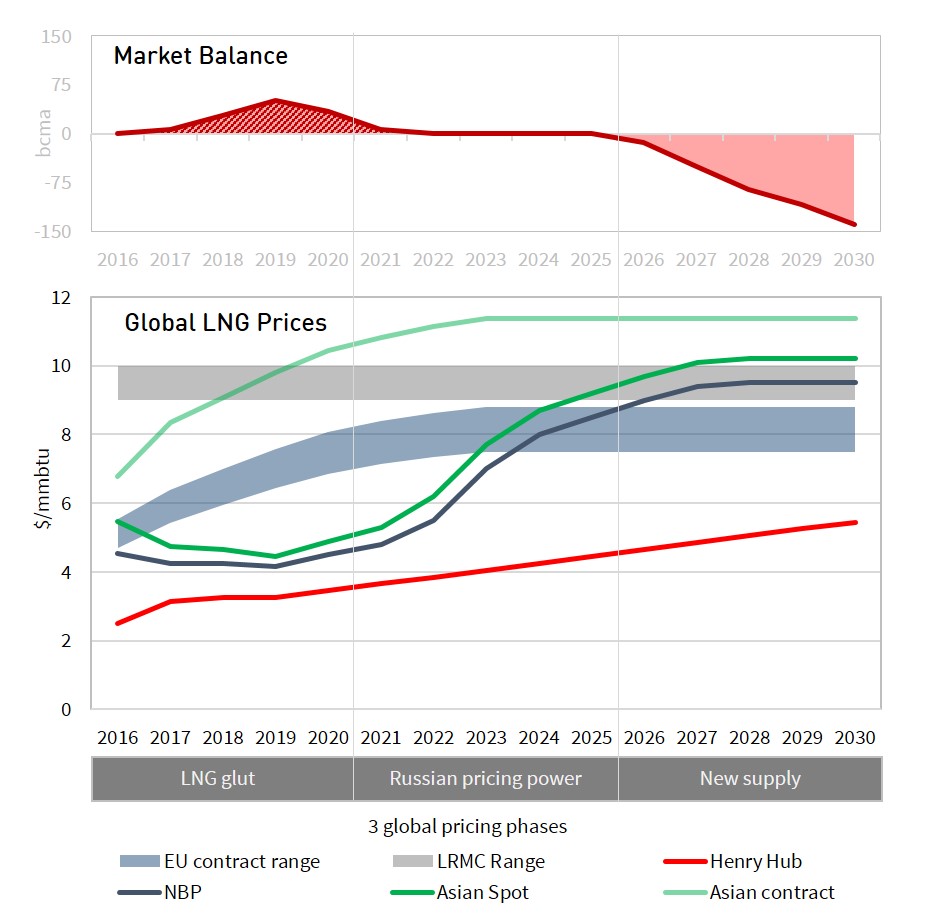

The global gas market has been shocked by the pace and scale of transition from boom to bust. At the beginning of 2014 suppliers were paying a lofty 20 $/mmbtu for LNG in a market that was anticipated to remain tight for years. By early 2016 producers were struggling to sell surplus cargoes for 5 $/mmbtu, 75% below the levels of just two years earlier. A bust of these epic proportions was not supposed to happen.

The initial shock has now passed and gas market consensus has digested the phenomenon of a state of global oversupply. But global demand growth remains sluggish and supply continues to grow. More than 50 bcma of new LNG liquefaction capacity has been commissioned since 2014. In addition, there is a visible pipeline of at least another 150 bcma of committed new capacity coming to market by 2020.

But as the dust from the bust starts to settle, attention is shifting to some key questions. How will the global market clear the evolving gas glut? And how will this impact the evolution of pricing dynamics and the gas market investment cycle?

Almost everyone in the gas and power industries has a vested interest in the answers to these questions, either explicitly or implicitly. In the next two articles we set out our take on the answers.

Global market rebalancing series

Rebalancing of the global gas market is a complex area with a heavy dose of uncertainty. But it is our view that the drivers behind market rebalancing can be broken down via a relatively simple logic. Over the next two weeks we set out our thesis on:

- The market mechanisms that will clear the current gas glut

- The path to global gas price recovery and why this may start sooner than expected

We will do this as much as possible using a practical scenario illustration of the evolution of global supply and demand volumes and regional gas prices.

In today’s article we focus on the key price/volume mechanisms that we believe will interact to clear the current market glut.

Evolution of the global market balance

In a nutshell, the current global oversupply of gas is the result of new LNG supply outpacing demand growth. Investment decisions in new liquefaction capacity earlier this decade were based on overly optimistic forecasts of demand growth, particularly in emerging Asian markets. The legacy of these decisions is still feeding through in the form of committed new supply, given relatively long delivery lead times for new liquefaction projects (around 5 years).

This overhang of surplus LNG is the primary driver behind the current global oversupply of gas. There are important domestic gas market dynamics at work behind this within regional markets across Asia, Europe and North America. But understanding how the global surplus of LNG can be cleared is a key starting point.

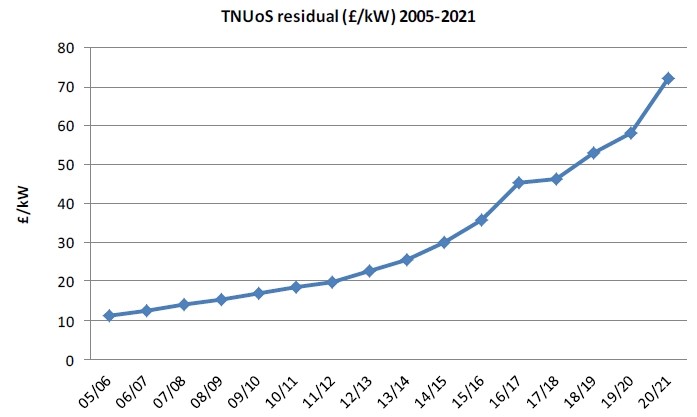

Chart 1 illustrates the LNG supply glut in the context of a scenario of the evolution of the global LNG supply and demand balance to 2030.

Chart 1: LNG supply glut and scenario evolution of global market balance (2016-30)

Source: Timera Energy

There is a cascading logic to the progression of the charts:

- Top chart: In the top chart we show a combined LNG market balance for non-European LNG importing nations. These consist of Asian importers plus ‘other’ smaller importers, predominantly in South and Central America. ‘Asian and other’ buyers typically have first call on global LNG supply, given demand is dominated by less flexible buyers with long term contracted volumes and LNG specific import requirements.

- Middle chart: The middle chart shows how LNG sits in the aggregate European gas market balance. Europe is broken out separately from other markets because it has liquid hubs, alternative supply sources and relatively flexible LNG supply contract structures. This means Europe plays an important role as a swing market to help clear the global LNG balance. Any surplus or deficit of LNG from the top chart (‘Asian and other’) can be thought of as cascading down into the European market.

- Bottom chart: Supply volumes in the top two charts assume LNG liquefaction capacity operates at full target production levels. Demand volumes assume ‘business as usual’ demand based on current market price levels. Any surplus or deficit of LNG that cannot be absorbed via European market swing flexibility under these conditions, creates a global LNG imbalance (surplus or deficit) shown in the bottom chart.

For simplicity the North American gas market is not explicitly shown in these charts, primarily because it is largely gas self sufficient (i.e. a net exporter of LNG). The US market however plays a very important implicit role in clearing an oversupplied global market which we set out in more detail below.

As growth in new LNG liquefaction capacity outpaces demand growth over the next three years, a growing global surplus of LNG emerges over and above ‘business as usual’ Asian & European requirements. The surplus in this scenario, peaking at 68 bcma (49 mtpa) in 2019, is represented by the red shaded ‘LNG glut’ triangle in the second and third charts.

The scale of the LNG glut is actually relatively small (e.g. versus aggregate European demand). But even small volumes of oversupply can induce big price moves in order to induce an adequate market clearing response.

It is important to note that while this glut triangle is a representation of LNG oversupply, the market will always clear. What the triangle illustrates is the incremental supply and demand response required to allow the global market to clear (versus a business as usual scenario). But what are the market mechanisms that act to clear this LNG glut?

Clearing mechanisms at work

Clearing the glut of LNG is about inducing incremental volume response. In other words, it is about inducing market participants to adjust the volume of their production and consumption decisions in response to market price signals.

In our view there are four key mechanisms that can drive this. Two of these involve incremental demand response (as a result of lower gas prices) and two involve the ‘shut in’ of price sensitive supply. The four mechanisms are summarised in Table 1 below, along with a range of potential volume response.

Table 1: Summary of four key clearing mechanisms to clear the global LNG glut

| Clearing mechanism |

Potential volume |

Volume dynamics |

Key price relationships |

| European power sector switching |

10-40 bcma |

Power sector gas demand increases as CCGT load factors increase at lower hub prices |

Relative gas vs coal price levels driving switching relationship between gas and coal plants |

| Asian demand response |

5-20 bcma |

Asian buyers (e.g. China, India) purchase incremental volumes as prices decline |

Available LNG purchase price terms vs alternative energy supply terms e.g. pipeline contracts, oil |

| Shut in Australian exports |

0-10 bcma |

Australian export volumes may fall if netback spot LNG prices don’t cover feed gas costs |

Netback cost of LNG sales vs variable cost of liquefaction feed gas |

| Shut in US exports |

0-80 bcma |

US export volumes may fall if netback spot LNG prices do not cover variable costs |

Premium of Europe and Asian spot prices vs US Henry Hub (+ variable transport) |

Source: Timera Energy

There is arguably a fifth clearing mechanism in the form of Russian production flexibility. The reason we have not specifically broken this out is that we assume that through the duration of the LNG glut, Russian acts to maintain its European market share (at around 150 bcma) rather than responding to prices. This is consistent with historical behaviour.

Our scenario summary on how the four mechanisms interact to clear the LNG glut shown in Chart 2.

Chart 2: Scenario projection of how 4 clearing mechanisms clear the LNG supply glut

Source: Timera Energy

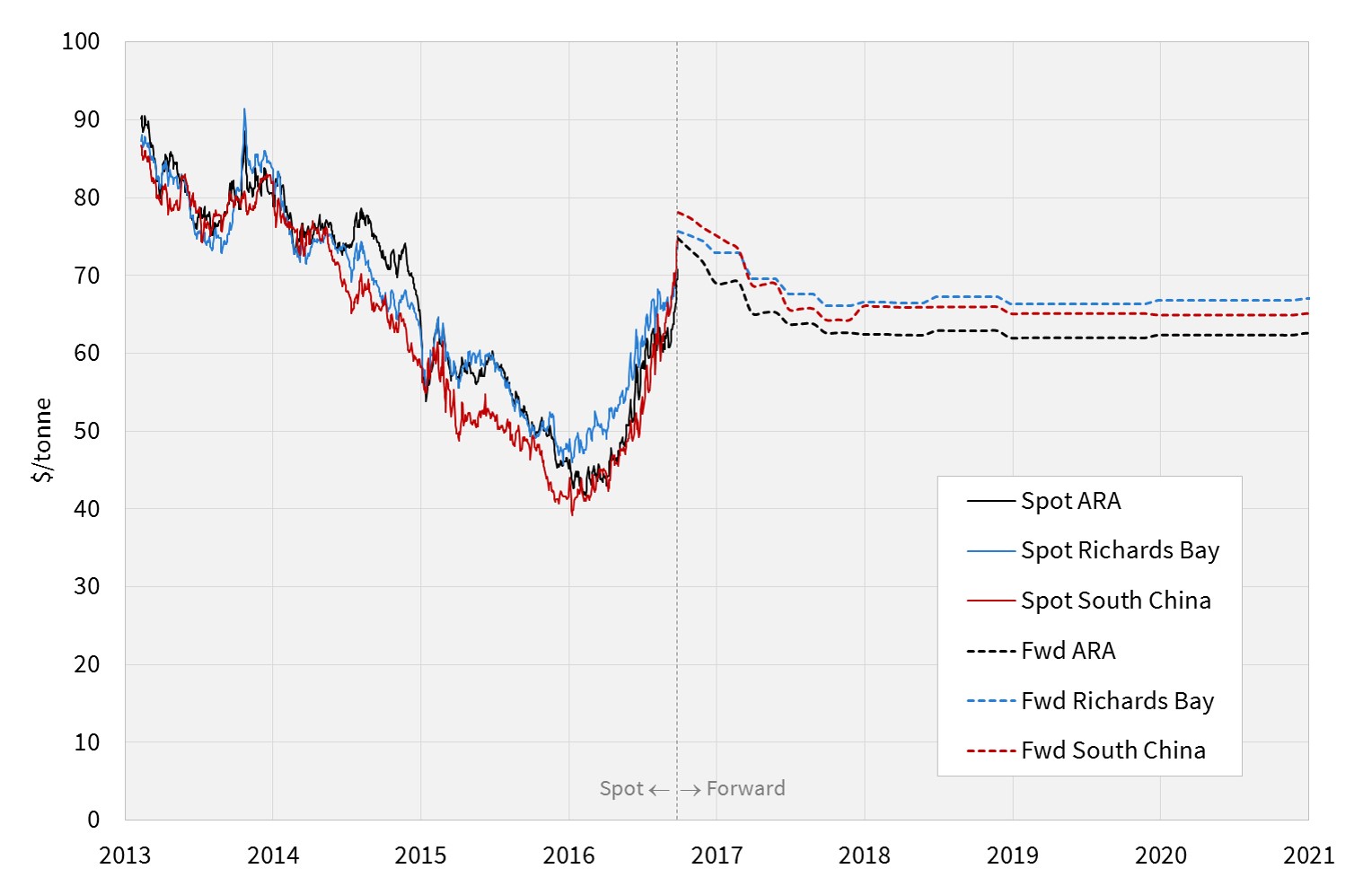

European power sector switching:

Clear evidence is emerging in 2016 of European power sector demand response to lower gas hub prices. CCGT load factors in gas dominated power markets such as the UK and Italy have risen substantially year on year. Even Continental power markets dominated by cheaper coal plants have seen switching to CCGTs over the summer.

There are two important price drivers behind this switching. A weakening of gas hub prices, caused in part by a steadily growing flow of LNG imports. Coal prices have also been recovering in 2016, lowering the gas price hurdle required to induce higher CCGT load factors.

European power sector switching is currently a key driver of marginal pricing dynamics across European hubs. It will also in our view be an important clearing mechanism as the LNG surplus grows (2016-19). We set out here why we think there may be up to 30-40 bcma of potential switching demand response in Europe. Some of this switching volume may end up being permanent, with weakening coal plant economics resulting in the closer of older coal assets (as is happening already in the UK).

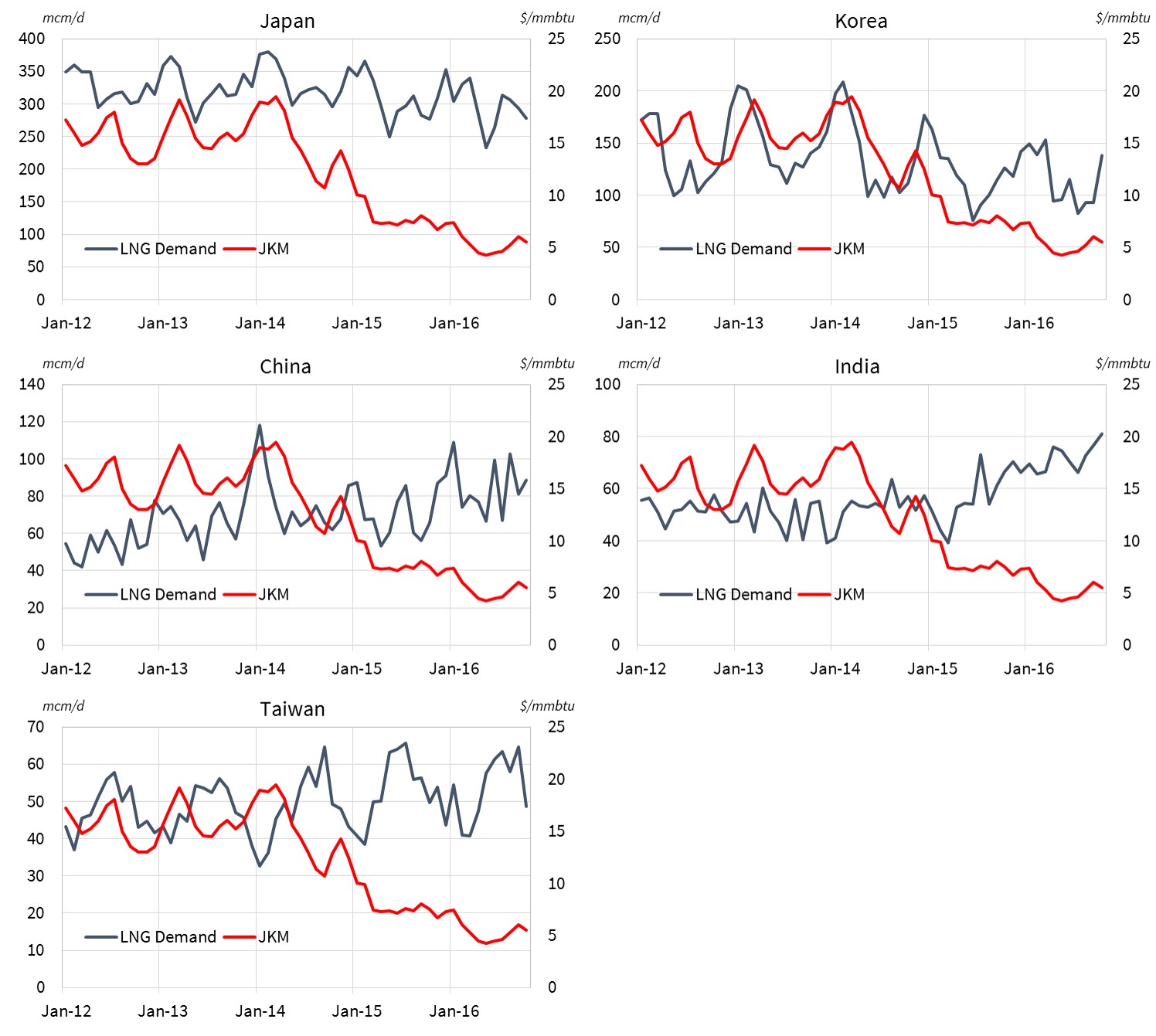

Asian demand response:

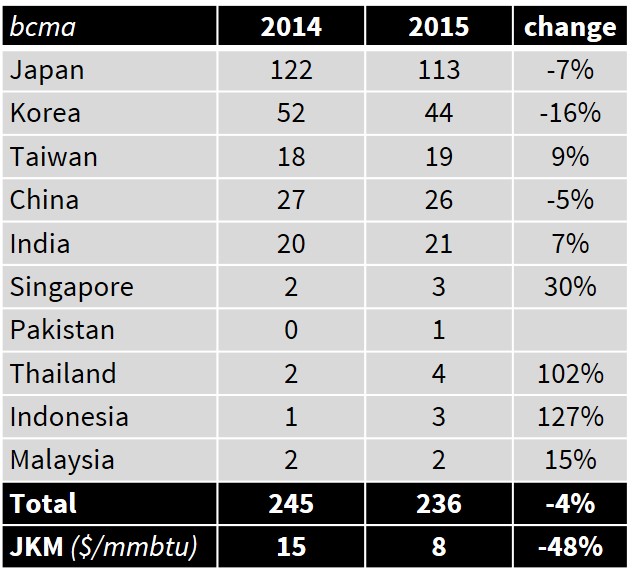

In theory Asian buyers should also be able to respond to falling LNG prices by increasing import demand volumes. But the practical evidence of this is so far limited. Despite a 50% fall in Asian LNG spot prices from 2014 to 2015, Asian LNG demand actually fell 4%.

Practical opportunities for physical substitution of gas for other fuels (e.g. coal and oil) are relatively limited. Some markets also face regas import capacity constraints. But most importantly, demand response is hampered by a lack of transparent market price signal mechanisms to induce the purchase of higher LNG volumes.

Asian LNG purchasing strategies tend to be driven by national policy and domestic portfolio considerations, in markets that consist largely of captive end users. Under these conditions the emergence of LNG demand response to lower prices is likely to have both a gradual and a limited impact in clearing the LNG glut.

Australian LNG exports shut in:

There is some speculation that low spot prices may induce a reduction in export volumes from the three Queensland liquefaction terminals (QCLNG, APLNG, GLNG) that have been developed based on coal bed methane feedgas. The logic here is that exports are uneconomic if netback spot prices don’t cover feedgas costs.

The most vulnerable of the three projects to export volume reductions is the Santos GLNG terminal given a shortage of feed gas relative to export capacity. If Santos needs to purchase incremental feedgas, it has a clear cost base against which exports may be reduced. But in practice this volume is relatively small and may not exceed the level of long term contract cover (around 85%).

In our view Australian exports under long term contract which are backed off by coal bed methane feedgas resource are less likely to be shut in. Coal bed methane production cost signals are relatively complex. There is also an environmental angle to ramping down production given a powerful domestic anti-fracking lobby (led by the agricultural sector). These factors suggest to us that disruptions to targetted production levels are likely to be limited.

US LNG exports shut in:

The US is a different story to Australia. The cost base of LNG terminal feedgas is driven by a liquid and transparent price signal in the form of Henry Hub. LNG export contract structures are also highly flexible in their ability to respond to price signals.

As long as netback spot prices cover the variable costs of Henry Hub, liquefaction and transport, LNG will flow out of the US. But if netback spot prices (e.g. in Europe & Asia) fall below this hurdle then US LNG will be shut in. US shut ins are likely to be highly price responsive i.e. within a 1 $/mmbtu range in netback spot prices, there could be upwards of 80 bcma of shut in volume response by 2020.

As a result, we view US shut ins as the backstop global clearing mechanism for the evolving LNG supply glut. In other words it is US LNG flexibility that can provide whatever additional volume response is required over and above the other three clearing mechanisms.

How do clearing mechanisms interact to clear the glut

The scenario we set out above shows an LNG supply glut of 68 bcma (49 mtpa) evolving by 2019 as new liquefaction capacity outpaces demand growth. Of the four sources of incremental volume response, we anticipate European power sector switching and US shut ins interacting to play the most important role.

US shut ins are likely to play a particularly important role as the marginal clearing response mechanism in the global market given their sensitivity to price signals. If the supply glut turns out to be less severe than we show in the scenario, then a lower volume of US LNG shut ins is required. If the glut is more substantial, then higher volumes of US shut ins are needed to make way for less flexible supply sources. This balancing role of US export flows significantly increases the importance of Henry Hub in driving global gas pricing dynamics (something we come back to next week).

It is our view that the current LNG glut is more of a 5 year than a 10 year phenomenon. There are important structural factors eroding the LNG surplus, as well as the market response mechanisms we describe above. These include declining European production, emerging Asian demand growth and the current hiatus of investment in new supply.

There is currently a strong industry focus on the immediate issues of a deepening supply glut. But rebalancing and recovery may not be that far out of sight, particularly given a 5+ year lead time to develop new LNG supply.

So how does the path to recovery look? What happens to global gas prices as the market rebalances? What are the implications for portfolio exposures and the gas investment cycle? These are questions we address next week as we look beyond the current glut at the three phases of market recovery.

Article written by David Stokes, Olly Spinks and Howard Rogers

| Client briefing pack

Timera Energy has published a client briefing pack ‘Global Gas Market – the path to market recovery‘. This includes an overview of current global pricing dynamics, how the LNG glut will be absorbed and the market evolution into next decade. You can download the briefing pack by clicking on the title link above or going to Our Publications. |

| Global LNG and European gas market workshop

Timera Energy offers tailored in-house workshops exploring the evolution of the global LNG and European gas market fundamentals, pricing dynamics and the implications for asset values and commercial strategies. These involve Timera Senior Advisor Howard Rogers (also Director of the Gas Programme at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies), who is acknowledged as a leading industry expert in the global gas market.

For more information please contact Olly Spinks. |