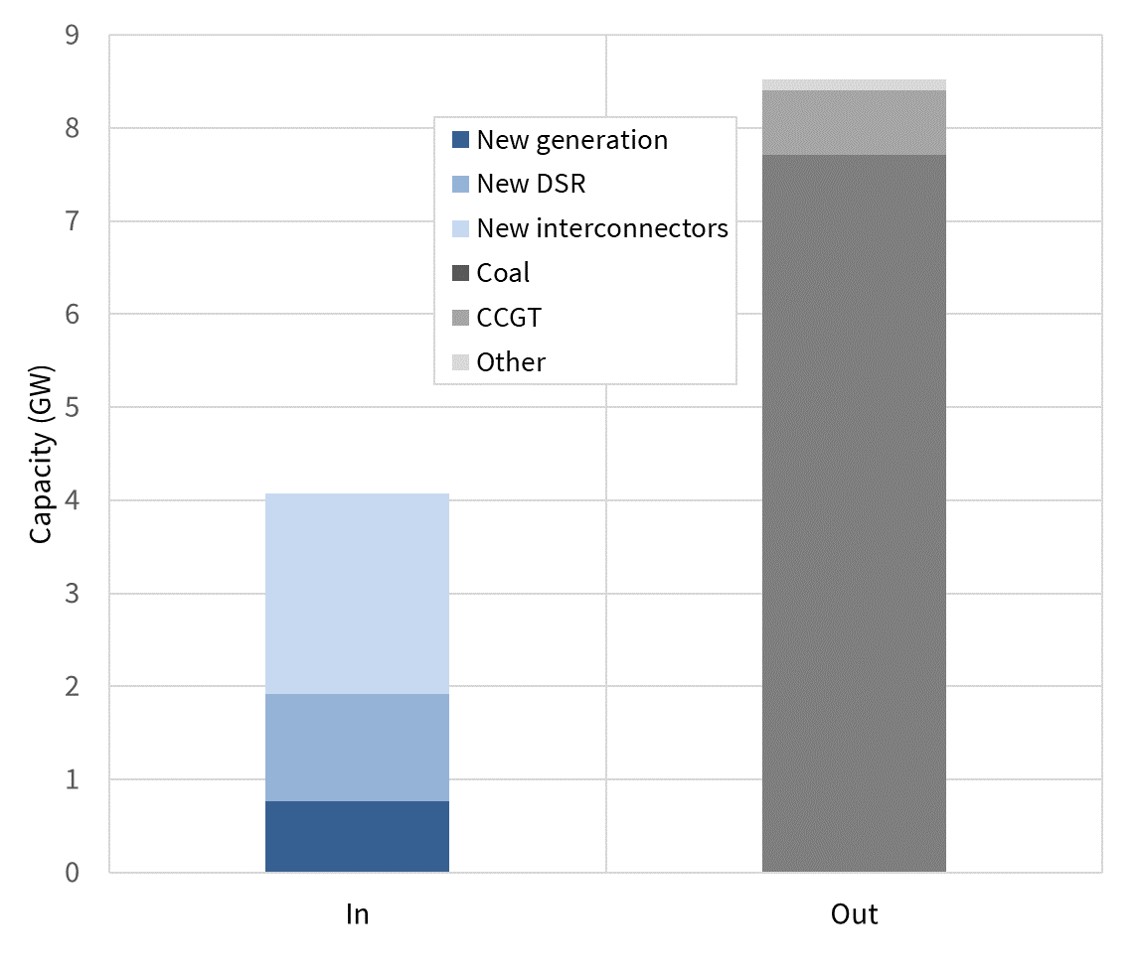

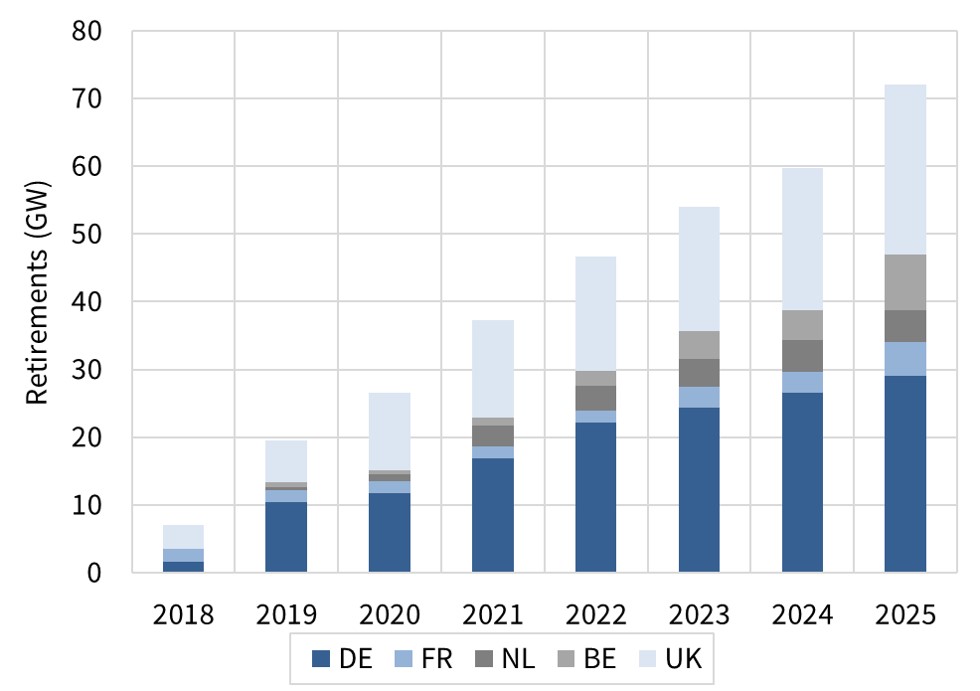

European power markets are facing a demographic issue. Flexible thermal generation capacity is ageing at a faster rate than it is being replaced.

This phenomenon is consistent with the intentions of policy makers as Europe moves towards decarbonization of the power sector. Thermal capacity is steadily being replaced by investment in renewable generation assets.

But new capacity is strongly skewed towards low variable cost and relatively inflexible wind & solar generation. This means the flexibility of remaining thermal power plants is playing an increasingly important role in ensuring power system security of supply.

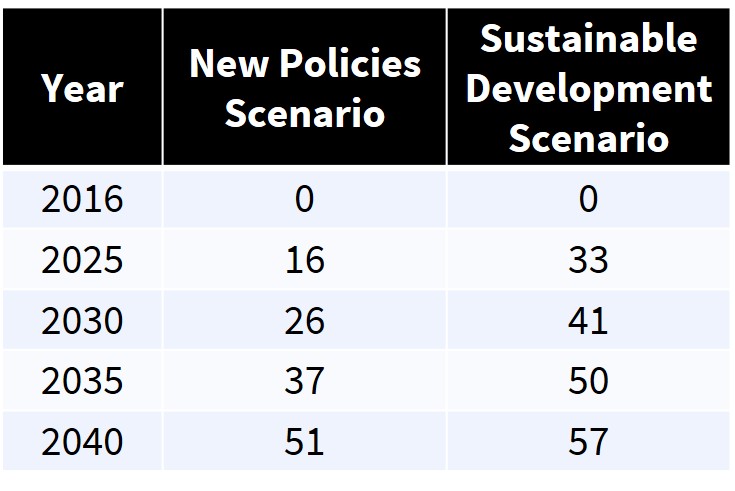

Low carbon sources of flexibility such as load shifting storage & demand side response are evolving quickly. But evolution of technologies, cost curves and policy support for these low carbon flex sources means that even under optimistic scenarios, Europe will rely on thermal generation flexibility well into the 2030s.

This means that European power markets face a balancing act over the next decade as they progress towards decarbonization. Part of this equation is about investment in new flexible capacity including new low carbon technologies. But capacity demographics are as much about plant deaths as about plant births.

In this context, we focus our next two articles on plant closures. Today we look at economic and other drivers of owners’ decisions to close plants. Then next week we set out a structured investment framework for assessing plant closure decisions.

Closure is more complex than just profitability

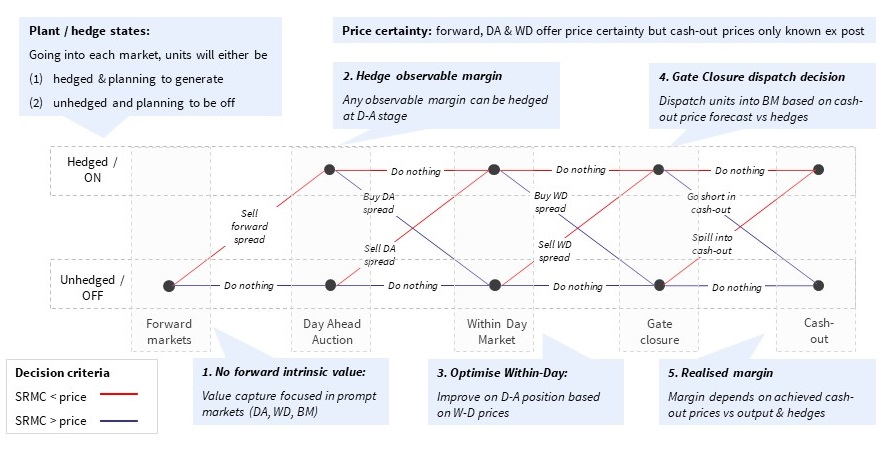

Simple investment logic points to plant closure decisions based on profitability. But it is important that profit is viewed from an economic rather than an accounting perspective. By this we mean making decisions based on opportunity costs.

All sunk costs should be excluded from the decision to close a plant. Closure economics should be based on an evaluation of avoidable costs. This is often not straightforward. For example in the context of a UK capacity auction cycle, more costs are avoidable four years ahead of delivery (T-4) compared to one-year ahead (T-1).

All other things being equal, these avoidable costs need to be covered by an adequate level of risk-adjusted revenue, to justify keeping the plant open. Although this concept seems simple, there is usually a complex interaction across a number of value drivers behind it. We summarise these in Table 1.

Table 1: Value drivers of plant closure

| Driver | Description | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Margin uncertainty | Uncertain evolution of wholesale, capacity & balancing/ancillary margins |

|

| Sunk costs | Defining which costs are truly avoidable by closing plant |

|

| Cost uncertainty | Elements of cost evolution can carry uncertainty |

|

| Cost reductions | May be options to reduce some plant costs |

|

| Decomissioning costs | Timing of incurring decommissioning costs can be a significant economic driver |

|

| Alternative options | Closure economics need to be consistently assessed against alternatives |

|

| Other risks | Performance of ageing assets needs to be appropriately risked |

|

Source: Timera Energy

Closure timing and triggers

The precise timing of a closure decision can often be triggered by major cashflow related events that impact the plant. An example of this in a UK, French or Italian market context is exit from a capacity auction (given associated loss of capacity revenue). Other events that can trigger closure include cashflows related to major overhauls, debt repayments and the need to meet changing environmental legislations (e.g. IED capex decisions on coal & lignite plants in Germany).

There can be important practical implications of decommissioning cost liabilities. For example tax and accounting treatment of balance-sheet decommissioning provisions can influence optimization of closure timing. So can the extent to which decommissioning provisions differ from estimated decommissioning costs. Regulatory risk around decommissioning costs is also a consideration, with decommissioning & clean up obligations typically becoming more onerous over time, typically favouring earlier closure.

Closure decisions can also be impacted by codependence with other units on the same site or in the same portfolio. For example, by closing one unit at a four-unit station it is unlikely that a quarter of fixed costs will be saved. Instead, fixed costs are spread over a smaller base and look more expensive from a CFO’s perspective. This may set the bells ringing for the remaining units.

Why decisions can deviate from plant economics

There may be rational explanations for plant closure decisions to deviate from those implied by a purely economic assessment. A good example of this is the portfolio effects of closure. From a strategic bidding perspective in the UK capacity market, portfolio players mays consider the impact of marginal closure decisions of certain plants on the rest of their portfolio. Portfolio value impacts may be driven by the clearing price on the remainder of portfolio generation assets or on costs passed through to integrated retail businesses.

There may also be behavioural or other factors in play that are not obvious from an external economic assessment e.g.

- Self-fulfilling prophecy: as closure looms, owners have a tendency to cancel/defer discretionary maintenance, often pushing the plant down an irrecoverable path to closure

- Grasping at straws: working in the opposite direction, owners can clutch for excuses to keep a plant (& associated options) alive, even if economics point to closure

- Recent acquisition bias: A recent acquirer of a plant may be anchored to pre-acquisition assumptions on market & margin evolution

- Last man standing: ‘If everyone else closes first my plant’s value will recover’, or a blind hope variation ‘something will turn up to save us’

- Broader perspective Boards can often be reluctant to make politically sensitive or reputationally sensitive decisions around plant closures

- Turkey voting for Christmas: a management team working with a portfolio of one plant may not make the same recommendations as a manager with a portfolio of a dozen units

Whether the drivers of closure decisions are economically rational, behaviorally rational or otherwise, these factors all have an important practical impact on plant closure timing. But that does not mean owners should step away from a structured economic assessment of closure decisions.

Large sums of money can be made or lost in optimizing the options associated with a thermal asset approaching the end of its life. We set out an investment decision framework for the assessment of closure vs alternative options in next week’s article, including a practical case study for CCGT assets.

| Timera is recruiting power analysts We are looking for a Senior Power Analyst and a Power Analyst with strong industry experience. Very competitive & flexible packages. Further details at Working with Timera. |

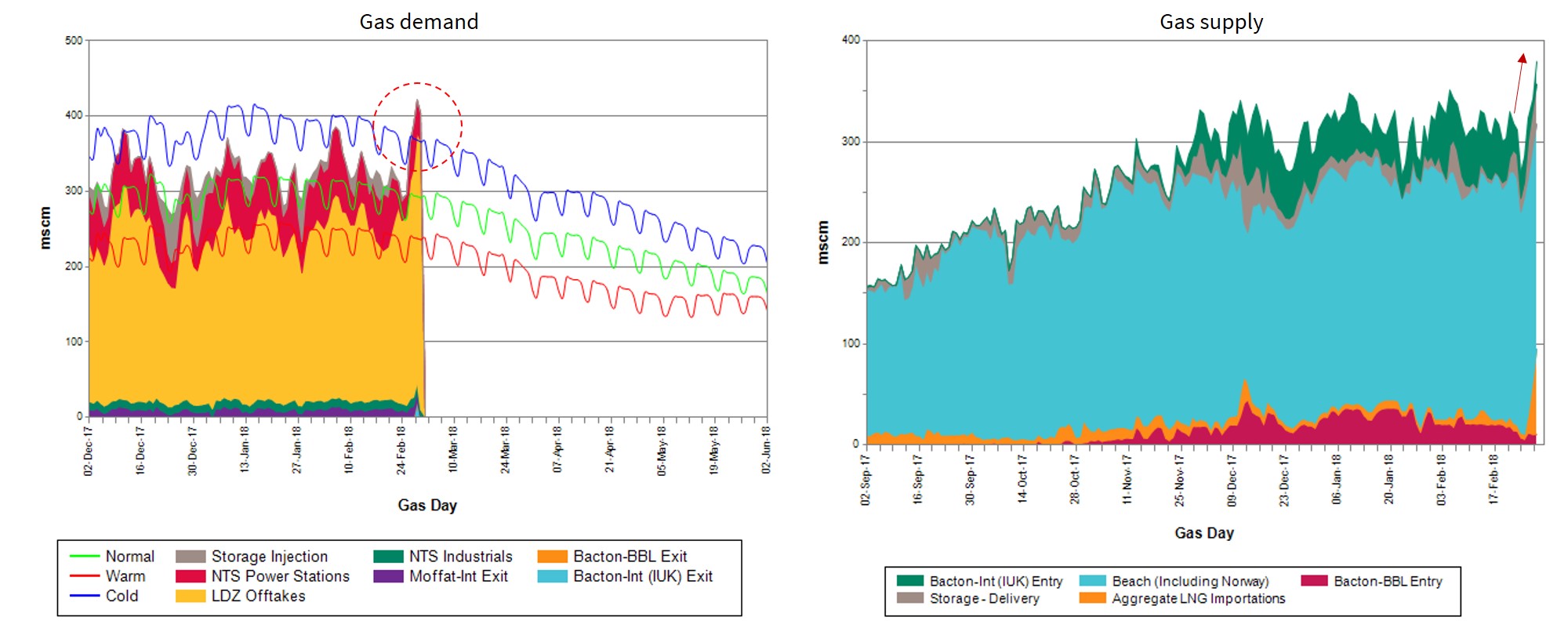

Source: National Grid

Source: National Grid