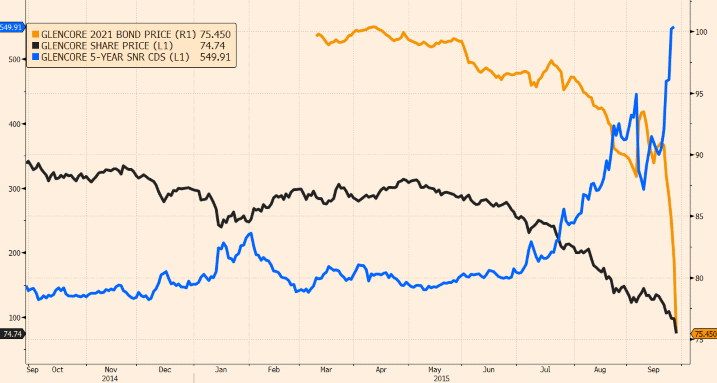

Last week we looked at the threat of a systemic credit event in energy markets. Market prices are flashing a warning signal about the capitalisation and interrelated exposures of a number of large commodity trading firms.

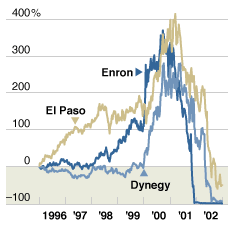

However you assess the imminence and magnitude of the current threat, historical evidence shows a clear track record of systemic credit events. We looked at the 2001-03 Enron collapse last week as a case study. The events at the peak of the financial crisis in 2008-09 are another example. So rather than waiting to see if ‘commodity traders 2015-16’ is the next occurrence, what defensive preparations can be made in advance?

Issues with credit risk management in energy companies are often rooted in the basics. For example:

- Ensuring the robust definition & measurement of credit exposures

- Making sure these are reflected in commercial decision making and the ongoing management of counterparty exposures.

Credit risk management problems are often driven by an under-resourcing of credit risk functions, given the perception that they are just a cost centre or administrative control function. There can also be challenges within large energy companies when it comes to managing credit risk within business units (e.g. trading functions) versus the management of broader corporate credit exposures.

On a day to day basis credit risk may appear relatively dormant compared to market risk. But every once in a while it rears its ugly head and the scale of losses can dwarf those of more closely regulated market risk exposures. This means that credit risk is all about robust and efficient practices that provide a structural defence. Ramping up a focus on credit risk once a credit event is already in motion smacks of closing the stable door after the horse has bolted.

Defence in two steps

Building a basic defence against credit risk can be broken down into two key parts: (i) measures in place at the time of transaction and (ii) measures taken on an ongoing basis during the life of the contract.

Time of transaction: Company credit policies should dictate which companies are permitted counterparties, and (via a system of exposure limits) to what extent. Within this policy framework, the application of a Credit Value Adjustment (CVA) ensures that credit risk is priced into transactions on a deal by deal basis. CVA is calculated on the simple principle that a buyer of poor credit standing gets charged more than a strong buyer.

The CVA attempts to quantify the appropriate credit risk premium (or discount, when buying – recognising that credit risk is symmetrical in forward exposures). Its use is twofold:

- As a direct input into contract pricing

- As the basis for an internal transfer (actual, into a credit reserve; or notional for management accounts) to provide ‘self-insurance’ against the statistically expected losses arising from the portfolio.

Additionally, an extension of the CVA calculation generates an ‘at-risk’ number (sometimes called ‘CVaR’). CVaR is used in assessing how much of a credit limit is utilised by a transaction, and how much risk capital is represented by the deal. CVA is becoming common practice in energy companies, helped by an increased regulatory focus (e.g. IFRS 13).

Ongoing management: On a continual basis through the life of the contract, various practical steps are taken to update the calculation of, minimise, and manage the ongoing exposure. This exposure may actually be getting worse with time, as market conditions and/or general corporate weakness affect the counterparty adversely and call their commercial performance into question.

These steps include clearing, netting, bilateral margining and calling for collateral. Importantly they typically depend on the contract being written with good credit support terms.

Ongoing management of credit risk also falls back on robust definition, measurement & reporting of credit exposures. This requires an effective capability to analyse the future evolution of credit exposure, for example incorporating techniques such as:

- Potential Future Exposure (PFE): quantification of maximum expected credit exposure of a contract/portfolio for a given time horizon & confidence interval.

- Credit VaR (CVaR): quantification of default loss for a given time horizon & confidence interval.

These techniques are the building blocks of tracking and managing credit risk on both an individual contract and a net portfolio basis. The stochastic measurement of PFE for an example hedging contract is illustrated in Chart 1.

Chart 1: PFE measurement example

Source: Amsterdam Complexity

Direct hedging: In addition to these steps Credit Default Swaps (CDS) also provide the ability to directly hedge exposures to larger counterparties. But these are less commonly used by energy companies to manage day to day contractual credit risk. This is in part due to the complexities associated with exposure matching, pricing and management of CDS in relation to the underlying credit exposure.

Backing up principles with practicalities

The defensive steps described above make for a good routine credit risk management discipline. But energy companies face a number of practical problems in implementing these. For example:

- Default data: The analytical techniques outlined above (e.g. CVA, CVaR) require default data and other inputs that typically come from rating agency assessments. The 2008-09 crisis is riddled with examples of how rating agency analysis was found wanting (e.g. their analyses of capital adequacy). We would be surprised if similar issues did not arise during the next major credit event.

- Default measurement: Even good-quality default data understate credit/performance risk in a commercial sector like energy because they relate to bond default, and companies fail to perform under ordinary commercial contracts before (if ever) they default on bonds.

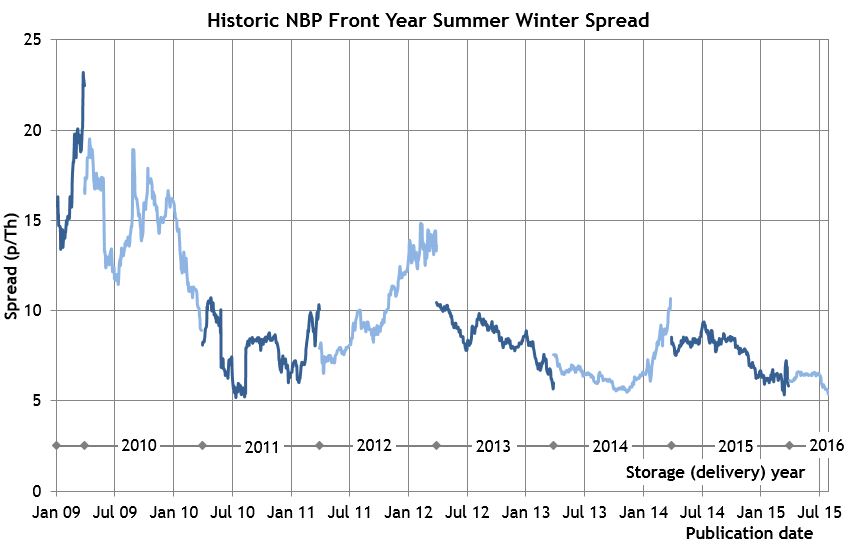

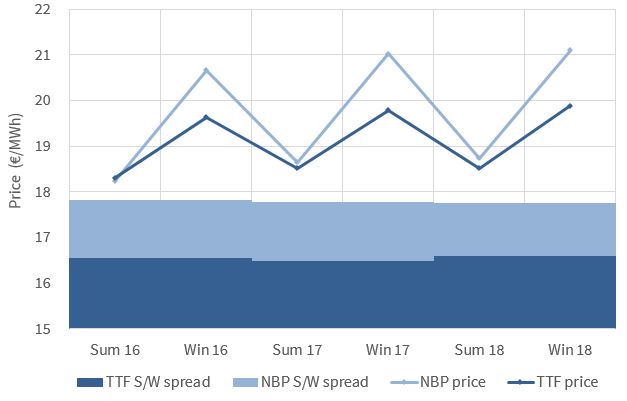

- Structural change: Many energy contracts have very long tenor, more so than in other industries. Looking back at events over the last decade (e.g. commodity supercycle, shale gas, financial crisis, Fukushima) illustrates that even ten years is a very long time. Structural changes in the industry over several years can systematically undermine the creditworthiness of large players or even whole sectors at a time.

- One shot defence: Although the credit support tools exist for inclusion in contracts, it is surprising how often companies fail to bolster their long-term contracts fully or allow credit terms to be negotiated away. There is generally only one opportunity to do this justice.

- Heritage: Some energy companies come to traded-market credit risk management from a retail/utility heritage. This can result in relative weakness and under-resourcing of credit risk management versus e.g. market risk management.

Common sense over black boxes

Analytical techniques such as CVA, CVaR & PFE can materially improve an energy company’s defence against major credit events. But relying too heavily on these tools can be dangerous as was illustrated in 2008-09.

Probabilistic methods to measure and price credit risk need to be applied in a transparent manner rather than as ‘black box’ number generators. Outputs also need to be challenged with a healthy degree of scepticism. If results cannot be demonstrated to company management via simple benchmarks & sense checks then it is likely that the methodology is the problem rather than the audience.

This leads to a final key element of credit risk management: stress testing. Systematic and carefully designed stress-test scenarios are vital in a regular, periodic programme of stress tests. Stress testing is a specific discipline with best practices of its own, but it is particularly relevant in credit risk management. A few obvious examples:

- What is the impact of the default of your largest counterparty (or top 3; or a sector of counterparties with interconnected exposures e.g. commodity traders)?

- What is the impact of counterparty default on key contracts, either from an individual asset or portfolio perspective?

- If 1. and 2. seem mundane then ‘reverse engineer’ a scenario that causes major portfolio stress.

- If unable to raise a sweat with 3. it is probably time to use a bit more imagination.

The creditworthiness of large commodity traders is likely to ebb and flow with the fortunes of commodity prices and broader credit market stress. But there is enough smoke on the horizon to justify a prudent review of credit risk management. In our view building a robust defence is about effective policy, CVA analysis & implementation and contract credit support at the time of transaction. Then on an ongoing basis this needs to be backed up by the measurement and management of credit exposures, bolstered with appropriate stress tests.

Authors: Nick Perry, David Stokes, Emilio Viudez Ruido