Long term contracts are a cornerstone of the energy industry. They play a key role in underpinning the capital expenditure required to develop assets. They also play an important role in ensuring security of supply.

There is a long history of contracting gas and power assets in Europe. The role of long term contracts has evolved with market conditions, availability of capital and changes in industry business models. This is particularly true for the contracting of flexible assets such as thermal power plants, interconnectors, pipelines and gas storage facilities, which typically involve the management of significant market risk exposures.

Long term contracts played a pivotal role in facilitating the development and acquisition of flexible assets through the early stages of European gas and power market liberalisation in the 1990s. The landscape then changed in the post Enron bust period of the early 2000s. A strong push for scale and vertical integration saw European utilities internalise flexible asset exposures within their portfolios. This has led to somewhat of a decline in the role and availability of long term contracts over the last decade.

But three factors are currently driving a resurgence in the contracting of flexible assets in Europe:

- Balance sheet weakness is increasing pressure on utilities & producers to divest flexible gas and power assets (E.ON and Vattenfall being two prominent recent examples).

- Cash rich infrastructure and private equity funds are looking to acquire these assets, but to outsource the majority of market risk via long term contracts in order to protect equity and avoid the overheads associated with setting up internal trading capabilities.

- More willing lenders are offering attractive financing terms given low interest rates and a hunt for yield, but are seeking long term contract protection to ensure adequate cashflow stability.

As a result of these factors we have seen a surge in activity to structure & value long term contracts on flexible assets over the last 12-18 months. Available contract terms are asset specific, depending on factors such as the level of intrinsic margin and underlying market conditions. But there are some key practical principles that apply more generally for the contracting flexible assets. Today’s article is the first in a series of articles that sets out these principles, using case study examples to illustrate how they work in practice.

Asset contracting is a risk/return decision

Any sensible consideration of long term contracting revolves around a risk/return decision. This means the risk appetite of the asset owner is usually the starting point for defining an appropriate contracting structure. Contract impact on asset risk is driven by three main attributes:

- Volume: the portion of an asset margin that are covered via contract

- Duration: the time horizon over which margin is contracted

- Price: the contract pricing terms in relation to the asset’s underlying market exposures e.g. fixed, collared, indexed

These terms can vary considerably across contracts. But a set of principles on risk/return apply across all contract structures.

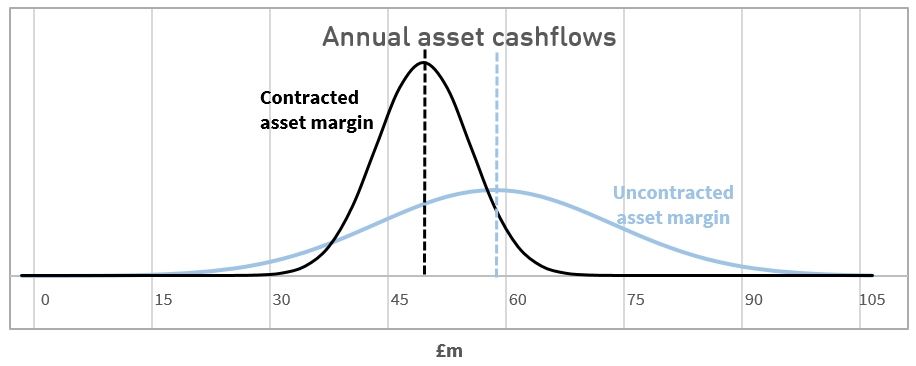

Consider the development of a new UK CCGT plant as an illustrative case study. Let’s assume the majority of capacity of the CCGT is contracted via a fixed price (annual capacity fee based) tolling contract. Chart 1 shows a simplified diagram of the impact of the contract on annual asset gross margins.

Chart 1: Contracted vs uncontracted asset margin distributions (UK CCGT example)

Source: Timera Energy

The blue line shows the frequency distribution of uncontracted (or merchant) asset gross margins. This distribution is relatively wide given the asset is fully exposed to market risk (i.e. to the market sparkspread). The black line shows the distribution of asset margins with the tolling contract in place. It should be noted that the distributions in the diagram are illustrative. In reality these will be driven by the relationship between a specific set of contract terms and underlying market price distributions.

The difference between the uncontracted and contracted distributions illustrates the main principles of asset contracting:

- Risk: Contracting reduces the variance of the distribution of asset margins, restricting downside but also limiting upside. In other words it reduces the owner’s risk of margin outcomes deviating from expected levels. For the CCGT asset example, the tolling contract acts to lock in a fixed capacity fee on a portion of asset flexibility value, reducing exposure to the market sparkspread.

- Return: There is no free lunch. Contracting also acts to reduce the expected level of annual asset margins. This is because the counterparty on the other side of the contract is forced to take on market risk and needs to be appropriately compensated to do so. In other words the counterparty applies a haircut (or discount) to expected margin levels. Quantification of this contract haircut is driven by factors such as market volatility, asset ‘in the moneyness’ and contract duration, which determine the risk capital required by the counterparty to support the contract.

There are many other considerations involved in successfully executing a long term contract. But understanding the risk/return impact of contracting is an important place to start. This is not a qualitative exercise, it requires numbers.

In other words it relies on the practical quantification of the impact of contracting on asset risk/return distributions. A failure to realistically quantify contracted project economics in advance of securing a capacity agreement has been one of the major road blocks that has stalled the Trafford CCGT development project in the UK.

Contracting to protect equity and debt

Equity investors in flexible gas and power assets can face a tough challenge in defining and securing appropriate volume, duration and pricing terms. The level of intrinsic margin or ‘in the moneyness’ of an asset is an important factor determining whether contracting makes sense. It is also a key factor determining lender willingness to provide debt.

This can be illustrated by looking at some examples of assets with different margin structures:

- Deep in the money: The interconnector assets that are being developed between Continental and the UK power markets benefit from high structural intrinsic margins. Forward power prices in the UK are currently at more than a 15 €/MWh premium to France and Belgium. Margin stability associated with the ‘in the moneyness’ of interconnector optionality acts to reduce long term contract price haircuts. It also means a greater portion of asset cashflow can be contracted to protect equity returns and secure debt.

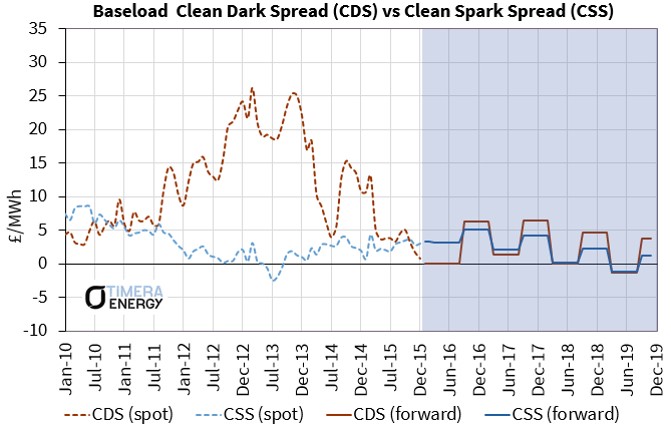

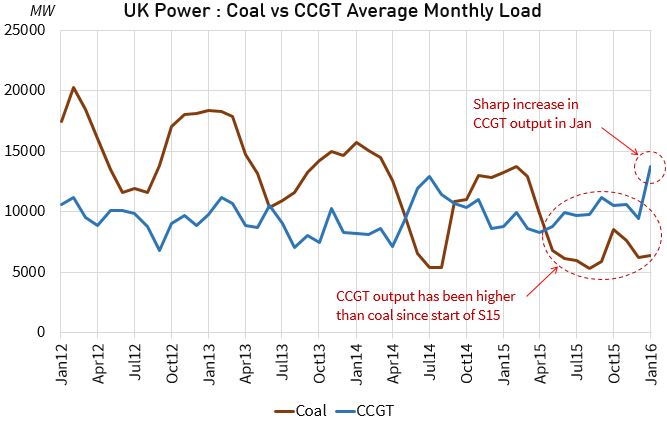

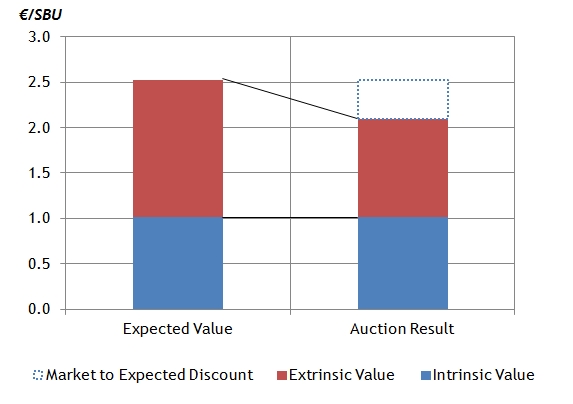

- Less in the money: A broad range of flexible European assets currently have some structural margin, but at levels that make contracting a challenge. These include gas pipeline, gas storage and some thermal power assets (e.g. UK CCGTs). The defining factor for a successful contracting strategy is ensuring that the associated reduction in risk adequately compensates for the reduction in asset return. This can be very difficult when contract buyers, typically energy trading desks, heftily discount contract prices to reflect the risks associated with a lack of intrinsic margin.

- At or out of the money: If an asset has little or no intrinsic margin (e.g. thermal power assets in Continental Europe) then contracting typically makes no sense. This is because the return on these assets is driven by extrinsic value associated with market volatility or structural market recovery. Realising this value usually means adopting a merchant strategy rather than locking in weak returns via a long term contract.

Chart 2 illustrates some of the issues involved by returning to the UK CCGT tolling example. Expected asset return is the difference between expected gross margin (at the centre of the margin distribution) and the costs associated with plant opex and any debt servicing (shown via the grey and red bars respectively).

Chart 2: Structure of contracted asset return (UK CCGT example)

Source: Timera Energy

The merchant or uncontracted margin distribution (in blue) shows a significant risk of margin falling short of plant opex and debt service costs (i.e. distribution downside exposes debt/opex levels). Contracting acts to:

- Reduce downside risk shifting the tail of the cashflow distribution to the right and reducing the probability that margin falls short of debt service and opex costs.

- Reduce expected return moving the expected plant margin down from the blue dashed line (uncontracted) to the black dotted line (contracted) and reducing the level of asset return above costs.

Defining a contract structure that balances these requirements becomes more difficult the lower the intrinsic margin or ‘in the moneyness’ of the asset. This in a nutshell is the challenge facing European investors looking at flexible gas and power assets.

An investment and contracting case needs to be built around providing adequate downside protection for equity and any debt. But at the same time ensuring that an adequate expected return on equity can be maintained. This challenge is not an easy one to overcome given the decline in intrinsic margin of many assets. But it is driving the innovative evolution of both contracting and financing structures, a topic we will return to in our next article in this series.

The blog will take a one week break for Easter but we will be back on April 4th.

Article written by David Stokes & Olly Spinks