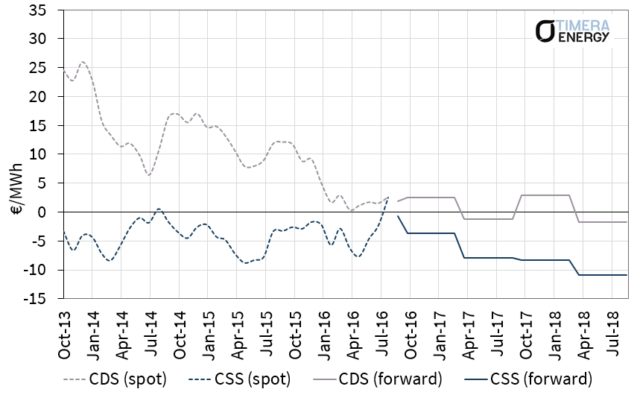

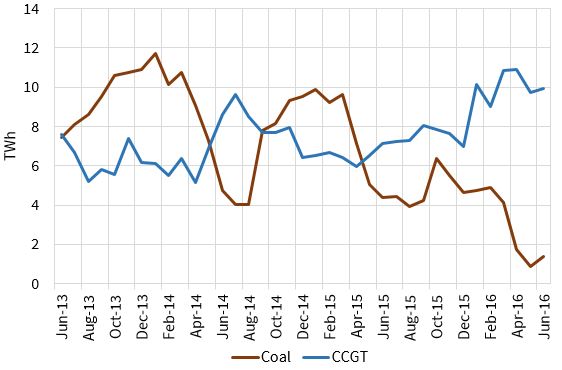

Some important structural changes are taking place in the UK power market supply stack. 2016 has seen a pronounced shift in favour of gas-fired generators. The flipside of the recovery in CCGT margins and load factors is that UK coal plants are being driven out of merit.

In last week’s article we looked at the changing fuel price relationships behind a recovery in the fortunes of CCGT plants across Europe. These same drivers are at work in the UK but are being magnified by three additional factors:

- A very tight UK system capacity margin

- The dominant role of CCGTs in setting power prices

- The UK carbon price floor

Excluding emergency reserve (SBR) capacity, the UK capacity reserve margin as measured by National Grid is now zero (0.1% if you want to be pedantic). In other words there is a significant possibility that system stress this winter will require Grid to call emergency reserve capacity to maintain security of supply. That prospect is now feeding through into forward spark spreads.

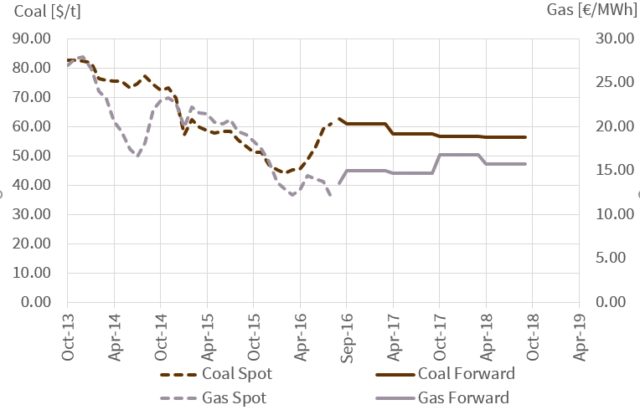

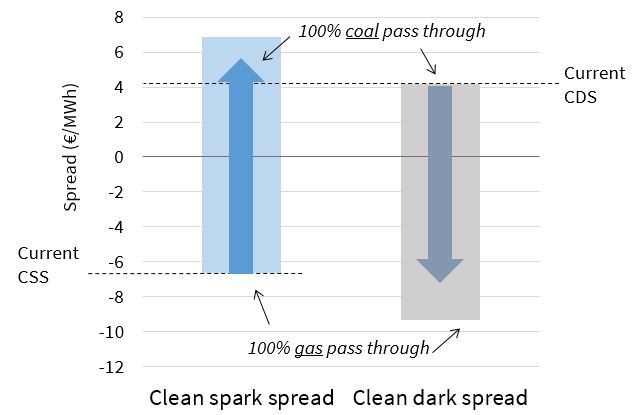

The price setting role of CCGTs in the UK has meant that falling gas hub prices in 2016 have had a direct impact in reducing power prices. The combination of falling power prices and the UK carbon price floor has sent spot UK coal plant margins well into negative territory.

Coal generators are now structurally out of merit in the UK. But coal units remain critical for UK security of supply until the Capacity Market starts to deliver large scale new gas-fired capacity from 2020. This leaves the UK’s coal units setting prices in the year-ahead capacity auctions at levels that allow them to cover fixed costs and avoid closure.

What is happening with UK generation margins?

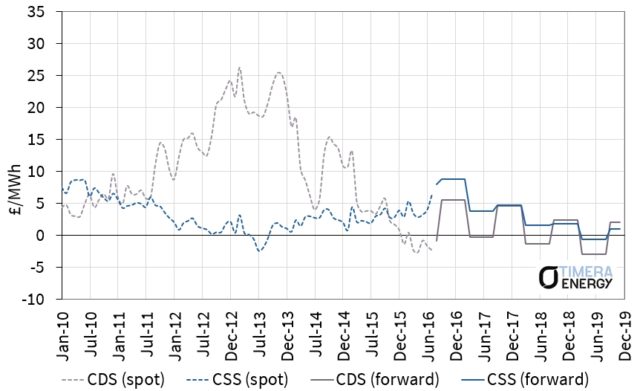

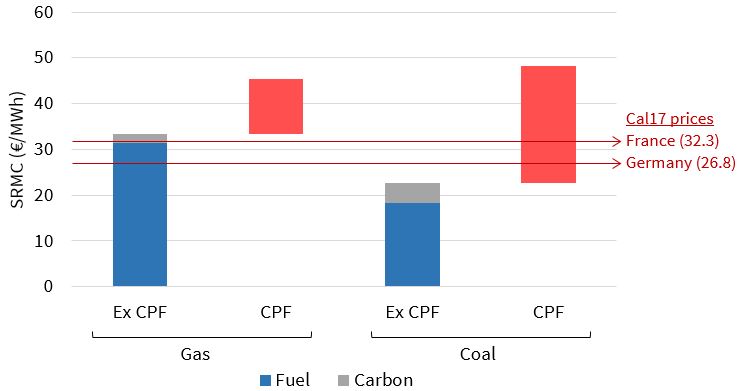

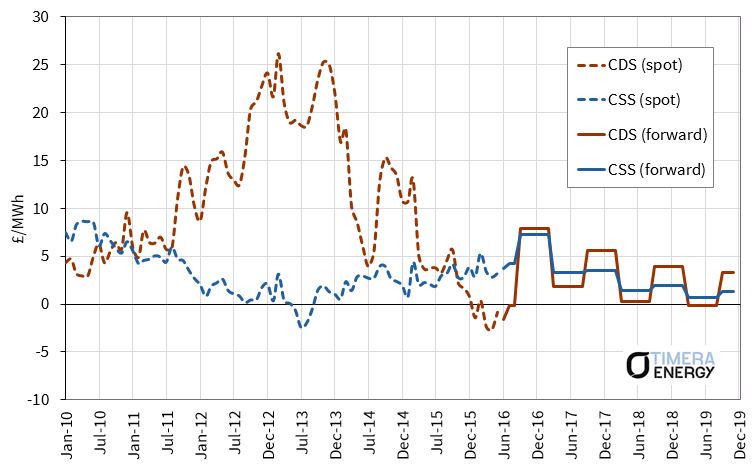

Chart 1 shows the historical evolution of spot CCGT and coal plant generation margins (CSS and CDS), as well as current spark and dark spread forward curves.

Chart 1: UK historical spot and forward CSS & CDS

Source Timera Energy (49% HHV CCGT efficiency, 36% coal efficiency)

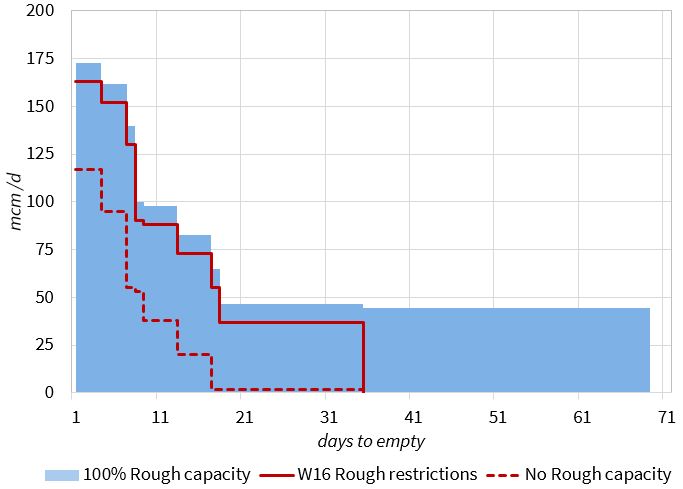

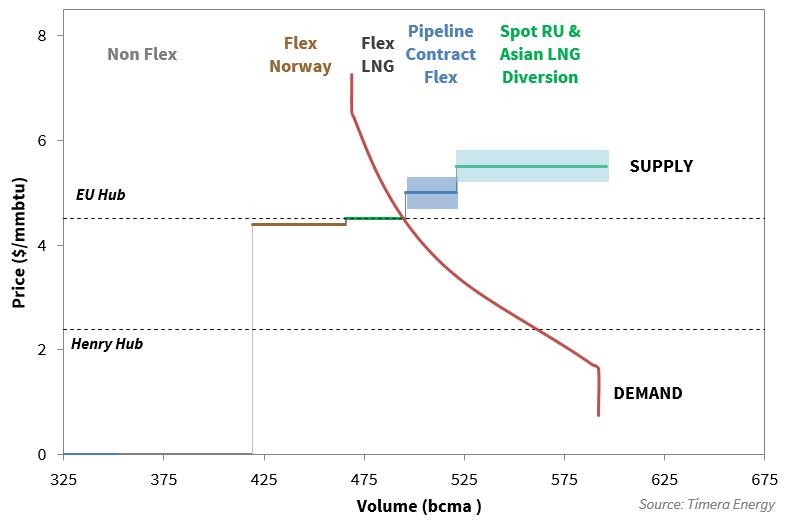

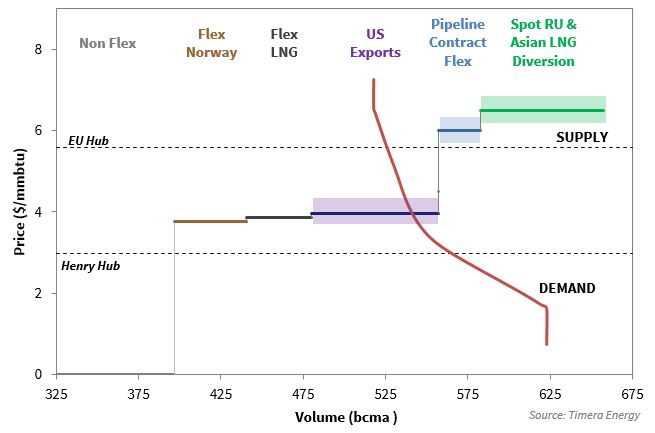

A sharp uptick in CCGT margins (spot CSS) can be seen in Summer 2016. This has been driven by falling gas prices given oversupply across European hubs (as explained last week). This oversupply has been particularly pronounced in the UK gas market because of the Rough storage injection outage.

Summer maintenance on Norwegian export lines to the Continent has seen gas diverted to the UK rather than have production shut in. Exports from the UK to the Continent in summer often run at maximum interconnector capacity anyway, and without Rough to soak up the resulting surplus, NBP prices have fallen to clear the UK market.

While these dynamics are an interesting short term phenomenon, there is a more important structural change taking place with spark spreads. The recovery in spot CSS across the summer has been accompanied by an increase in forward CSS, particularly for the coming winter (16/17). Winter CSS is now trading around 9 £/MWh, with average forward spark spreads over the next 12 months rising above 6 £/MWh. These levels represent a return to CCGT margins not seen since early this decade.

The events of 2016 have crushed coal plant generation margins. Spot baseload CDS has fallen into negative territory over the summer as gas prices have weakened. The CDS forward curve has so far just managed to remain in positive territory when measured on a market basis (i.e. only including fuel and carbon costs). But once variable coal transport and system costs are accounted for, forward baseload coal generation margins are also in negative territory.

As a result, the more efficient and flexible UK coal units have been relegated to a peaking role, eking out small margins from within-day price shape. Older coal units are sitting idle as reserve capacity.

Driving coal-fired generators out of the capacity mix was one of the key reasons for the UK government introducing the carbon price floor. The price floor in combination with shifting commodity prices has done that job well. But this has left the UK power market with a major security of supply issue.

Winter 16/17 – CCGT margins may recover further

Winter sparkspreads are foreshadowing what could be a more significant jump in spot outturn CSS this winter. The UK may be insulated from the risk of rolling blackouts by the 3.5 GW of Supplemental Balancing Reserve (SBR) capacity which the system operator (National Grid) has contracted over the coming winter. But SBR capacity does not participate in the generation supply stack and should only be called by Grid under threat of system emergency. This leaves room for the zero system capacity margin (ex-SBR) to drive significant increases in power prices and volatility to the benefit of CCGT margins.

The other factor that is helping UK CCGTs is the fact that coal plants are becoming more expensive on a variable cost basis. As well as covering variable fuel, carbon and system costs, coal plants also need to recover relatively high start costs. Because coal plant generation margins (CDS) are so weak, power prices are needing to rise in peak periods to incentivise coal plants to run. These factors act to drive increasing CCGT margin rents.

The UK will likely scrape through this winter without flickering lights given a 5% system reserve margin including SBR capacity. But it is the non-SBR zero reserve margin that will drive wholesale market pricing dynamics. The extent to which this translates into market fireworks will of course depend on variables such as cold weather, wind conditions, outages and performance of the debilitated Rough storage facility. But Winter 2016/17 is set to be the tightest period of the UK power market’s two decade history.

2017 and beyond

SBR will be discontinued from Summer 2017, with the new year-ahead 2017/18 capacity auction the mechanism used to procure an adequate system reserve buffer. This will have an important impact on wholesale pricing dynamics. Unlike SBR, capacity contracted in the year-ahead auctions will participate in the supply stack. In other words the units that make up the system reserve buffer will compete with other generators on a variable cost basis.

All other factors being equal, this should act to dampen power price levels and volatility when compared to the SBR scenario of Winter 16/17. But the relative behaviour of commodity prices will also play an important role. If weaker gas prices mean coal plants remain out of merit, then CCGTs may continue to earn healthy rents as coal unit variable & start costs act to increase power prices above CCGT variable costs.

Coal units will also play a key role in setting capacity prices in the next three year-ahead auctions (17/18, 18/19 & 19/20) before new supply comes online in 2020. Plants such as Fiddlers Ferry West Burton & Cottam are currently only recovering a fraction of fixed costs in the wholesale market. This means they will need to bid at capacity prices levels that allow fixed cost recovery in the year-ahead auctions. Competition to supply incremental megawatts will be particularly limited in 18/19 and 19/20 T-1 auctions given most generators already have capacity agreements from the four year ahead (T-4) auctions. Don’t be surprised if these auctions clear at a significant premium to previous ones.

Implications for asset owners & investors

The UK government is targeting the closure of all coal plants by 2025. It is unlikely that they will need to wait that long. The carbon price floor and the shifting relationship between gas and coal prices appear to be sending coal plant generation margins into terminal decline.

The UK may lose one or two more coal stations by 2018. But the remainder of the coal fleet is likely to remain on capacity market life support until 2020 when new gas plants come online. Despite being driven out of merit, coal units are set to retain an important influence on marginal pricing in both the capacity and wholesale energy markets over the next 3-4 years.

Coal plant woes are good news for UK CCGT owners. Structural gas price weakness and a tight system reserve margin are driving CCGT margin recovery. The relegation of coal in the UK merit order also means higher CCGT load factors, higher average efficiency and lower start costs. These factors contribute additional value over the headline spark spread recovery.

The recovery in the fortunes of UK CCGT plants is attracting plenty of investor interest. Utilities are eyeing the sale of existing CCGTs as a way of raising capital to sure up their balance sheets. And a bolstered capacity target for the December 2016 four year ahead auction has seen a frenzy of activity around CCGT development projects.

There have been a number of false dawns to the CCGT recovery story which has been anticipated for several years. Conditions for UK CCGT have improved steadily since gas prices started to weaken in 2014. But 2016 looks to be confirming the start of a more structural recovery.