameters that can be used to characterise any electricity storage technology (regardless of whether it is e.g. mechanical, electrochemical or thermal). These parameters are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Key electricity storage asset parameters

It is important to recognise the differences between a controllable generation asset (e.g. a thermal power plant) and a storage asset. Conventional generation assets are typically capacity constrained not energy constrained i.e. they have access to ample fuel supply (to convert into electricity) but are constrained by maximum capacity (or output). In contrast, the primary constraint for storage assets is the volume of stored energy rather than capacity to discharge energy. This is a commonly understood characteristic of hydro reservoir assets, but it applies equally to other forms of electricity storage e.g. batteries.

Storage value dynamics

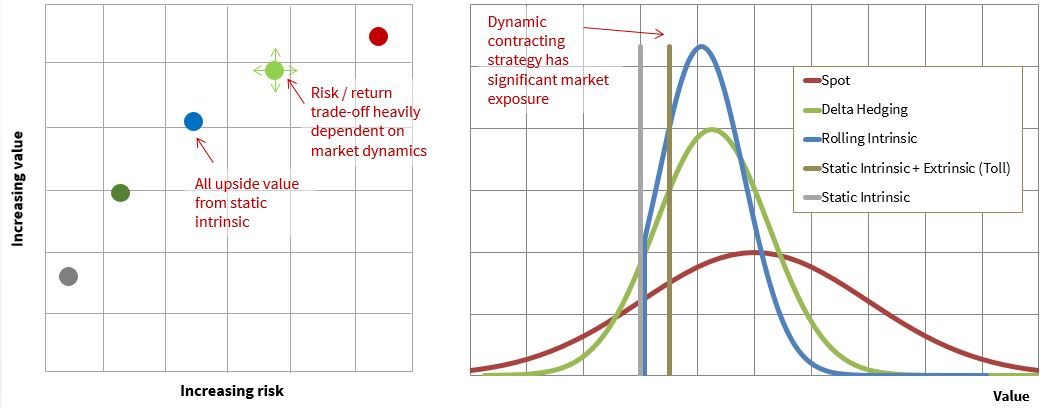

The investment case for an electricity storage asset is driven by the interaction between the physical parameters described above and the dynamics of the market in which the asset is deployed. As with gas storage assets, the primary value driver of electricity storage assets is typically the ‘merchant value’ associated with the charging/storing of electricity in low priced periods and discharge/release of electricity in higher price periods.

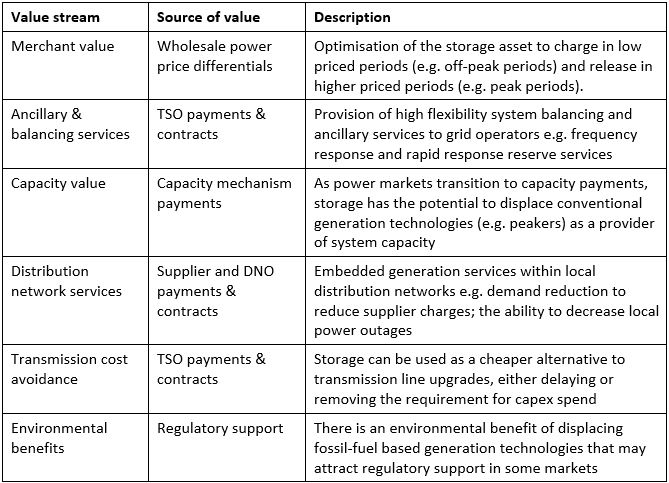

But in contrast to gas storage, there are a number of other drivers of electricity storage value that combined have the potential to be as important as the merchant value. The different electricity storage value streams are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2: Electricity storage value streams

Storage has well defined access to the first two value streams (merchant & ancillaries) via existing revenue streams in wholesale power markets. Storage should also have good access to capacity payments as these evolve.

However access to value becomes more complicated for the other value streams. This is particularly true of some of the more unique benefits that storage can provide to transmission and distribution networks (e.g. capex cost avoidance and increased reliability). It is these areas where policy evolution will be required to facilitate a clearer price signal if storage is to access potential value (e.g. through evolution of regulated cost recovery mechanisms for TSOs and DNOs).

It is also possible that some market regulators will implement regulatory support to remunerate the environmental benefits of storage technology (e.g. in displacing thermal power generation).

While in theory storage appears to benefit from a diverse range of value streams, these may not be independent and additive. In other words benefiting from one value stream (e.g. merchant revenue) may inhibit access to other streams (e.g. transmission & distribution benefits).

However what is encouraging about storage from an investment perspective is that, unlike renewable technologies, the first five storage value streams in the table above are not driven by consumer subsidies. In other words, storage commercialisation should be possible on a standalone basis if value can be practically monetised and projected cost reductions can be achieved. But there are a couple of key ‘ifs’ in the previous sentence.

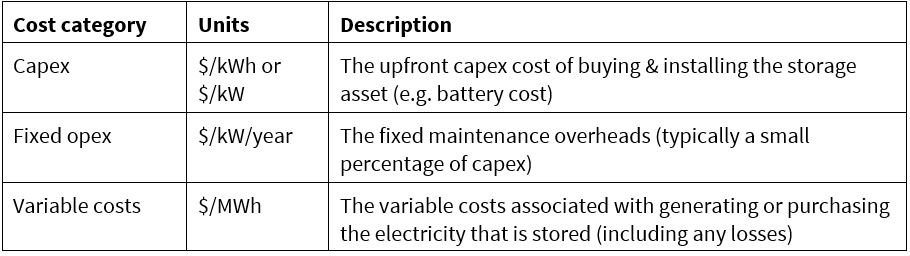

Storage cost dynamics

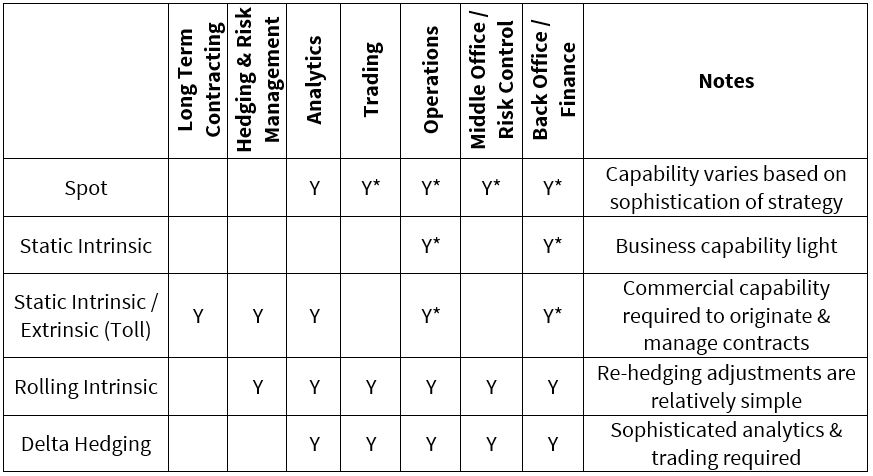

The costs of storage investment can be split into three broad categories shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Electricity storage cost categories

It is important to note that for battery storage, the operational pattern of battery usage is important in defining its cost structure e.g. whether usage is focused on fast cycling to capture price differentials or providing network support services. There can also be significant non-battery capex costs associated with developing the storage system.

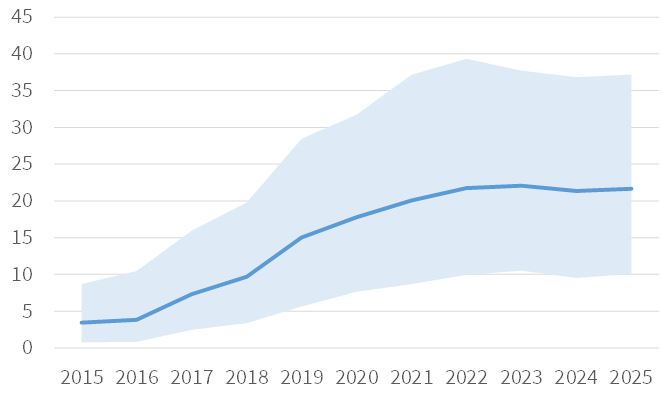

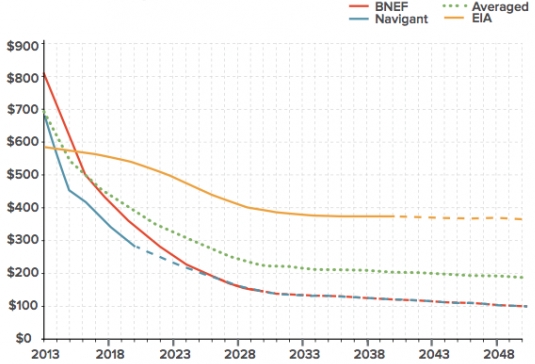

Capex costs are typically measured on a $/kWh stored energy basis, with current costs ranging upwards of 500 $/kWh. But investor focus is particularly on the potential for battery storage costs to fall rapidly over the remainder of this decade. A viable investment clearly depends on number of other factors as well as capex. But a commercialisation hurdle for storage costs of around 200 $/kWh is commonly cited as a reasonable benchmark.

Chart 2 illustrates shows some examples of published cost reduction curves for battery storage. We do not show this chart as an accurate representation of future storage costs, but rather to illustrate the aggressive cost reduction curves currently in circulation. The differences in forward projections illustrate the inherent uncertainty around technology cost reduction. What is clear however, is that battery storage is currently driving down the steep section of the cost reduction curve.

Chart 2: Example of projected battery storage cost reductions

Path to commercialisation

Unlike renewable technologies, the major hurdle for storage investors is not gaining access to consumer funded regulatory support. Commercialisation of storage is likely to require cleaner regulatory definition of price signals. But broader commercialisation will need to happen on a standalone basis.

The key challenge in building an investment case is to access a set of revenue streams that will support investment costs and financing, within a palatable risk/return boundary. This relies on more than just a cost competitive source of storage capacity. It also needs to be built on a realistic view of the interaction between the physical parameters of the storage asset and the monetisation of different revenue streams in the market in which the system is employed. Given the challenges described above, we suspect early deployment of storage will be focused on particularly compelling localised opportunities e.g. ancillary services or embedded benefit payment streams that can be clearly monetised without adversely inhibiting the capture of merchant revenue.

In order to define and analyse electricity storage investment opportunities, it is useful to develop a framework that overlays the physical, value and cost parameters set out in Tables 1 to 3 above. This supports the consistent assessment of storage investment opportunities across different technology types and different wholesale power markets. We will come back to look at the investment economics of electricity storage in more detail in our next article in this series.

Article written by David Stokes and Emilio Viudez-Ruido