Welcome back to our first feature article for 2019. As has become tradition we start the year with five surprises to watch for on your radar screens. Usual caveat: these are not forecasts or predictions but cover areas were we think it is worth challenging prevailing market consensus.

1.UK capacity payments reinstated

The sudden suspension of the UK capacity market was one of the major surprises of 2018. It has left many asset owners with gaping holes in their business plans, in some cases resulting in an inability to cover fixed costs.

The UK government was caught completely off guard by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruling. BEIS (the government department responsible) has been scrambling to reassure capacity owners that the situation is under control. But industry confidence is understandably low given the scale of uncertainty set against a chaotic backdrop of Brexit politics.

Given these conditions, it is easy to build a ‘train wreck’ scenario. BEIS is pushing plans for an extra T-1 auction to cover next winter, but the timelines & complexity of delivering that solution appear to be uncomfortably optimistic. Adding to confusion is a lack of clarity as to (i) whether previous capacity payments may be recovered or (ii) what capacity owners and investors will face beyond next winter.

Wouldn’t it be surprise is some form of common sense prevails, even if initially via a messier ‘stop gap’ solution. The capacity market has underpinned security of supply in the UK. The ECJ ruling may accelerate some market reforms that were already underway, but it is very unlikely that it will derail the capacity market.

BEIS appears to be aware of the urgency to reinstate some form of capacity payments before next winter in order to avoid accelerated asset closures. They are also looking at solutions that could ‘backfill’ halted payments. Ultimately, some form of reserve mechanism payments via Grid (the TSO) could provide an initial emergency backstop. Our first surprise for the year is that the issue of capacity payment reinstatement is substantively resolved in 2019.

2. Merchant battery investment takes off

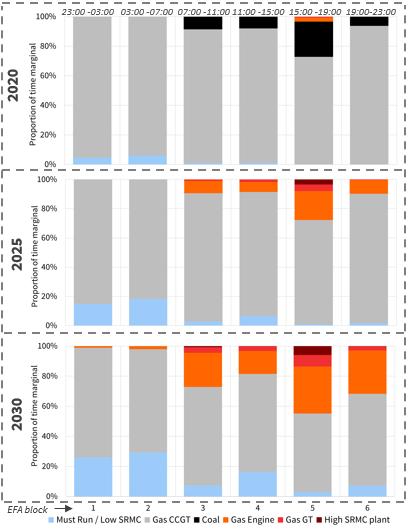

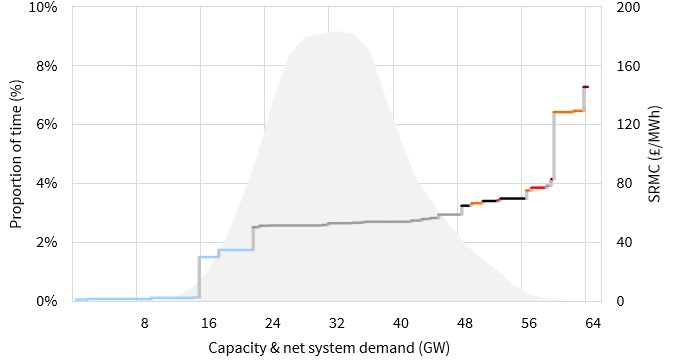

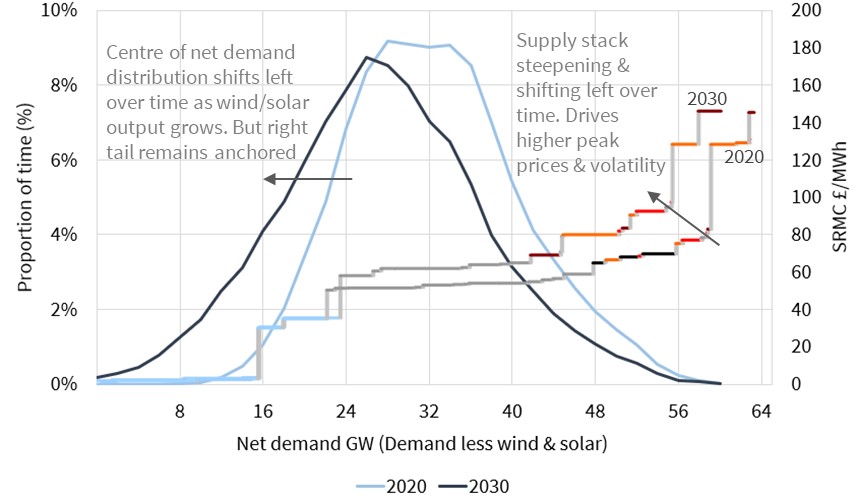

Battery storage projects to date have been underpinned by ancillary services revenues, particularly for frequency response. But this business model is being rapidly undermined by falling ancillary services revenues. Over the last two years, frequency response prices have plunged in both the UK and Germany (Europe’s two leading markets for battery deployment). This is forcing battery developers to change tack and focus on merchant revenue models Mafia Casino Online.

The merchant business model for batteries is a very different proposition. Most value is captured very close to delivery, by optimising battery flexibility from the day-ahead stage through to real time balancing. This means that owners and investors need to bear substantial market risk, relying on projections of extrinsic revenue to support investment decisions. We recently set out some of the challenges facing merchant battery investors.

Despite the headwinds described above, the pick up in investment momentum behind merchant battery projects may be a surprise in 2019. Developers are focusing on short duration lithium batteries where cost declines are currently fastest. There also appears to be strong investor interest in the scaling potential of merchant batteries despite the associated market risk. What has been missing to date has been a clear track record of bankable projects. That could change this year.

3. Gas demand shock

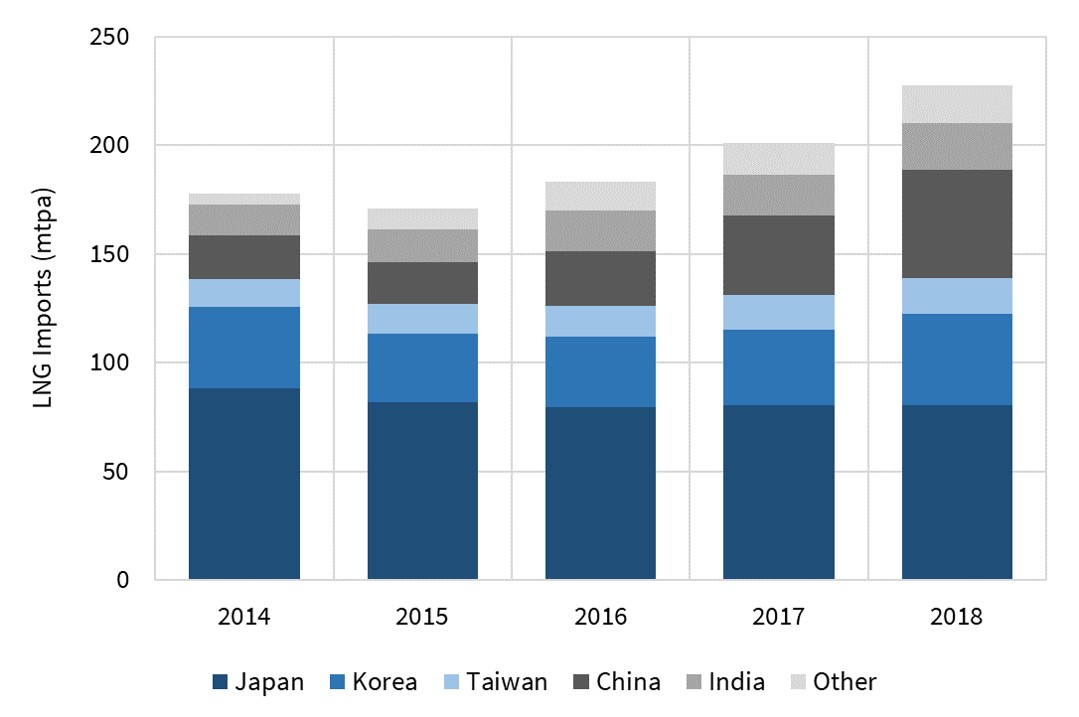

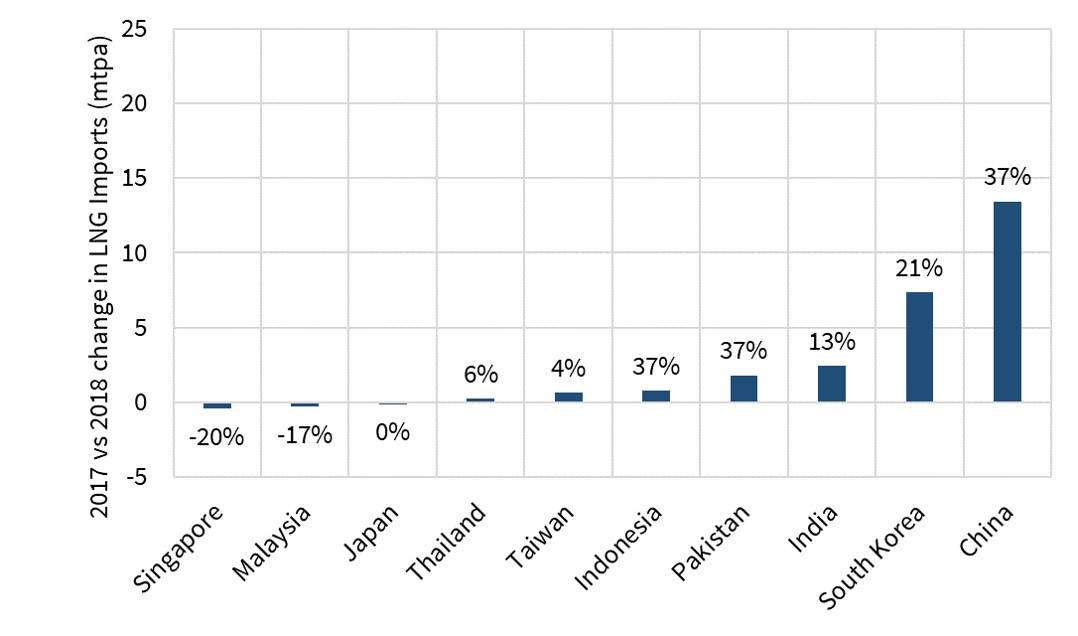

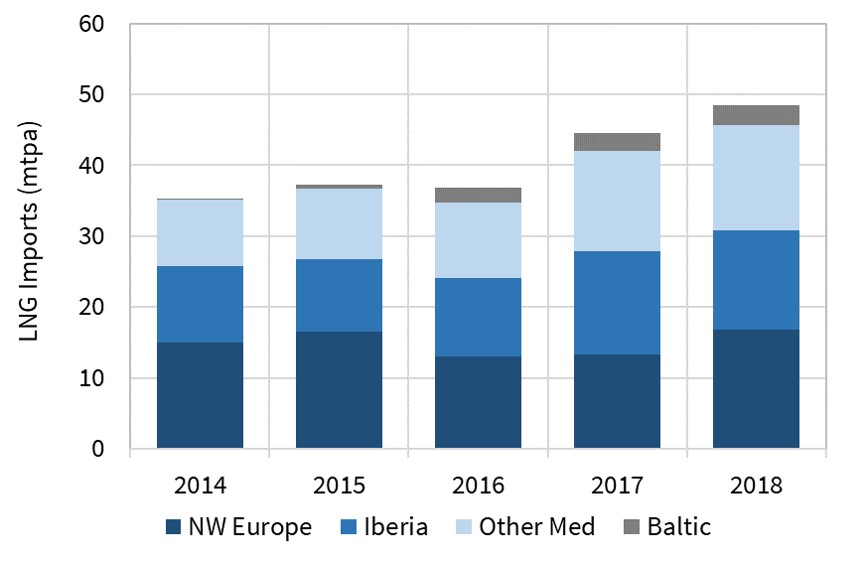

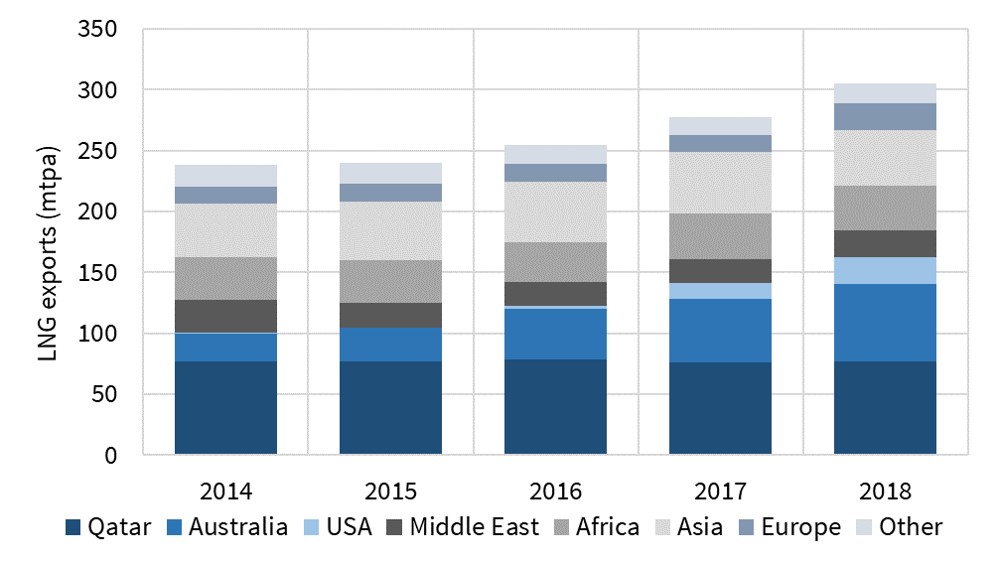

Global LNG demand has had a strong run since 2016, underpinned by Chinese annual demand growth of around 40%. European gas demand has also recovered significantly over the last 3 years, helped by stronger economic growth and power sector demand.

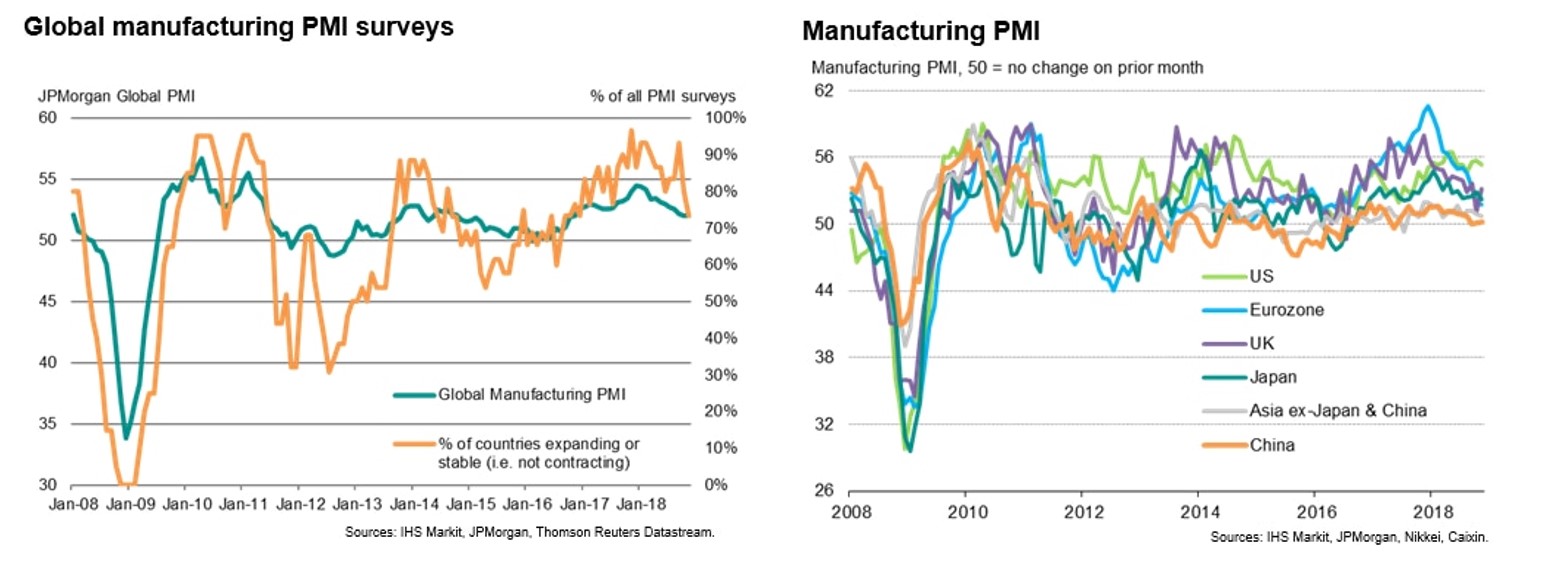

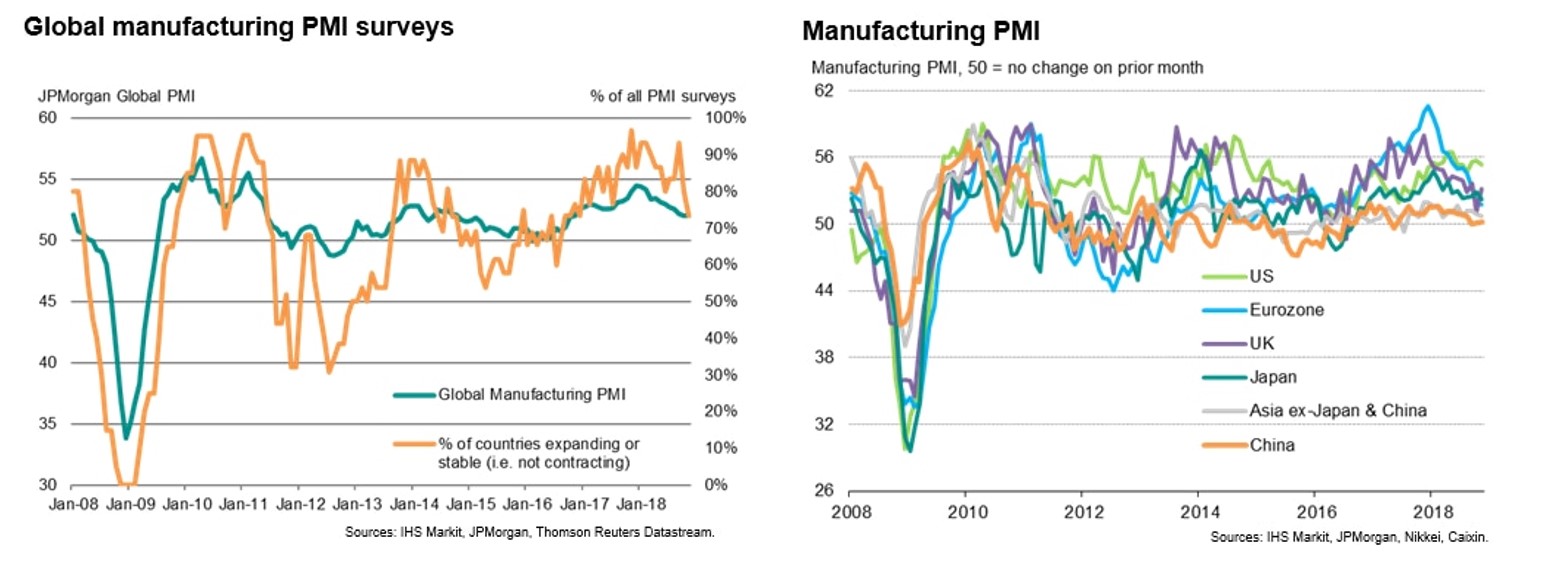

Global gas demand growth was driven by buoyant economic conditions across 2016-17, tagged by economists as ‘synchronised global growth’. As 2018 drew to a close this had transitioned to ‘synchronised global slowdown’. The 2018 slowing of growth in Chinese and European manufacturing data (as shown in Chart 1) is a particularly important warning sign for global gas demand.

The global economy is now entering its 11th year of consecutive economic expansion since the financial crisis. An expansion of this length is unprecedented in modern times. It raises the risk of a sharper slowdown or recession in 2019. Sharp declines in oil prices and global stockmarkets in Q4 2018 are flagging the risk of a weaker economic outlook.

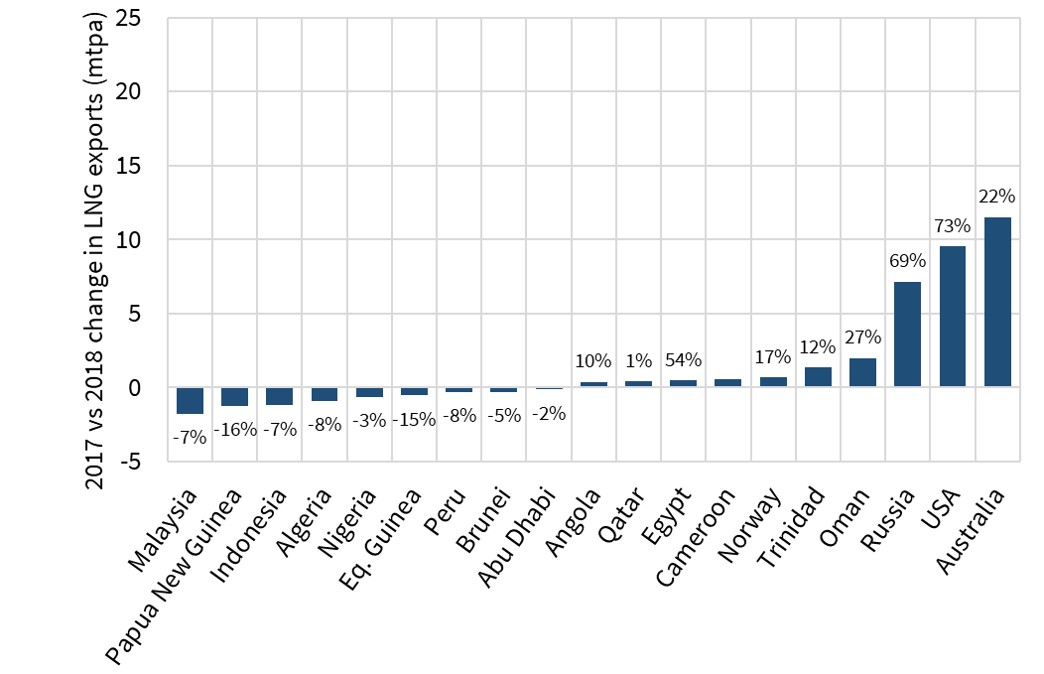

Strong gas demand in Asia & Europe has seen large volumes of new LNG supply absorbed with relative comfort across 2016-18. This has diminished the risk of a prolonged supply glut. But a gas demand shock in 2019 would come at a time when the largest volumes of the current wave of new LNG supply are coming onto the market.

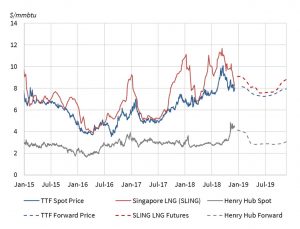

Gas prices surprised to the upside in 2018. But a major demand shock in 2019 could cause a temporary slump in TTF & Asian spot prices, particularly if accompanied by falling coal & carbon prices dragging down power sector switching levels.

Chart 1: 2018 slowdown in Purchasing Manufacturing Index (PMI) data

4. Gas storage closures

A number of higher cost, less flexible European storage assets are in trouble. The funeral bells have been ringing for five years. Owners have been holding on in the hope of a market recovery, deferring maintenance and investment decisions in an attempt to keep carrying costs to a minimum. 2019 may be the year that a significant volume of storage capacity is finally pulled off line.

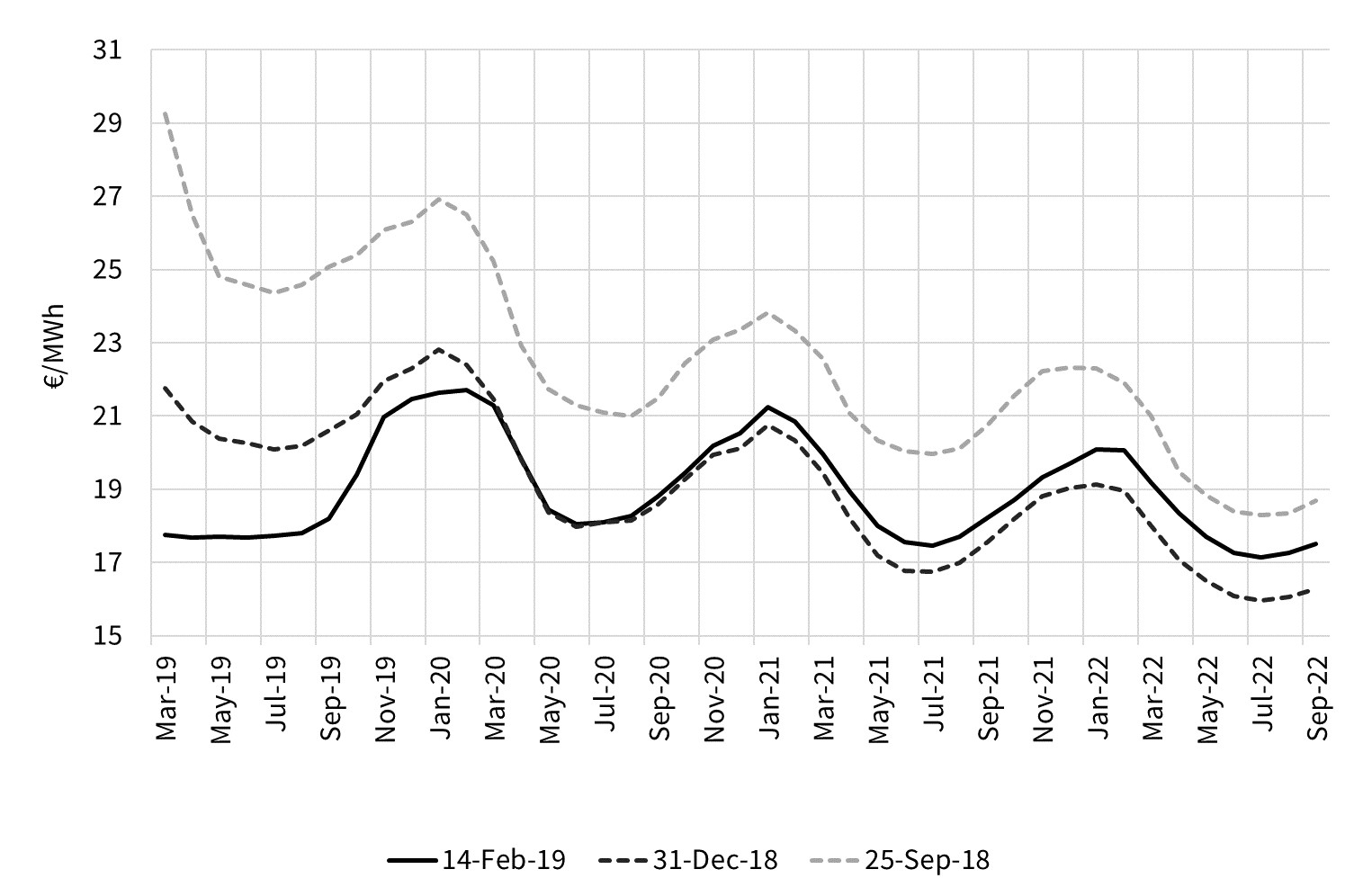

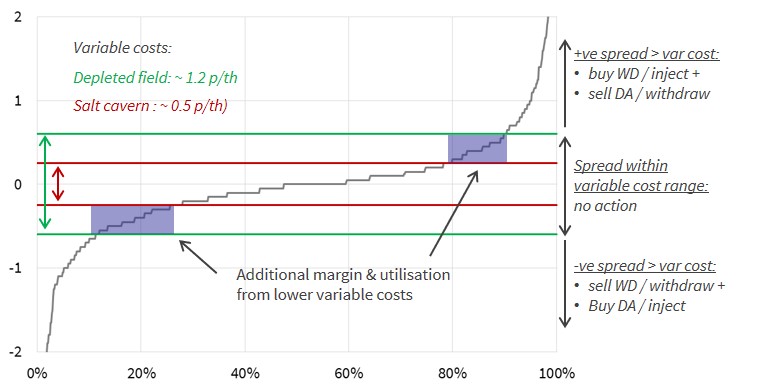

TTF seasonal price spreads have remained stubbornly stuck between 1-2 €/MWh for most of the last five years, barely covering the variable costs of cycling seasonal storage. Many asset owners have managed to hang on due to a combination of:

- Long term contracts at more favourable terms (many of which are now expiring)

- Hopes of a market recovery

- Hopes of regulatory reform to support storage (e.g. changes to system charges).

But owner patience may be running out, particularly those suffering negative cashflows. Storage assets with a higher fixed cost or variable cycling cost base are particularly vulnerable. Any requirement for substantial capex spend may be terminal. The precipitation of closure decisions if it happens in 2019, will likely contribute to the start of a more sustainable recovery in value of European gas supply flexibility.

5. Rising cost of capital

Energy infrastructure developers have benefited from an historically low cost and easy availability of capital over the last five years. Could that be about to change in 2019?

Easy access to capital has been underpinned by low borrowing costs. The cost of raising debt can be broken down into two components:

- Risk free rate: Massive central bank quantitative easing has driven down interest rates on ‘risk free’ government debt. This is most clearly reflected in 10 year German bond yields which are currently below 0.2%.

- Credit risk premium: The credit spread over risk free rates is also at low levels historically, reflecting e.g. low default rates and European Central Bank buying of corporate debt as part of its quantitative easing measures.

So what could change in 2019 to reverse 5 years of readily available capital targeting energy infrastructure? Firstly, global central banks are entering a phase of quantitative tightening in 2019 which could see borrowing rates rise. Secondly, the potential for a deterioration in economic conditions could widen credit spreads. Thirdly, investor risk appetite may decline as a result of the first two factors.

The impact of a higher costs of capital in European energy markets would be felt most by companies or projects with higher leverage. Higher cost of capital erodes asset margins via increasing debt servicing costs. It also increases the cost hurdle for investment in new infrastructure.

We wish you all the best in navigating these (and no doubt many other) surprises across 2019.