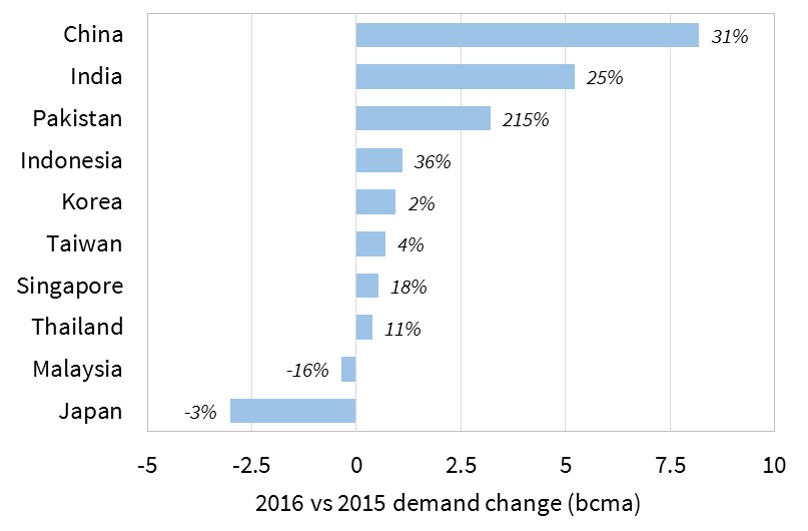

Global LNG spot prices have been relatively subdued over the past two winters. Increases in global liquefaction capacity and weaker demand have kept regional LNG prices within a relatively tight range of European hub price support.

But LNG spot price volatility is back this winter. Asian spot prices surged from just above 7 $/mmbtu at the start of December towards 10 $/mmbtu in early January. This opened up a significant premium over North-West European hub prices, signalling Asia’s requirement for incremental cargoes.

Early January then saw Southern European spot prices trumping Asia as a cold snap hit the Mediterranean. Pipeline bottlenecks within France caused a sharp price separation between Northern European hubs and their LNG dependent Southern neighbours.

The events of Winter 2016-17 make an interesting case study of how spot price volatility can temporarily disrupt structural global price convergence, despite prevailing supply glut conditions.

Asian LNG premium makes a comeback

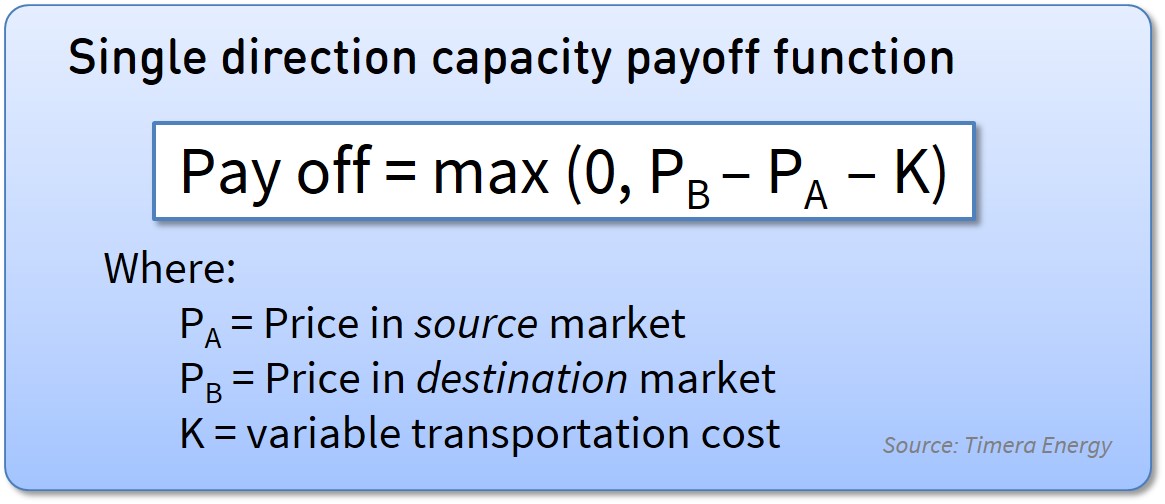

European hub prices have been the primary driver of spot LNG prices since the global supply glut took hold in Summer 2014. This is because North-West European hubs represent a liquid backstop in an oversupplied LNG market. If regional spot prices start to diverge from European hub prices, flexible LNG is diverted away from Europe to higher priced markets, checking the extent of regional price separation.

However the ‘gravitational’ effect of European hubs can break down over a shorter term horizon. This is because volumes of flexible LNG still make up a relatively small portion of the total market. LNG supply chain lead times also create practical constraints in moving gas between regions.

As a result of these factors, short term supply can be relatively unresponsive to spot prices (i.e. inelastic). The events of the current winter illustrate this dynamic.

Asian spot prices entered this winter at a relatively narrow premium to North-West European hub prices (~ 1 $/mmbtu). Over the first two weeks of December, a surge in Asian spot prices saw this premium quickly rise towards 4 $/mmbtu.

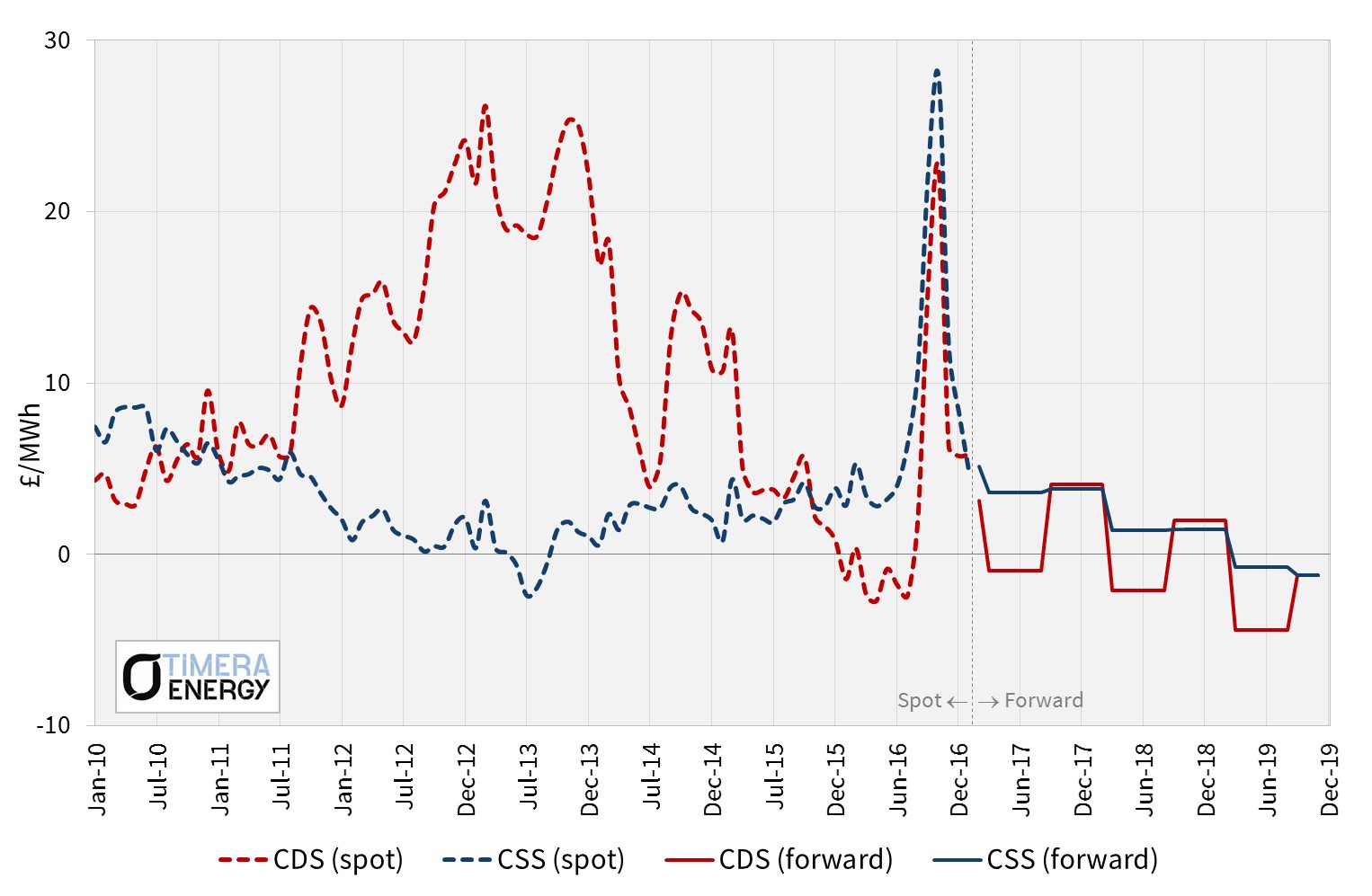

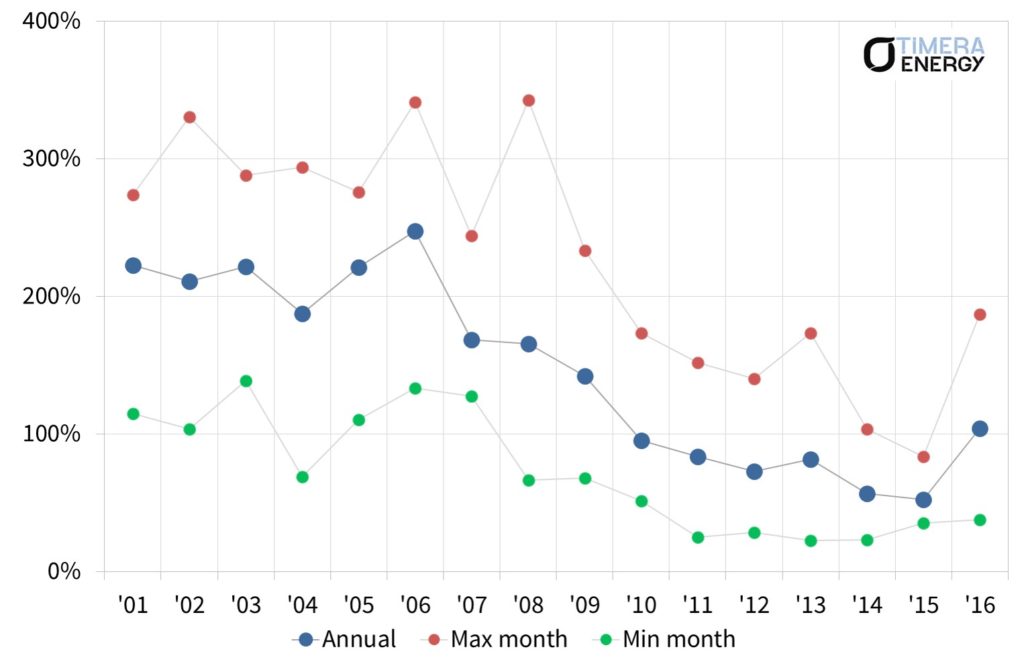

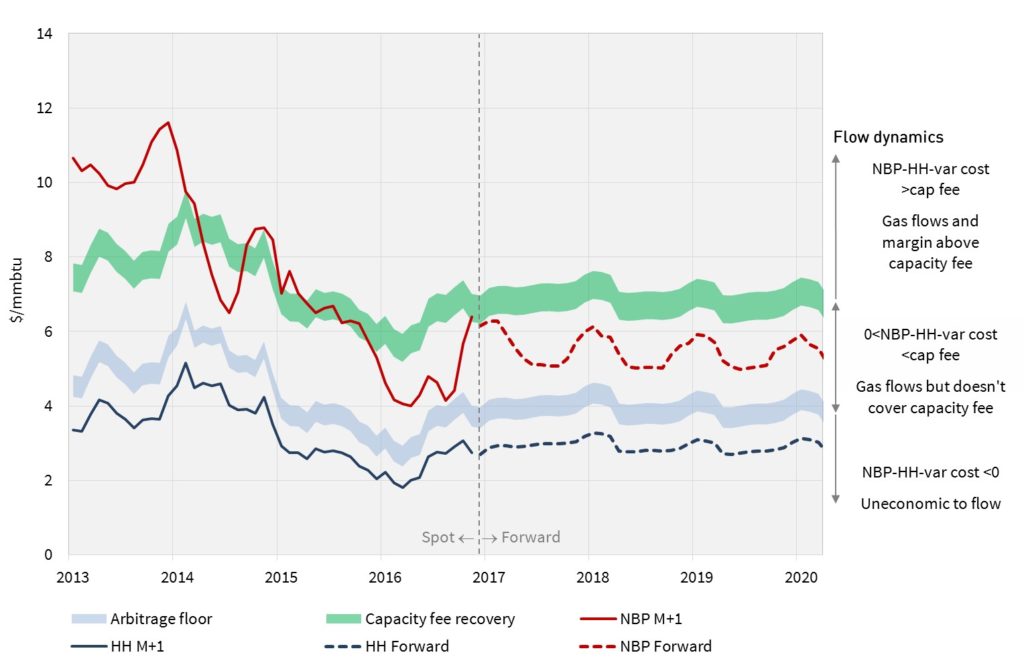

Chart 1 shows the evolution of prices in Asia versus European hubs in Q4 2016, relative to recent history. We have used Singapore Exchange (SGX) spot price data to show Asian spot LNG benchmarks (the Singapore and North Asia indices).

Chart 1: Asian spot vs European hub prices

Source: Timera Energy (data from LEBA/SGX)

Several factors contributed to the sudden tightening in Asia in Q4. On the supply side, the large Western Australian Gorgon project announced an outage at the end of November, compounding supply reductions from outages at an APLNG train in Queensland and the terminal in Angola.

At the same time, Asian demand for spot cargoes increased. South Korea faced several nuclear outages requiring LNG backup and Chinese demand was strong as the winter took hold. This surge in demand was suddenly pushing up a steep and contracting supply curve.

Southern Europe prices up to Asia

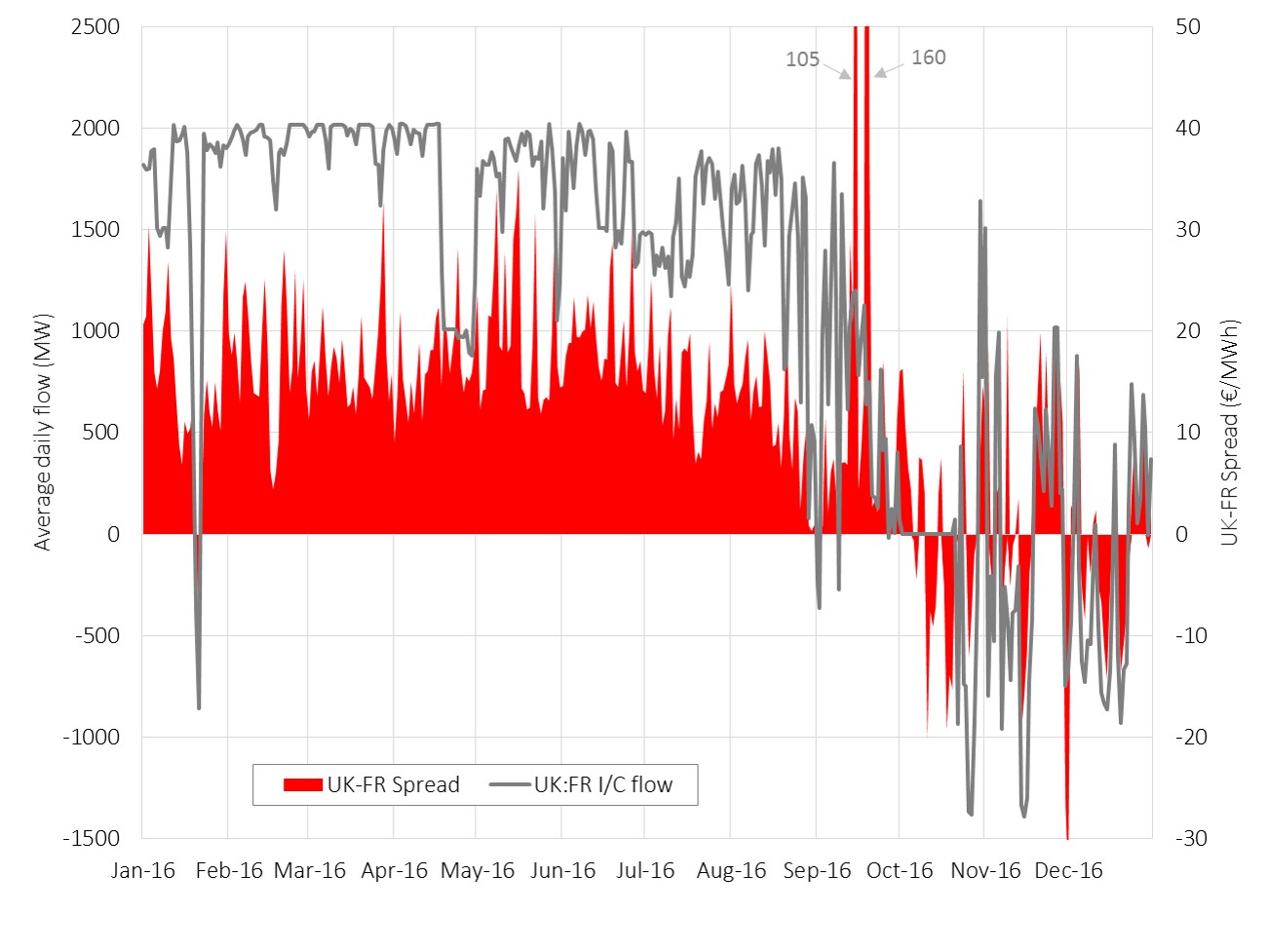

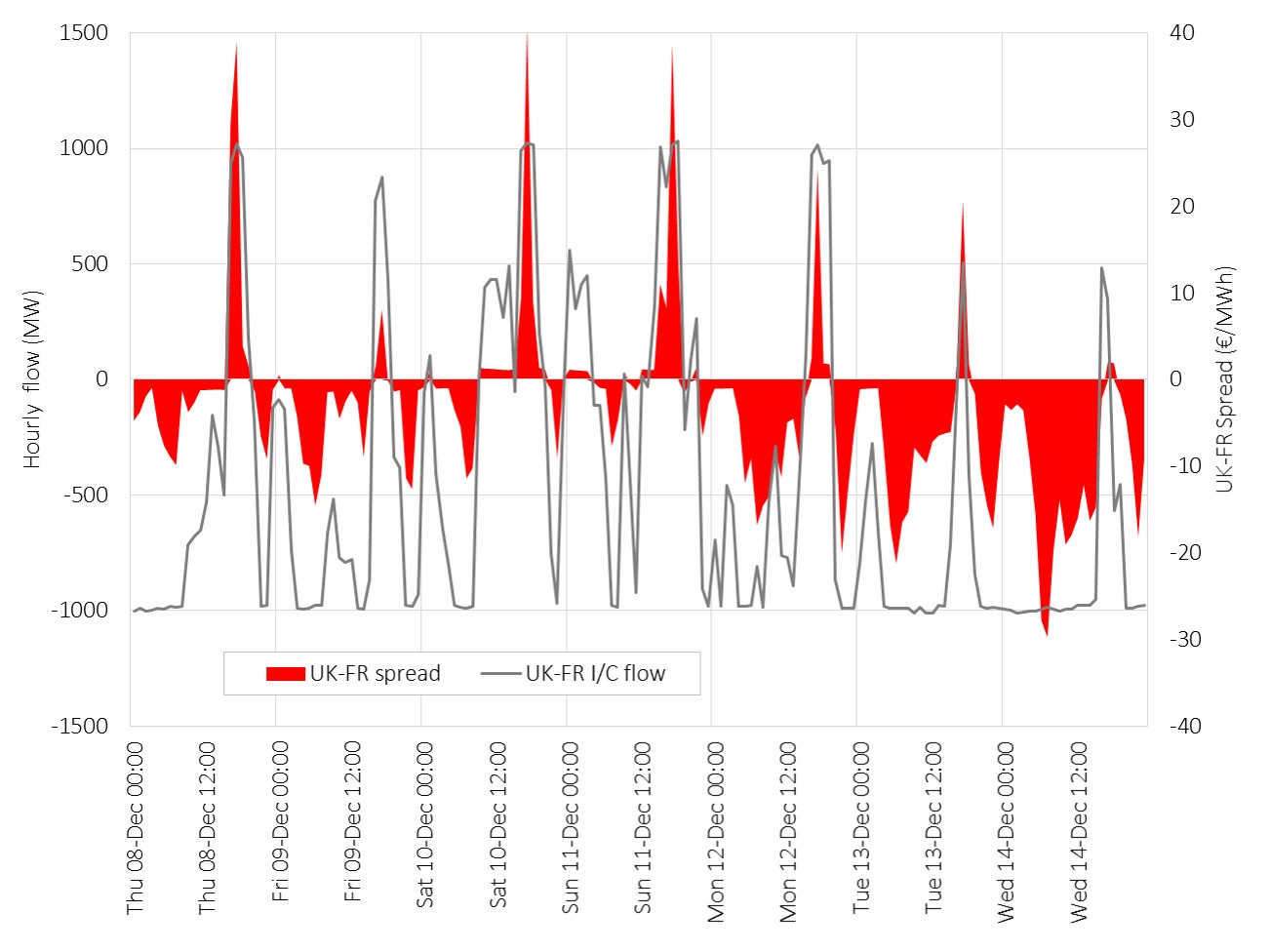

Gas flows within France are constrained by a North-South pipeline bottleneck as we have described previously. This can leave the TRS hub (an amalgamation of the former PEG Sud & TIGF hubs) in Southern France dependent on LNG imports to the Fos terminals on the Mediterranean coast in periods of higher winter demand.

Just as Asia sent a strong spot price signal to Europe to divert flexible LNG cargoes, Southern Europe had its own supply crunch. A cold snap hit Mediterranean Europe in early January with gas demand surging. This led to a shortage of cargoes available for Mediterranean delivery, exacerbated by an Algerian liquefaction terminal maintenance outage.

Relatively small price increases are typically required for Southern France to attract cargoes from other Mediterranean terminals e.g. in Spain. But a more widespread LNG shortfall in January saw Southern European spot price benchmarks surge through 10 $/mmbtu to open up a premium to Asia as can be seen in Chart 1.

Price separation of this magnitude between Northern and Southern Europe is typically a short lived phenomena. TRS prices can be seen re-converging with by late January as LNG imports returned. The key North-South pipeline bottleneck is also in the process of being alleviated with new pipeline capacity due to come online for winter 2018-19.

How is this volatility possible with a supply glut?

Price spikes and Asian spot premiums appear to be strange conditions for a structurally oversupplied global market. Are they evidence of a premature end to the global supply glut? And is global price convergence an over-hyped phenomena? Not in our view.

Spot prices re-converged with European hub prices in late January just as fast as they rose in early December. As a result, the premium of Asian spot prices over North-West Europe has fallen back to less than 1 $/mmbtu, signalling a return of surplus cargoes into Europe. The primary drivers of this ‘return to normal’ are:

- Winter demand surges reverting to normal

- Liquefaction capacity returning from outages

- LNG supply chain response to spot price signals

In other words the spot price volatility observed over December and January is a function of short term dislocations in supply and demand, and the supply chain response time required to rectify these.

Volatility events such as those observed over the current winter become less common in an oversupplied global gas market. But this sort of shorter term price volatility is inherent to the LNG market. The appearance of shorter term bouts of regional price volatility does not challenge the prevailing conditions of structural oversupply and price convergence between Asia and Europe.

We return next week to take a closer look at European gas market dynamics, Russian market share and gas coal switching.

Article written by Olly Spinks & David Stokes