The COP-21 Paris climate accord marked the beginning of the end for coal in Europe. Most European countries are taking clear actions to drive coal out of the energy mix through the 2020s. Could gas face a similar future from the 2030s?

Gas asset owners and investors are increasingly focused on understanding this risk. While the role of gas in Europe may diminish from the 2030s, it is unlikely to disappear before the 2050s. But the tangible impacts of decarbonisation sit well within a gas asset investment horizon. This creates a requirement to understand, quantify and manage associated risks.

One of the key risk mitigation actions for the European gas industry is embracing new low carbon technology and ensuring there is appropriate policy support in place to deliver this. There are clear lessons here from the European power industry. Policy support for wind and solar has not only slashed the cost of deployment, it has created enormous growth opportunities for European energy companies in leading the global role out of renewable technologies.

Professor Jonathan Stern is Founder of the OIES Gas Research Programme. In a paper published in Feb-19 he sets out a vision for potential pathways and narratives to support decarbonisation of the European gas market (Narratives for Natural Gas in Decarbonising European Energy Markets). Over the next three weeks we publish a series drawing on material from Jonathan’s paper. We highly recommend his paper for further details.

In today’s article we focus on the risks that decarbonisation poses for energy companies and the potential options for decarbonising European gas markets. Then in next week’s article we explore the impacts of decarbonisation on the gas value chain and potential impact on different players.

Why the gas industry needs to take decarbonisation seriously

Governments in most of the largest European gas markets are genuinely committed to COP21 decarbonisation targets. Some future targets may be missed. But governments appear very unlikely to abandon their commitment to large scale decarbonisation by 2050, or to substantially delay its implementation.

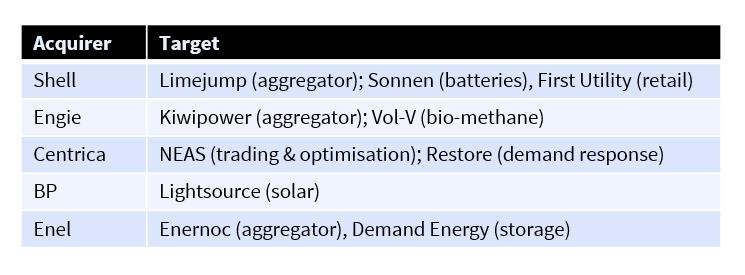

Importantly, a number of leading technology, energy and industrial companies are also swinging their support behind the push to decarbonise. Motives are no longer just focused on Corporate Social Responsibility. Momentum is increasingly being driven by a strong financial motivation to lead a seismic transformation in the way we source and use energy.

To ignore decarbonisation and delay action on the part of the gas industry, invites governments to decide that gas will not play a significant role in Europe’s long term energy future. This in turn increases the risk that there will be insufficient time to prepare for decarbonisation before unabated methane needs to be phased out.

The advocacy narrative of the European gas industry over the last decade has focused on coal to gas switching and backing up renewables. There is logic behind this approach. The reduction in US carbon emissions since 2007 demonstrates the benefits of power to gas switching. And gas-fired power is playing a structural flexibility role across European power markets.

But the ‘switching & backup’ narrative has failed to convince governments, NGOs, and a rising portion of media & the public that the role of gas can help achieve post-2030 decarbonisation targets. The gas industry therefore needs to develop a decarbonisation vision and associated narratives which effectively address the post-2030 period.

Technology options for decarbonising gas

There are a broad range of approaches and technologies that could be applied to reduce the carbon foot print of the European gas industry. These are grouped into four categories in Table 1 with a high level summary of pros and cons.

Table 1: Approaches for decarbonising gas

| Technology | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Power to hydrogen / methane |

|

|

| 2. Gas steam reforming to hydrogen (SMR) |

|

|

| 3. Bio & waste gas |

|

|

| 4. Methane Cracking |

|

|

Source: Timera Energy, drawing on Jonathan Stern’s paper referenced above.

1. Power to hydrogen / methane (P2G): This relies on the principle of electrolysis: to separate water into its component parts of hydrogen and oxygen. Experimental pilot plants were developed in the late 1990s and early 2000s. But potential for widespread commercial deployment has been supported by falling costs of renewable power generation and increasing periods of renewable ‘curtailment’ given excess supply.

Current progress of P2G technology suggests relatively small volume potential unless large amounts of low/zero cost renewable electricity is available, or dedicated off-grid renewable energy systems are built in regions with high wind and solar resources. The Ecofys (GfC) estimate of 24 bcm of renewable hydrogen from wind and solar power in 2050 is two and a half to five times higher than ENTSOG’s scenarios for 2040.

This technology might be adequate if the role of gas in the European energy mix is only to provide daily and seasonal back up for renewable energies. But to maintain anything close to the scale of the gas market today, biogas, biomethane, and power to gas would need to be supplemented with the reforming of methane into hydrogen accompanied by carbon capture, utilisation and storage CCUS.

2. Gas steam reforming to hydrogen options: Large scale methane reforming with carbon capture to produce hydrogen for network distribution to residential and commercial customers would be a completely new development. There are currently only two operational natural gas-based carbon capture projects in Europe. These are both at Norwegian gas fields (Sleipner and Snohvit) with CO2 injection directly into offshore reservoirs. There are however a range of other projects at the feasibility study or test stage in six other European countries.

At the moment, large scale methane reforming to hydrogen with CCS is under serious consideration only in the UK. In southern Europe there is greater emphasis on biogas and biomethane development. The emphasis on offshore structures is the result of onshore CO2 storage being considered politically difficult in major continental European gas markets due to environmental opposition.

There are strong logistical advantages to gas producers from reforming methane and producing hydrogen either at the field or where the gas is landed onshore. The advantage of such pre-combustion CCS would be that only offshore CO2 pipelines would be needed. The potential disadvantage is that all networks and customers in those regions would need to be converted to hydrogen.

3. Biogas/biomethane: The primary method of biogas production is the biological breakdown of organic material through anaerobic digestion. Biogas (containing CO2 and water vapour) can be upgraded to biomethane by a variety of methods (absorption, adsorbtion, methane filtration, and cryogenic separation) which can then be used interchangeably with natural gas. While this means incurring higher costs, it then facilitates use of biomethane with existing gas infrastructure (e.g. via blending).

The most optimistic of a range of forecasts (for Europe) sees the possibility of 98 bcm of biomethane from biomass sources by 2050.The Entsog scenarios for 2040 are very substantially lower, showing only 20-50 bcm of biomethane production in 2040. Even these more conservative estimates raise a major query over reliance on food crops given a shortage of appropriate waste.

Synthetic natural gas (SNG) can also be produced from gasification of waste via a thermo-chemical process using biomass and/or other waste as a feedstock. This technology is still at an early stage of development.

4. Methane cracking: An alternative method of hydrogen production is methane cracking which splits methane into hydrogen and a solid carbon residue (carbon black) which can then be used in a range of industrial processes. This could resolve some of the problems and costs of carbon storage, but the extent and scale of the utilisation options for carbon black are uncertain and large scale storage would still be required.

Russia is investing substantial resources in this technology as a potential means to support gas sales into Europe on a long term basis. This process is currently at the laboratory testing stage and it remains to be seen how quickly it will develop. But Russia has a very strong financial incentive to succeed given its vast natural gas resources & reliance on gas sales revenues.

Making it happen: time frames

Many European countries are aiming to largely decarbonise their power sectors by 2030. Focus then shifts to the heat sector across the two subsequent decades. So the time available to demonstrate that methane can be retained in the energy mix on a large scale beyond the next 20 years is relatively short.

Following this logic, it will not be possible to recover methane-related infrastructure investments requiring a longer depreciation period. This provides a very strong motivation for the gas industry to demonstrate that decarbonised gas options are realistic and cost-effective versus alternative low carbon options. Achieving this across the next 5 years is imperative in order to provide sufficient time for a large-scale gas network transition over the following 25 years up to 2050.

The pilot projects currently in operation will need to be followed relatively quickly by commercial scale projects in order to be operational by 2025. This in turn will require technical, regulatory, and financial frameworks to be in place to allow final investment decisions to be taken in the early 2020s. There are major uncertainties that need to be addressed in the next 5 years, of which the most immediate are technical and logistical difficulties and costs.

Making it happen: cost

A particularly important issue is the capability to ‘blend’ hydrogen into the existing gas network. This provides a market for hydrogen produced. But it also enables use of existing gas infrastructure, substantially lowering the time and cost hurdles for kick starting decarbonisation.

Hydrogen is already blended with methane in the Netherlands. Studies suggest that blending up to at least 20% hydrogen in gas supply may be possible. Blending of that volume could support a substantial scale of hydrogen production within existing gas networks in order to ramp up decarbonisation in the 2020s.

It is very difficult to make accurate cost estimates for the different decarbonisation options. Only biogas costs currently come close to European hub prices (e.g. a 15-30 €/MWh range), although this is without associated CCS. The lower estimates for biomethane, power to hydrogen and particularly power to methane costs range from €40-80/MWh while the higher estimates are €150-260/MWh.

Wind & solar demonstrate the potential for rapid cost declines as technologies scale with the appropriate policy support. That is why it is essential for the gas industry to launch commercial scale projects as soon as possible. The current reality is that large investments are required in projects that do not yet offer a commercial return.

The best way forward for the European gas industry is offence rather than defence. Decarbonisation presents as many opportunities as it does risks. But a clearer vision and policy framework is required to make it happen.

| May Mannes joins Timera as a Managing Director. See more details on May’s CV and background on Our Team page. |