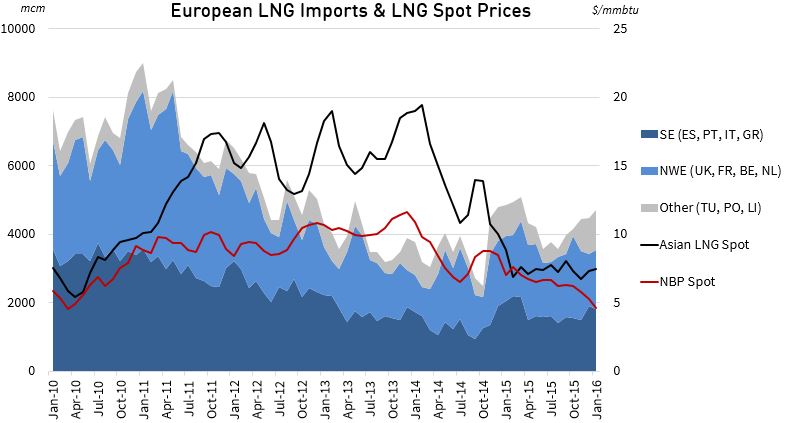

Over the 2016-19 period, LNG liquefaction capacity under construction is set to increase global LNG supply by approximately 150 bcma. Current rates of global LNG demand growth are not high enough to absorb this swell in new supply.

Europe will play a key role in balancing the global gas market, given the status of liquid European hubs as the ‘market of last resort’ for surplus LNG. In turn the impact of LNG flowing into Europe will be one of the key factors driving the evolution of European hub pricing dynamics.

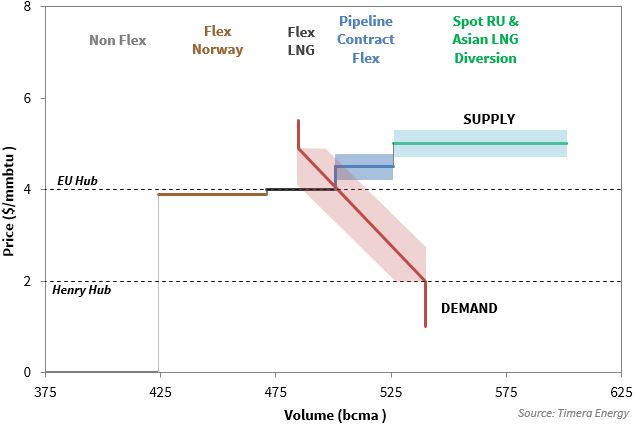

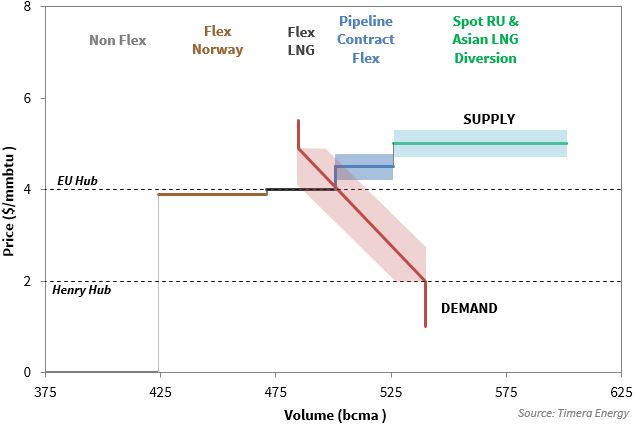

The switching of gas-fired power plants for coal plants is set to be the frontline mechanism that enables Europe to absorb more gas. But what incremental volumes of gas can the power sector burn, and how do these volumes change with market prices?

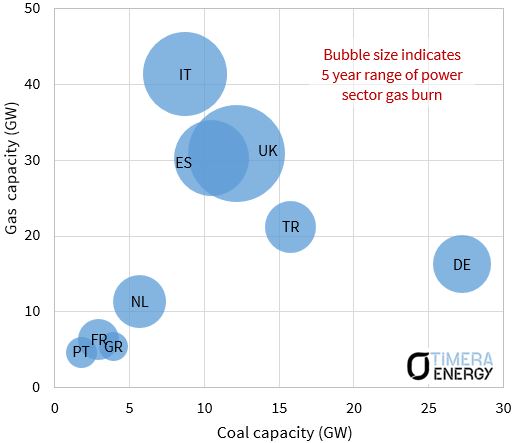

In last week’s article we set out and ranked the key power markets that drive the switching of gas for coal fired power plants in Europe. We also showed an illustration of the gas vs coal price boundaries which provide a benchmark for the market conditions required for switching.

In today’s article we transition from a comparison of individual power markets to look at an aggregate pan-European view. We do this in order to quantify the aggregate European switching volume potential and its relationship to relative gas vs coal prices.

Putting numbers around the switching problem

It is difficult to perform a robust estimate of aggregate gas vs coal switching potential in Europe without modelling the underlying dynamics of the individual power markets which drive switching. To enable this, we have set up a scenario in our pan-European power market model that reflects current forward market pricing for fuels. This provides a benchmark for aggregate power sector gas demand given current gas and coal market prices.

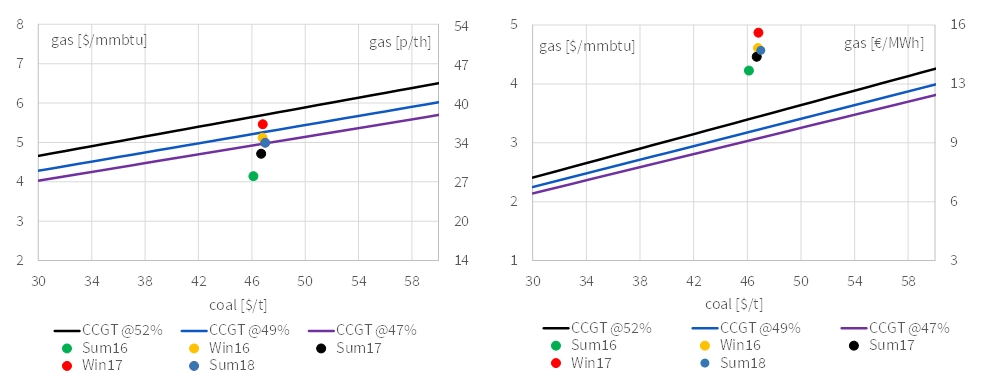

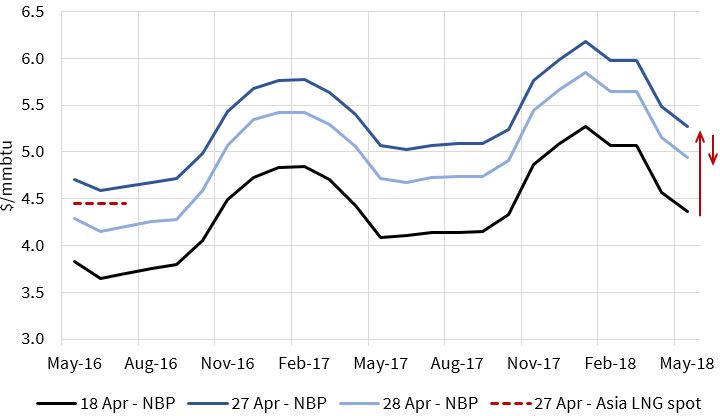

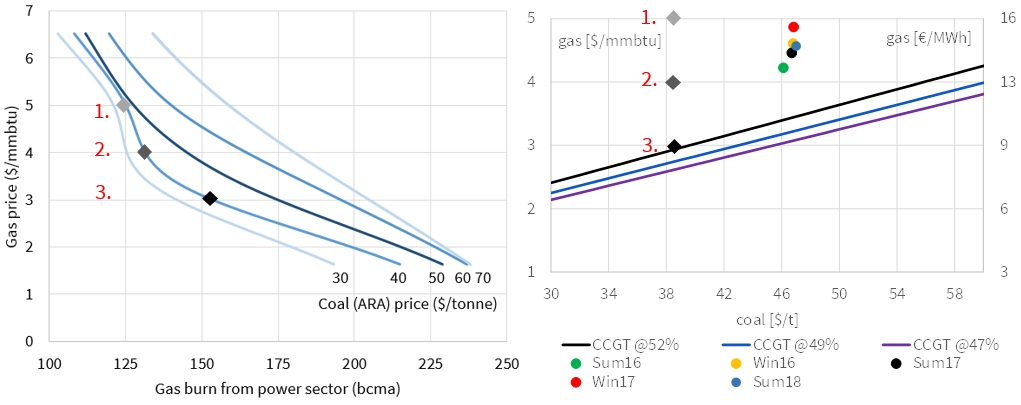

In order to analyse aggregate gas vs coal switching potential, we then run multiple combinations of gas and coal prices through the pan-European power market model. This allows us to produce gas switching demand curves for the different combinations of market prices shown in the left hand panel of Chart 1.

Chart 1: Aggregate European gas switching volumes vs market prices

Source: Timera Energy

Each line in the left hand chart can be thought of as an aggregate gas demand curve for the European power sector. In other words the lines show aggregate gas burn (bcma) as a function of gas price. Five different demand curves are shown for different coal prices.

The central (darkest blue line) shows switching dynamics at current forward coal prices for European delivery (approximately 50 $/t). As you move from left to right down this line, gas switching volume increases as gas prices fall.

We have then also produced demand curves for incremental changes of 10 $/t in coal prices away from the 50 $/t anchor case (shown as the other blue lines on the left hand panel). It is interesting to compare the shape of these demand curves at different levels of coal prices:

- Coal price 70 $/t: This switching line illustrates a scenario where coal prices rise around 20 $/t higher than current market levels. In this situation there is an almost linear relationship between gas prices and aggregate European gas switching volumes. This is because with significantly higher coal prices, gas-fired plants across Europe are broadly on equal competitive terms versus coal plants, with load factors and gas burn increasing steadily as gas prices decline.

- Coal price 40 $/t: This switching line shows a scenario where coal prices fall relative to gas prices, inducing a pronounced boomerang shape in the switching line. This shape relates to differences in capacity mix across European power markets. Some substitution of gas for coal plants occurs at higher gas prices (e.g. 5-6 $/mmbtu) in markets where CCGTs play a more dominant role in the capacity mix (e.g. UK and Italy). But in a price range below this (4-5 $/mmbtu), the rate of gas switching declines as gas prices fall, before increasing again at lower gas prices (e.g. 3-4 $/mmbtu). This is because larger gas price declines are required to trigger material switching in the Continental power markets which are currently dominated by coal generation (e.g. DE, NL). This can be seen via the Netherlands switching boundary chart in the right hand panel (which we showed last week), where gas prices need to fall towards 3 $/mmbtu to induce baseload switching of CCGTs for coal plants.

The demand curves shown in Chart 1 enable a more practical analysis of potential switching volumes in Europe given different combinations of gas and coal prices.

Switching volume response to absorb oversupply

In order to draw some conclusions on aggregate European switching volume potential it is helpful to consider two cases:

- An isolated gas price decline: This provides a useful upper bound for switching potential e.g. in a scenario where gas prices weaken as oversupply grows, but other commodity prices (e.g. coal and oil) stabilise around current levels.

- A correlated gas and coal price decline: This provides a more conservative estimate of switching potential assuming gas and coal prices decline together, but with gas prices falling at a faster rate than coal (as has been experienced so far in 2016).

European hub prices could fall another 1.00-1.50 $/mmbtu before truly converging with Henry Hub (as we set out here). If this occurred as an isolated decline in gas prices from current levels (a little above 4 $/mmbtu) it could generate an estimated 30-40 bcma of gas switching volumes.

If on the other hand coal prices declined in tandem with the 1.00-1.50 $/mmbtu fall in gas prices, for example to 40 $/t, then we estimate it could generate gas switching volumes of 15-25 bcma This is likely to be more like 0-10 bcma in the case of a more substantial decline in coal prices to 30 $/t.

Switching dynamics are a big deal for the European gas market. Switching volume behaviour is set to play a pivotal role in balancing the European gas market over the remainder of this decade. But European power sector switching is also a major concern for the global gas market.

The extent to which the European power sector can absorb surplus LNG may also be a key driver of US exports volumes and flows. If the growth in global oversupply exhausts the switching potential in Europe, the role of market of last resort will need to transition to North America. This would mean that US export shut-ins would be required to absorb additional surplus LNG.

Article written by David Stokes & Olly Spinks